There is a futility to championing ideas which, once derided, have now been vindicated by the zeitgeist, in the same way that the idea of seeking innermost truth against the illusory grain is easily written off as vain. Both definitions of vanity apply here: present order, if nothing more than the tumultuous outcome of past ones, sneers at the mortal efforts of singular souls to disrupt it, and these souls, in turn, cast themselves out, if only to envision some posthumous glory to call their own. Such describes the prickly notion of authorship, whether of words or of ideas. Its critics, from Barthes to Bitcoin, have time and again dismantled the singular consciousness at its center and vaunted their sprawling reams of context, while its defenders acclimatize to a blossoming vocabulary of self-reflexivity, or die trying. Or they mount the simplest defense of all — they write.

Writing this piece, ironically enough, proves challenging given that little defense is quite needed; the jury is off duty. For Leos Carax, a man of 64 years, the label of enfant terrible has somehow felt both prescient and overdue, ranging over a kinetic and electrifying body of work whose deconstructive impulses have always belied a horizon of desperate authenticity. Holy Motors and Annette, made nine years apart, propelled themselves by sheer re-invention, whether through the fervid tunes of song and rock opera or in the very act of shapeshifting and metamorphosis, while It’s Not Me, Carax’s 40-minute confessional, sought to articulate the filmmaker’s gnawing identity crisis via gentle, Godardian mimicry. If these works, literally and figuratively emplaced in the 21st century, continue to present a degree of controversy, they have, for better or worse, mellowed the critical dissensus from its hitherto virulent and reactionary form. Their predecessors, meanwhile, have more or less shaken off their difficult and contemptuous label for a more measured and respectable one.

This might be especially true — and not without irony — for Pola X, Carax’s thorny and utterly disquieting adaptation of Herman Melville for modernity adrift. Released at the turn of the millennium and after the troubled production of The Lovers on the Bridge (1991), the auteur’s fourth feature yields an anachronistic interpretation of fin de siècle aesthetics, set in contemporary France but rooted otherwise in premodern anxieties. Not for no reason does it begin with a show of dissonant force: Hamlet, proclaiming time out of joint, heralds footage of bombs torpedoed onto cemeteries, the destruction of two world wars paired with the funereal cacophony of late-period Scott Walker. Past this frantic scrambling arrives a scene of unadulterated serenity, in which the eponymous heir of Melville’s Pierre; or, The Ambiguities lounges in the family château, high off his anonymous success as a debut celebrity author. Pierre, played by the late Guillaume Depardieu (son of the great and notorious Gérard), is writing his second book, unsure of whether to endow its hero with the call of “recklessness,” or “imprudence,” or possibly “temerity.”

Synonyms attest to the breadth and beauty of language; in Pola X, they reflect boredom and disarray. Bored with his fiancée Lucie (Delphine Chuillot) yet consumed by some troubling omen of the imagination, Pierre entertains the bourgeois fictions of the rebellious aesthete, scooting across the countryside on a vintage bike, en route to what at first appears as an uneasy reunion between him, Lucie, and his cousin Thibault (Laurent Lucas). As if tiring of the potentially psychosexual dynamics in this trio, Carax forestalls their plotline with the more convenient arrival of Isabelle (Yekaterina Golubeva), the frazzled and mysterious woman who stalks both Pierre and his dreams. Her presence is not synonymous with anything; her explanation for it an immediate cause for him to end his old life and start anew. Isabelle, leading him into the nocturnal woods, alleges that she is his half-sister; their father, a disgraced diplomat of the ’70s, had conceived her while in the Balkans and, if she is to be believed, had her briefly stay in the château as a young girl. “I want nothing,” she tells Pierre, “but you believe me.”

