The first idea that can be discarded with regard to Paul Schrader’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, the acclaimed 1985 film centered on the life of celebrated and controversial Japanese author, poet, playwright, model, actor, director, right-wing political activist, and eventual leader of his own private militia, Yukio Mishima, is that it was born out of a fascination Schrader had with his subject. The truth is that, like most great American filmmakers of his generation, perhaps even all, his fascination lies mainly with himself. Mishima, then, is hardly about the person it purports to be about. On the surface, of course, there are the biographical elements, by turns tragic, lurid, and shocking, that function as a rack for the writer-director to hang his own preoccupations, neuroses, and obsessions on. The exact circumstances of his life — or more specifically, his death — are commonly absent from the brief author’s biographies on editions of his books: Yukio Mishima, a pen name, was born Kimitake Hiraoka on January 14, 1925 in Tokyo City and died on November 25, 1970 on the Japanese Army’s Ichigaya base, committing seppuku after a failed coup d’état during which he sought to restore power to the emperor, an episode which is referred to as the “Mishima Incident” in Japan.

For Schrader, however, the author’s biography is merely a means to an end, incidental on its own, only of interest as it relates to both the subject’s work as well as Schrader’s. Segmented into the titular four chapters — Beauty, Art, Action, and Harmony of Pen and Sword, titles that are remarkable in their naked invocation of fascist aesthetics and indicative of Schrader’s implicit adoption of his subject’s reactionary worldview or perhaps an already present overlap that drew him to the infamous figure in the first place — the film dedicates a majority of its runtime to adapting Mishima’s elegant, seductive prose to the screen to create a kind of mosaic that purposefully blurs the line between fact and fiction, ideas and action, theory and praxis. In Mishima, the character of Mishima emerges not from the specific circumstances of his life or social context — at least not exclusively: the shadow of World War II and, crucially, Japan’s defeat which mirrors Mishima’s own cowardice, certainly looms large — but from the words he left on the page, words that would prophesize the blood, his blood, that would eventually be spilled in the real world.

But the blood spilled isn’t just Mishima’s but Schrader’s as well. When the members of Mishima’s private militia commit themselves to attempting the violent coup, they sign their names in blood, a gesture that becomes not merely political but signals their commitment to the art project that is Mishima’s life and, by extension, an aesthetics that in turn allows a (rather incoherent) strain of reaction to emerge. It is also where Schrader gets to bloodletting: he sees something of a kindred spirit in Mishima, someone totally, completely, and unapologetically committed to an idiosyncratic vision — the politics, largely at odds with Schrader’s professed views, his occasional Facebook rants about “wokeness” notwithstanding, are just one part of a larger artistic whole and a negligible one at that. If Schrader’s Mishima ever feels disillusioned, hopeless, alienated, or misunderstood, it is only because Schrader himself has felt this way — the cracks of the carefully manicured, larger-than-life image are where the filmmaker pours himself in, cracks which Ken Ogata’s wonderfully Stroheimian lead performance continuously allows to seep in.

This is the second idea about the film that can be discarded: that this is a biopic of Mishima in the first place. The avatar Schrader puts on screen here is Mishima the art piece, the human being who, to quote from Kyoko’s House, one of the three novels the film adapts, “devise[d] an artist’s scheme” to preserve himself in amber at the ostensible height of his beauty. Given the fundamental truths of death — there is no glory in dying, whether it’s for art, politics, or from existential despair — it’s perhaps no accident that he never actually shows us Mishima’s, instead opting to cut the film short right as the sword pierces his skin of his lower abdomen, a freeze frame leaving the audience to be awed (or possibly disturbed) by his warrior’s determination and discipline.

