In the years since the latest round of Israeli occupation and destruction of Palestine, the people and lives we see are often the ones who have been murdered. We’re shown necessary images of the brutal, repeated aftermath of a violent genocide, but it’s more rare to be given a glimpse into the lives of those who are forced to live like this. And not only get that glimpse, but hear their hopes, their dreams, their desires.

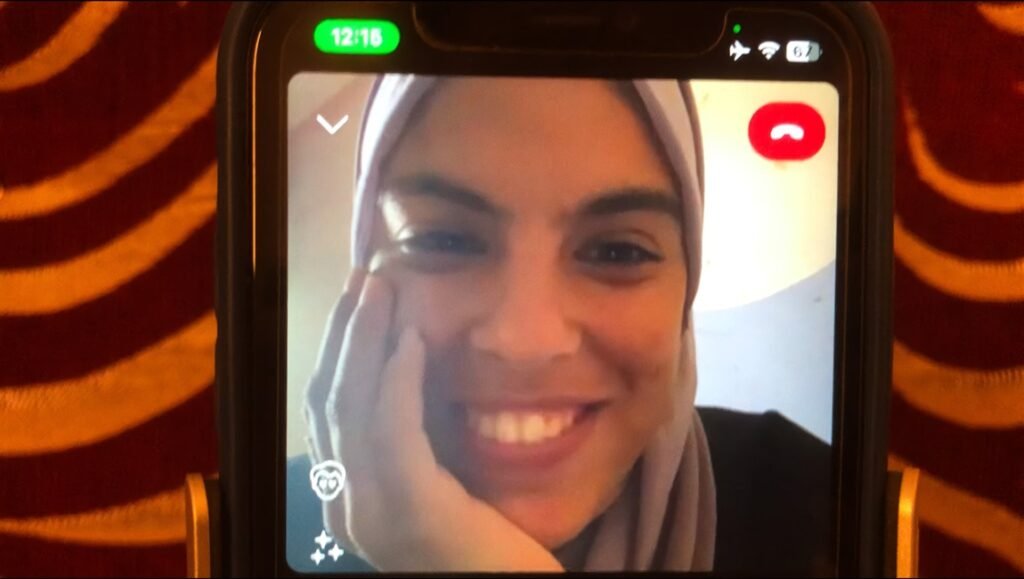

For over a year, filmmaker Sepideh Farsi kept up a correspondence with Palestinian photojournalist Fatma Hassona, and the result of that is her new documentary, Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk. Their FaceTime conversations, ranging from everyday things like cats or what one had eaten that day to the larger existential threat Hassona lived under were all captured by Farsi. These conversations show a woman determined not just to fight back and survive, but to truly live. A woman who couldn’t understand why she and her people couldn’t simply be, but in spite of it, created art, wrote poems, played music. These glimpses into Hassona’s life are shown from the phone, camera pointed directly at it. Interspersing Hassona’s photographs with the conversations, Farsi takes a tool used primarily for beaming death to us and reformats it as a beacon for life.

Hassona is an astonishing subject. Always laughing, the first to try and make another person feel better, you sometimes forget the life she’s been forced into. In her lies a gentle power, and through every pixelated, fuzzy frame on Farsi’s iphone, Hassona’s hope for a better life for herself and her family remains steadfast, her resistance being the very fact that she’s living in the face of occupation. Farsi, herself no stranger to resistance — having done real prison time in her home country of Iran for harboring a political dissident — allows these conversations to flow into one another gorgeously. Through her frequent meetings with Fatma, we’re allowed into a Gaza as it is. Attacked, occupied, but never broken, its people always rising for another day.

Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk was selected for Cannes on April 15, 2025, with Hassona meant to attend the ceremonies with Farsi. Just one day later, Israeli forces murdered Fatma Hassona and some of her family, dropping a bomb on the building in which they lived. With that, they extinguished a life that, at just 24 years old, was only just beginning. They took from the world a poet, a musician, a photographer, and a dreamer. A woman who saw horrific circumstances every day and still chose to wake up and live. Farsi’s film is a vibrant testament to that life, and a document of just one of the countless lives that’s been taken.

As the film hits theaters, I sat down with Sepideh Farsi to discuss the film, the light that was Fatma Hassona, and what Farsi sees in the film now, after Hassona’s death.

Brandon Streussnig: What struck me more than anything else was Fatma’s optimism. It’s devastating to watch in any context, but especially now. It’s also stunning to watch someone in her situation often go out of her way to try and cheer you up. It makes you think about your own privilege, more than a film like this already does. Can you talk to me about that? Where do you think that comes from? Was that just her nature?

Sepideh Farsi: I was thinking today that we don’t even notice the privileges that we have just to get up and open the tap and get water, or to even choose between all the things that we can drink and eat. We forget what scarcity and what hardship Palestinians — specifically at this moment, but also always — go through. To answer your question, it’s hard. Sometimes I did feel that she was almost minimizing or exaggerating her state of mind. Almost making herself brighter. I think part of it is due to the fact that she felt good about me when we met. It was always a pleasure. That is one part of it. I think when you are looking forward to an event, and especially when you’re not doing very well and something is boosting you, I think it did really bring something to her.

