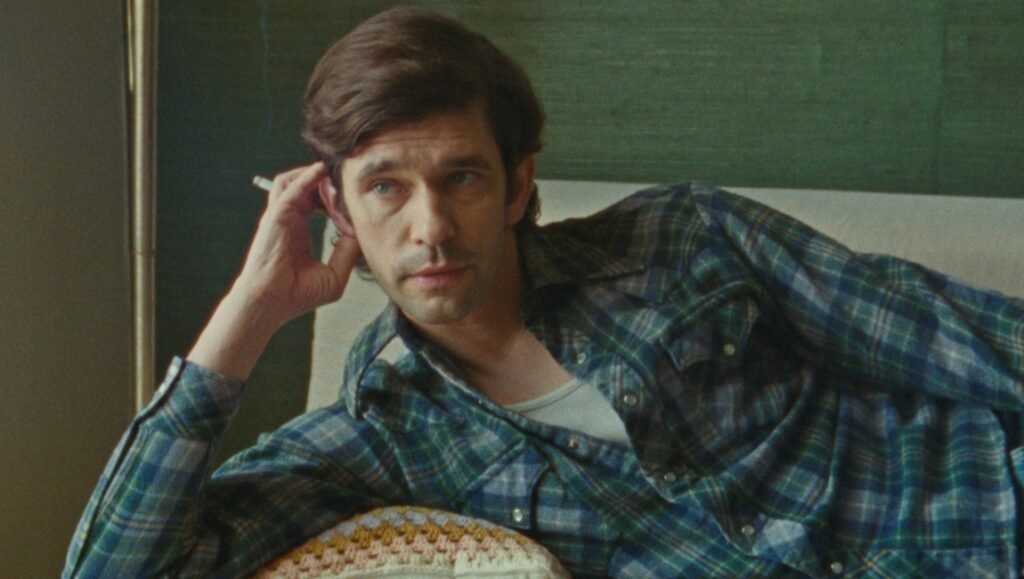

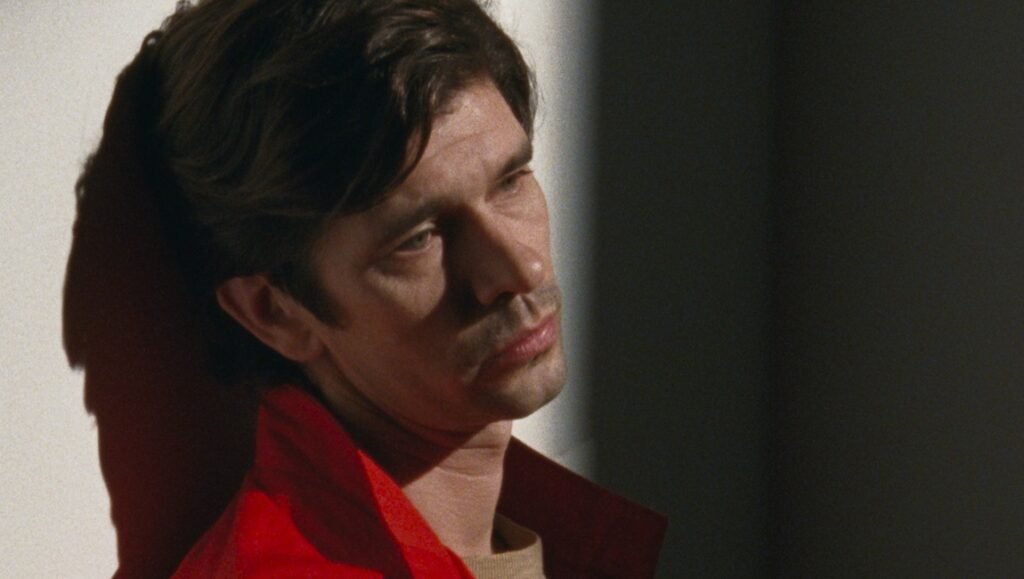

With Peter Hujar’s Day, writer-director Ira Sachs reteams with actor Ben Whishaw, trading the contemporary Paris of Passages (2023) for 1974 Manhattan. Whishaw stars as the titular portrait photographer as he recounts in great detail his previous day to journalist and friend Linda Rosenkrantz (Rebecca Hall). Whether discussing if two naps a day is too many, or worrying about a friend who eats too much junk food, while Rosenkrantz worries about his constant smoking, Hujar’s account is completely enrapturing in its banality, recalling the likes of Proust or Knausgaard. Sachs’ adaptation of Rosenkrantz’s book and original transcript revels in the small moments that manifest when two close friends hang out in private, while also acting as a timeless meditation on the difficulties of being an artist. It’s also a special glimpse into the bustling New York art scene of the mid-1970s, with its anecdotes involving Allen Ginsberg, Susan Sontag, Glenn O’Brien, and countless others, both known and unknown.

I spoke with Sachs over Zoom ahead of the film’s release on November 7, where we discussed balancing the film’s playful formal touches, sitcom hit Frasier, and how artists in cities hang out then versus now.

Caleb Hammond: After reading the book and then discovering the full transcript, how did your interest in this material develop into a movie? And then how did you develop the formal rules that govern the process? Was there a rule about only using the transcript dialogue, for instance?

Ira Sachs: The initial impulse was this incredibly intimate text that has all the detail that I love in any movie and puts you right in a relationship in the most intimate way, between these two friends. And then I was working with Ben Whishaw at the time, and I wanted to continue to collaborate and make things with him. So those elements all came together, and I thought, I should make something of this movie. I never thought of it any other way than what it turned out to be, which is a filming of the conversation between Linda and Peter that took place in December of 1974. That’s what I was going to be doing. The challenge, maybe a year later, when I had all the elements together, was how to film it. It’s by nature a stagnant idea, which I’d never want to make a stagnant movie. I’m trying to make action films in my own way, films of cinematic movement. To figure out how to transform something that was very still into something that was ultimately a series of about 23 different scenes, was the challenge. That process took some time and some dark nights to be honest.