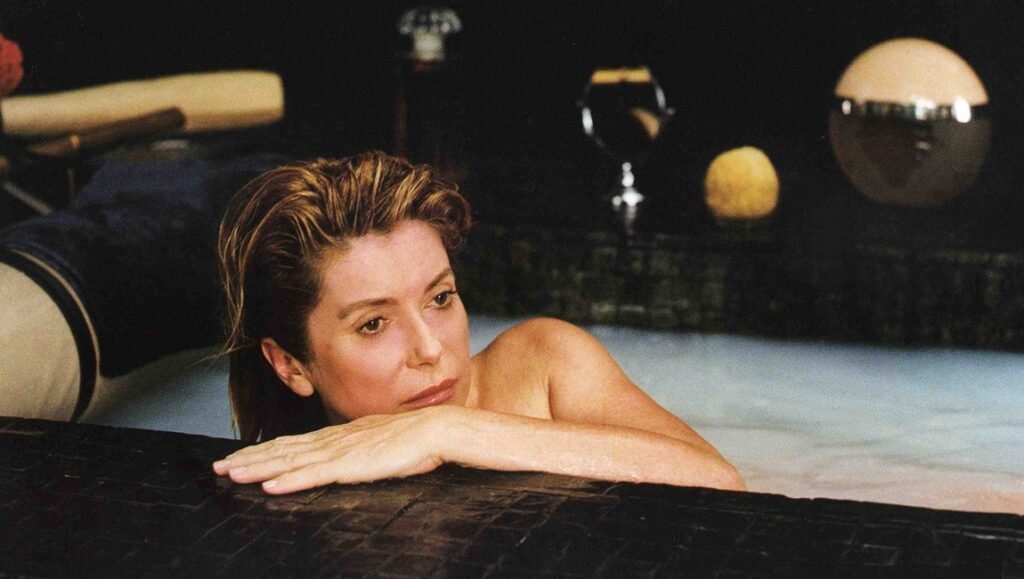

In both versions of Pola X released, this belief is substantiated with varying degrees of certainty. The more elliptical theatrical cut shows Pierre confronting his mother, Marie (Catherine Deneuve), and hacking away at a sealed-off attic to reveal Isabelle’s ostensible childhood bedroom, while the miniseries version appends significantly more footage, including a fantastical sequence in the room where Marie tacitly admits Isabelle’s existence to him. But Pierre’s convictions predate his flimsy confirmations, self-affirming in truth as they are truth-seeking in spirit. So begins his romance and Romantic descent — through the forests, through the night, through Paris, through poverty — unto an abnegation of lavish mediocrity and an absolution of the artistic soul. Leaving Marie (whom he addresses as “ma sœur”) and Lucie to grieve, while channeling an expression of purest commitment to free will, Pierre elopes with his half-sister, joined by her two companions Petruța and Mihaela, of Romanian, possibly Gypsy, blood. If respectable hotels won’t take them in, the disreputable margins of society will.

The intimacy between brother and sister that blooms within these margins is no less disturbing: they fuck amid pallid light and silence, consummating a hungry love made opaque by their separate desires. Hers is unknown — a partner? permanent residence? — while his is nothing less than his very individual. Like his American progenitor, Pierre looks for a comeback; not from self-imposed squalor, but from an unspoken wrongness and tedium. In Melville’s case, Moby Dick had been coolly received by critics, whereas Pierre (as his pseudonym “Aladin”) enjoys the bounty and banality of fame. And like his doomed protagonist, Carax pursues an obscure vision of the truth, perhaps more knowingly, perhaps in self-conscious jest. Pola X abounds with symbolism, but these are tricky signs. The vagrant entourage camp, briefly, at a “Hotel Ahab”; Pierre’s all-but-disclaimed first folio is titled In the Light; the three chapters in the miniseries version proceed along this line, from light to shadow and toward shadowy, sanguine death.

These are hardly surprising for a film whose title (the French abbreviation of Melville’s Pierre, plus “X” for the script’s tenth draft) and authorship (an anagram of Carax’s first and middle names) brim with elusive, postmodern ambiguity. Pierre has less recourse to innocence in this than Melville: his persona is fashioned from the graveyards of modern industrial capitalism, as much a product of opposition to his investor cousin as it is a reflection of the counter-cultural militant group he later lodges with. Carax, even less: having witnessed and cemented the rising New French Extremity movement, he serves both as Melville’s reader and as Pierre’s author, adjudicating between the two centuries in equal perturbation. As Pierre surveys the abandoned and repurposed warehouse he has come to seek asylum in, where he will re-write his second novel in service of Truth incarnate, he appraises the group’s leader, certain of his knowledge of “the great lie, hidden behind everything.”

Truth and illusion therefore give way to swirling ambiguity in a work unfortunately slotted out of time, too washed-up for youthful alacrity, too nascent for wholesale irony. Yet ambiguity, in spite of all, is what imbues Pola X with all its mesmerizing élan. As the film mounts its bitter final stand against propriety, Depardieu fils dons the age and angst of Depardieu père, a hunchback and walking stick to accompany the death drive soon to manifest. Pierre renounces literary anonymity, but retracts his renunciation, only to meet with fatal rejection. Isabelle gazes, unmoved, at a picture of her father. She attempts to drown, but is saved. Thibault, the long-estranged cousin, aims to avenge Lucie. He challenges Pierre — for the miniseries, Carax intercut a shot of him watching, via television, a regretful Pierre awaiting Isabelle’s fate. Pierre accepts. Amid a torrent of paper and gunpowder, a tearful Isabelle confronts Pierre, as if to deny the responsibility of her confession. “I have always told you truth,” she avers. As if he didn’t already know, and as if Pola X, all this time, did not circumscribe the wisdom of David Foster Wallace in its impassioned frames: that the truth will set you free, but not until it is finished with you.

Comments are closed.