The rest of it is her own personality. She was such a vibrant person, and I think she really did hold onto life that way, in a way, because she also had faith. We discussed that a lot. I think that part of it is linked to the way Palestinians in Gaza are brought up because they’re born in captivity. She was born in Gaza and was killed in Gaza, never set foot out of Gaza. So all they know is this. That’s also why she says, “All we have is Gaza and my Gaza needs me.” I think it’s a way of holding on to that God that they believe in. It’s a mixture between her ethnic and social group upbringing, let’s say, and her personal energy, which was amazing. She had so much light in her.

BS: You brought up your discussions of her faith. What took me most aback is that your conversations with her are so frank and open. You’re both always so willing to disagree with one another. Was there a structure to your conversations before you called her each time, or did they just flow depending on the day?

SF: It was more the latter. I did have themes in mind that I wanted to talk about, but if I felt that it wasn’t the appropriate day or time, I would refrain. But the thing is, it was not a relationship of somebody who’s filming or interviewing you. Typically, if I’m coming to you, for instance, you’re a journalist, we don’t know each other… it’s not that I’m wary of you, but I wouldn’t tell you everything.

BS: There’s a performance to it almost.

SF: Yes, yes, exactly. But if you’re meeting a friend or a person whom you trust, there’s a different way of putting things. So room for disagreement, for instance, or me asking different questions that could have been hurting, or maybe not hurting but putting her in a defensive position. I didn’t feel that. Because when it comes to affection, and if you feel okay with the other person, you can talk about everything. When she would tell me, “I would like to believe you, but I don’t,” for example, we were disagreeing about certain things, and that was it, but it didn’t matter because it was just a fact.

BS: The choice to frame the conversations the way you do, by shooting your phone so you can see it in its entirety through every FaceTime call, is so engaging. It’s like you’re taking this tool that’s been used to convey Palestine as one thing or one idea to us and using it to present daily life. Was that always the conceit?

SF: I felt that that was the appropriate way of filming our conversations. The first day, I did it because I already had an intuition that this was the right way of doing it, and it proved right even more so as we went on. In the moment you don’t analyze, you don’t make choices, but there are emotional choices or aesthetic choices, and you don’t necessarily, at that point as a filmmaker, analyze your own choices; you do it later, or other people do it for you. But now that I look at it, I think it’s the right way of doing it because it’s exactly, as you said, through the same technical means that usually give us images of mutilated bodies and destroyed landscapes, and an annihilation of people.

Through those same means, I wanted to show humanity. I didn’t want to make it beautiful, I just wanted the same exact fragile connection, the same exact way of filming that Palestinians use to send us the images of the genocide. I wanted my focus to be solely on her face.

BS: I’ve read that you have hours and hours of conversations with her. How did you make the decision of what to include versus what to leave out? And then, how did you decide on which of her many photos to include in the film?

SF: I really let myself be guided by emotions. I tried to build an emotional arc between us through the conversations, so each conversation, just so that you have an idea, is one-to-one and usually a half hour long on several videos, and they’ve been cut to something like 10 minutes each or so for the film. I kept the strongest ones, and I also tried to reduce the number of conversations. So many of the conversations that we had are not in the film at all because they corresponded to moments that were perhaps not as strong, or she or I weren’t as articulate, or our conversation was not as emotional. I think that was the guideline for me on what to keep and what to let go.

Regarding her photography, one of the other choices that I made that was deliberate from the beginning of the editing was to leave the distraction and the war in the soundscape of the film. So you hardly ever see any of that except in her photography. During our conversations, sometimes I told her to go to the window to show me what was out there. But other than that, and the sound of the military devices that were flying over her head, we didn’t have anything else. No other images, photos, or videos could illustrate that violence. So her photography was the only moment that I showed the destruction explicitly. That came a bit later during the process of editing.

First, I made collections, lines of her work as a puzzle put together, and then I designed the sound for it. So it’s maybe music, or it’s her poem, or it’s her song, or it’s silence. That moment where the child is washing the blood and flesh off the street, that I learned later was his own family, that’s the only moment that is very graphic. That’s the alchemy of what I wanted to show.

BS: Are there plans for her remaining photographs to be shown anywhere?

SF: Yes, there was a book that was published in France, which is called The Eyes of Gaza, and I hope that it will be translated into English as well. That has more than a hundred of her photos. There are also exhibitions. There will be more, yes.

BS: I really appreciated that you let her give her honest thoughts about October 7. We’ve only ever had it, and the reactions to it, filtered through one lens. Of course, it would be viewed differently by the people currently under occupation and oppression. It was refreshing to see someone speak so honestly about it in relation to the life she’s been forced to lead. It’s easy to look at something like that as a tragedy, but when you view it from the perspective of Fatma or any Palestinian, it’s like, well, what do you expect them to say or do?

SF: That’s exactly where the film started from. It started from a missing narrative for me, the need to make this film. The problem is that the world has been concentrating on this tragedy of October 7, as though that was the starting point of all of this. It’s not. When you start addressing that, they say, “No, but you have to condemn October 7.” Okay, condemn October 7, but go back more than 100 years ago and see when it started and where it started, how it started. And then let’s discuss October 7.