CH: There’s a music cue 30 minutes in where the visuals switch into a distinctly portraiture mode, and there are scenes that break the realism of the interview, when they’re smoking on the roof but the tape recorder is not up there with them. You break the rules of the interview. Was that a breakthrough, realizing that you could do that?

IS: What I loved about it was that there were no rules. There wasn’t a rule of how long the movie would be. There wasn’t a rule of how real or unreal it was. That being said, there are no rules, but you still have to hold a certain logic. You can be abstract, but you have to create a logic that the audience begins to trust and feel comfortable in. So that was a line. There are two moments where you see the artifice specifically of filmmaking: you see a clapper, and then you see a sound crew later. At some point, there were maybe four of those moments, but four would have felt like too much. I wanted it to be just above unconscious. You’re finding a balance in which you create, ultimately, if you’re lucky, a trust between you and the audience, that the film has logic, even if the logic is not literal or simple.

CH: You could argue the track at the end, which ends with audience clapping, plays like the end of a movie playing in a theater. So that’s a filmmaking element at the beginning and end of the film.

IS: There’s a story being told which begins with a clapper and ends with clapping. I’m drawing attention to the fact that the film is both real and unreal. The fact that Ben Whishaw and Rebecca Hall are both British people playing American characters was, for me, something very new, because I’d never worked with accents before, but also liberating, because I wasn’t attached to realism anymore. There was no way that this was a realistic film, just by the nature of Ben transforming himself into Peter Hujar.

CH: You don’t like rehearsals, and so for this role, Ben had to memorize a lot of lines on his own. When he’s doing that, is he completely on his own? Are you checking in on him?

IS: I checked in a few times. But there’s an enormous amount of trust. I basically was like, “Are you learning it?” And he’s like, “Yes.” I’m not like, “Are you sure?” or “Show me,” or anything like that. There was this beautiful trust. I never knew if he knew the lines until we got to production. If he hadn’t, it would have been quite challenging.

CH: It’s probably helpful that you worked together in a similar mode on a previous film.

IS: Yeah, but this was an unusual task, and somebody could do an interesting interview with Ben about the learning of those lines, because in the same way that Peter’s dialogue with himself about the shooting of a photograph of Allen Ginsberg is so detailed and circular, and it’s not simple. It’s not like Peter Hujar photographed Allen Ginsberg, end of story. It’s a million more things. I have a feeling that Ben learning these lines was a million more things.