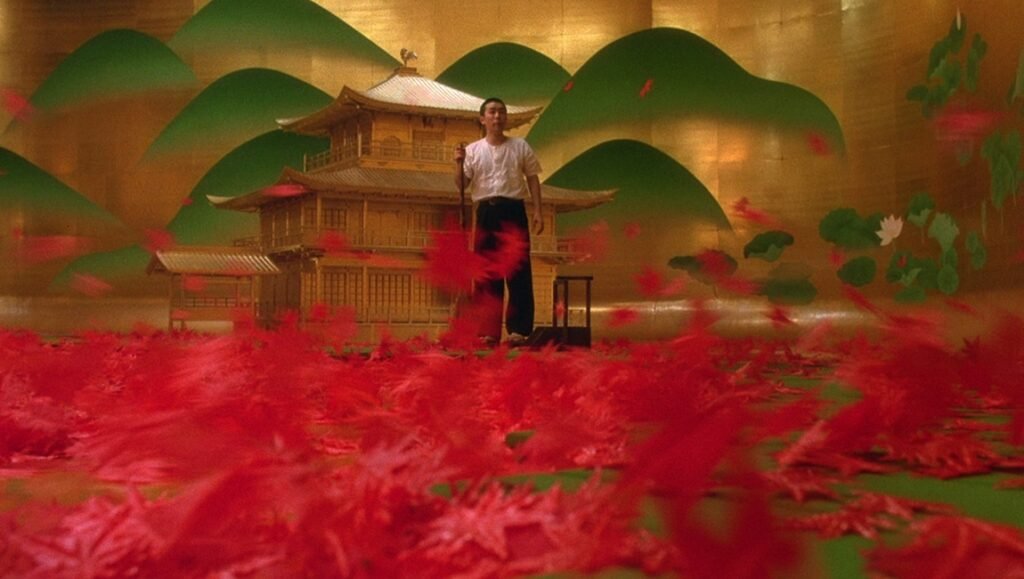

After two hours of showing Mishima maintaining his composure, only occasionally broken up by moments where his playful charisma shines through the stoic façade — at one point he even entices the leftist university students he debates at the Zenkyōtō-occupied Tokyo University enough that they, somewhat begrudgingly, applaud his fanatical devotion to the emperor — the coup attempt itself plays as remarkably anti-climactic (“I don’t think they even heard me,” he says after delivering his ill-fated speech to the garrison, his momentary dejection being the only indication that his goals might have gone beyond mere aesthetics and toward something resembling concrete political aims), something which is sharply contrasted with the orgasmic portrayal of the ritual suicide itself, a scene that is intercut with the climaxes of the three adaptations of his fiction — the titular temple being set ablaze in The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, the lover’s suicide that concludes a sadomasochistic relationship in Kyoko’s House, the sunrise-lit seppuku of Runaway Horses’ would-be putschist — all playing out as Philip Glass’ wondrous score swells in wide-eyed admiration.

The ominous hum echoing through Mishima’s literary voice is given a visual shape by Eiko Ishioka’s lush production design; the sets and color schemes are also a rare instance where Schrader draws clear lines between the world of fiction, of ideas, the world of memory, and the real world, i.e. Mishima’s 1970 present. His childhood as a sickly, pitiable boy, elements of which are taken from his supposedly autobiographical novel Confessions of a Mask, is shown in a black-and-white that recalls Yasuzō Masumura’s 1961 drama A Wife Confesses; the novel adaptions bloom to life on colorful, fragmented stages, the hazy cinematography and soft contours evoking something out of a dream; the present, meanwhile, is treated in a more naturalistic, matter-of-fact way, eschewing elaborate sets, vivid colors, and blocking. It is, without a doubt, the aspect of the film that goes the furthest in illustrating the interplay between the different spheres that contribute to the writer’s popular perception.

But where does this leave the Schrader-typical “character study” of it all? (This being a character study is perhaps a third idea that deserves to be discarded.) Given his somewhat enigmatic nature and contested aspects of his private life, it could be argued that buying into the myth Mishima constructed around his person is the only meaningful way to approach him rather than engaging in conjecture about what what is or isn’t “true,” a distinction that is almost entirely meaningless in spite of the constant audience and critical squabbling over historical fidelity. Schrader never really gets to the heart of the “real” Mishima because there is no such thing. The piece of art Mishima made himself, his life and death, into was the real him, his ultranationalist vision of Japan, his obsession with beauty, with the archaic, as well as with the transgressive, the shocking melded together to create something that was, indeed, a character, albeit one that resists conventional psychological study, at least as it exists in cinema.

Mishima reveals its true depths when taken as a filmic work of literary criticism, a kind of visual essay that allows the audience to navigate the ways in which one of the most mystifying figures of the 20th century’s life, beliefs, and art intersected. The result borders on hagiography but is also undeniably rhapsodic. The film ends with the coup leader of Runaway Horses (played by Toshiyuki Nagashima, who starred in Kichitaro Negishi’s underrated drama Distant Thunder four years earlier) slicing open his stomach, laboriously dragging the blade from left to right — this, by contrast, is actually shown on screen — as a voiceover reads from the source material: “The instant the blade tore open his flesh, the bright disk of the sun soared up behind his eyelids and exploded, lighting the sky for an instant.” His eyes widen for just a moment before he collapses, his expression never changing. It is the mystery of what he sees, thinks, and feels in that moment that animates Schrader — the most meaningful point where he and Mishima diverge. The one gap he can’t bridge.

Comments are closed.