It took me months to be able to ask her this question. This was probably one of the hardest, because I didn’t want to hurt her. And I also, if ever, there was one moment where I thought, “Am I legitimate to ask her this?” I thought, “Who am I to ask her?” And when people ask me, “Why didn’t you ask her to condemn October 7?” And I said, “The film is not a political analysis.” I asked her how she felt. I didn’t say, “Give me analysis,” because she’s not a politician, I’m not either. I wanted her feelings to see whether she realized when that happened, that her world would never be the same.

When I heard about the attacks, I said, “Oh, it’s all gone.” I mean, it’ll be hell, and hell will break loose. And it did. We knew that, but for them, from their point of view, I think they didn’t even know what was happening. They were among the last people who learned about the attacks, the Palestinians. In the film, she says, “First, I thought it was yet another Israeli attack.” It takes hours because the communication is cut. So then they get the news at some point, a few hours later, what has really happened. She doesn’t even say, “Fight back.” She says, “Resist.” These are her words. She says, “We showed the world that we can resist with empty hands.” She is something to reflect upon. As you said, why is it that Palestinians have to let themselves be pushed around without resisting? Why?

BS: It can be so frustrating to be asked to only condemn and never acknowledge the decades and decades of violence and occupation. Seeing her speak so freely was so moving. What has the response to this been like for you? Beyond the people it may have resonated with already? It shouldn’t take a film like this to build empathy, but has anyone approached you with a changed mind?

SF: I think so, yes. There are always a few people who say, “Ah, perhaps she should have been more articulate about condemning Hamas.” But for most of the people, I’ve heard many people telling me that this film changed them forever. One person, he’s a programmer actually, and so he sees many films, and he said, “I thought I knew about the conflict. When I went to watch your film, my presumption was that I was well-informed. And I sat there, and when I came out, I wasn’t the same person anymore. My view changed.” That’s what he told me. I get this in different ways from the audience, who sometimes don’t even know me, just find my address and write to me. I mean, I myself was recently walking on the streets of New York. I was like, “What do these people know about what’s going on in Gaza? And what do I know about Sudan?” Because now with El-Fasher, it’s horrible. It’s such a disaster, and things are only coming out little by little. Why haven’t we been taking care of that earlier? We let it go so far.

BS: Do you think there are limitations of cinema as a tool for political action or revolution?

SF: I mean, that’s always the thing. Is cinema a political… I mean, are arts and politics separate? Could they be converging? How political should cinema be? The festivals?. It’s always the same. It’s a tightrope because I don’t believe in pamphlets as films. A film has to be a film. It has to have a cinematic quality. It’s the same with art. You could make Guernica, or you could make some sloppy thing that you could hold in a rally, and it’s supposedly a painting, but it’s not.

It’s very hard to find that borderline between something that really is art, but is also a piece of political opinion. Or, something that is only political and something that is not at all political, which is never really the case. This is very true in the case of American movies; American soft power is as strong as its military power. For decades, it has been winning the world. It’s something to reflect on.

BS: Did you know in the moment when she said, “You have to put your soul on your hand and walk,” that it would be the title of the film? It’s such a powerful, beautiful statement.

SF: No, that came later. I was editing already, and I fell upon it when I was listening to her audio messages. She said that in a message that she sent me. I had noticed it back then, and then it just passed. But later on, because the process of editing was that I would work on the images of our conversations primarily and then I would pick up things. When I found that one again, I asked her about it and she didn’t even remember it well. It simply emerged because that’s what she was doing at the time.

BS: It really speaks to her mind as an artist. To be able to fire something so profound off like that and forget about it.

SF: It also had to do with the way she spoke English. She would build images with her words. Her English wasn’t that fluent, but it was so beautiful. In not being fluent but so beautiful, she would then, instead of knowing a word, would go and build an image with words, which is exactly what she did in this phrase.

BS: I want to thank you for sharing Fatma with us, the way you got to see and know her. I’m so sorry for your loss. It’s a tough question, but has that affected the way you’ve been able to view the film. Did anything change about it?

SF: When I watch the film now, of course it’s the same film, but it’s not anymore because I try to see things beyond the image, beyond the frame, beyond her words. It’s as though I’m looking for a premonition, premonitory signs where probably there were none because we were just having these beautiful moments together, very strong ones. It’s also hard because of the content, but great moments of bonding and exchanging. But now, of course, one thing that is strange and happens every time the film starts, it’s as though she was alive. As if she was here. She comes out of the frame. I mean, she’s so vibrant.

The other thing is that I keep looking for things like, “ah, I hadn’t seen it this way.” I can’t stop myself, just reinterpreting what we were telling each other. Whereas when we did it, I don’t think she was aware that she would even be targeted. She wanted to live. She wanted to come to France, to come to Cannes with me. We both believed in that. We thought we made it on that last day when we talked and I really thought… I was so happy. I was just like, “Wow, we did it. We did it. We made this film despite everything.” And yes, we did it, but she couldn’t come.

Comments are closed.