CH: Ben Whishaw’s Day.

IS: Ben Whishaw’s Semester.

CH: What stood out the most when you were going through this transcript — what captivated you? 10 people who love this movie could have 10 different favorite scenes. There’s so many little things that you can attach to.

IS: It was a general pleasure in hearing the story told and with such detail. In time, as I shot the film and then edited and now live with the film, there’s like 40 details that I just love. I love when Linda says something that she thinks is interesting, and Peter doesn’t notice. It makes me laugh every time when he just doesn’t listen to her. That is actually not in the text, that’s in the performance, but I love that moment. I love the conversation between Peter and Linda on the bed when they’re talking about Bette Davis and Joan Crawford. That little dialogue, which is one of the most intimate and playful, was edited out of the book. I like that I reclaimed one more indelible moment of this day in the film that would have been lost, like everything is lost. Everything is lost. But somehow this film claims and holds as a monument the details of this day, both the day that they were together talking, but also the day that is being described. But the thing that I most respond to is the transparency and the openness in which Peter conveys how hard it is to make art.

CH: And to make a living as an artist.

IS: Both of those.

CH: Living in a city like L.A. with all these little scenes of people, it’s funny that there’s forever this balance of making art, which can be a very solitary practice, versus the hubbub of knowing people and having to hang out with other artists. Forever this balance is being struck by people in cities making art, then and now.

IS: And also, more these days in isolation, because there’s less artistic community-building, in our global economy, in our global virtual worlds. And this film is testament to the value of being with other people, talking about your day.

CH: There’s something really nice about the concept of dropping in, in hearing about Glenn O’Brien dropping in on a friend. That’s pure. Everyone’s hanging out in the same neighborhood.

IS: Does that happen in your L.A.?

CH: Not at people’s homes, but you might know that certain people hang out in certain places, and so you go to that place expecting to see them, and then you see them. And that’s a similar way of dropping in on somebody.

IS: I don’t think that happens very much in New York, at least not when you’re 60; maybe when you’re 25. At my age, it doesn’t happen so much.

CH: I find the Ed Baynard story compelling, because Peter is shit-talking him, but then in the press notes, it says that they’re close friends. And you realize he is talking about Ed Baynard in a way that you could only talk about somebody you are close with.

IS: I feel bad for Ed Baynard, because he seemed like a good painter. I feel like Peter throws him under the bus, but I do even more because I made it into a movie. We all trash-talk our friends, but we don’t expect it to be in a movie.

CH: Like Ed Baynard, I am very good at keeping people on the phone. It’s this skill I have. My brother-in-law tries to do it with my sister, and he can’t. He doesn’t have the skill.

IS: That’s really funny.

CH: I don’t think this movie is too inside baseball, in the sense that I know some of these references, and maybe it’s a little richer because I know them. But a majority of them I don’t know. And it doesn’t affect one’s viewing of who they are in relation to the story, because that’s not what’s important in the story.

IS: That’s what’s interesting about Ben’s performance: he didn’t know any of them. Nobody knows all of them, including Linda. There’s still four people we can’t figure out who they are. But everyone’s equal. They either come to life through Ben Whishaw’s performance, or they don’t. It doesn’t matter if it’s Glenn O’Brien or Susan Sontag. Notoriety doesn’t make them more valuable to Peter and Linda. It’s about familiarity, and that is what I didn’t know that Ben would do so well, and that’s why it became a feature film, because it was so compelling, because it was a person sharing their whole world in a way that was unexpected.

CH: Weirdly enough, it reminded me of why Frasier was so successful. Frasier includes all these highfalutin references, to the opera for instance. And it was a huge hit, even though most people don’t know many of the references. But like in Peter Hujar’s Day, getting the reference or knowing the name isn’t what’s important.

IS: I’ve never seen Frasier, so I didn’t know that. That’s very interesting.

CH: Frasier and his brother always end up in these screwball situations, and so what’s important aren’t their throwaway references, but the ridiculous situation at hand and the characters themselves.

IS: That’s exactly right, and that I trusted. In the same way, if you read a memoir, you become more curious about a time and a place, but it’s not necessary for the experience of the film.

Comments are closed.