The world of Terence Davies’ Distant Voices, Still Lives is shown to have disappeared into the amber hues of the past right from the start, when the Davies family stand-ins at its center are heard and not seen as they wake up in the morning. Only the house’s hallways and stairwells are on the screen, and the sound of the titular voices singing a song, then greeting each other and going about their day, makes the ghosts of Davies’ past briefly seem the friendly and invisible sort. The very real terror of Pete Postlethwaite’s deeply angry and abusive father soon rears its head, but Davies’ undercutting tendencies continue when the father’s softer moments emerge from the flow of musical memories. Still, what really lingers is Freda Dowie’s mother, a loving woman who nevertheless has an insidious tendency to put up with bullying behavior for the sake of feigned happiness. The “stiff upper lip” state of mind is all very well and good when it’s for oneself, but the line from forcing it upon one’s children to Davies’ subsequent empathy for lonely poets and entrapped women is a straight and direct one. The one small mercy is that she outlived her husband, but for most of what came of that, one needs to turn to Davies’ subsequent The Long Day Closes.

Touching upon one aspect of Distant Voices, Still Lives is like trying to isolate a single thread of a spiderweb, where the mesh-like nature means you’ll pull upon the whole no matter how hard you try. Outside of the avant-garde and Alain Resnais, it’s difficult to think of memory piece films where the scenes seem to bleed into each other so consistently, but the techniques used for the linkage are a little more grounded, and a little more recognizably rooted in the English language and its past cultures. Popular music of the 1940s and 1950s is constantly being sung by the cast of characters, or playing on the soundtrack alongside English classical composers like Benjamin Britten and Ralph Vaughan Williams. That sense of specificity to what the times were like is consistently maintained for period slang, tableau vivant staging decisions, and memory-fueled cutaway edits. Proust’s madeleine cookie dissolves into the tea, and the sweet and bitter tastes of the two become indistinguishable. Davies continually conjured up a blend of gay male diva worship and autobiographical projections of suppressive loneliness in everything he made, and he has never quite been possible to easily imitate. He was an anachronism even when he started out, and someone who disdained rock music but had a (reciprocated) deep admiration for Godard was perhaps always going to be at least a little original. Not referenced in the film, but perhaps the key cultural reference, is the kind of poetry that isn’t musical. Davies would explicitly tackle its writing in his late period biopics of Emily Dickinson and Siegfried Sassoon, but his particular fondness was to recite T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets at will, whose musicality on memory and creation suggests the key to the consciousness-fueled form he sought out. The quotations of popular entertainment, however, are closer to that of Eliot’s aptly-titled summit of British postwar pain: The Waste Land.

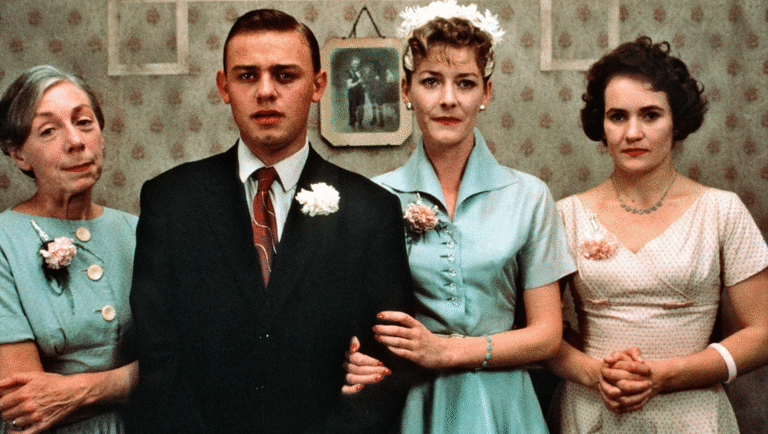

Distant Voices, Still Lives is not quite the most autobiographical of Davies’ early films about his childhood since the three siblings at its center are two women and a heterosexual man, and the three of them are designed to register a bit less than the shaping personalities of their parents and friends. (Two childhood friends of daughter Eileen have parallel arcs: the sassy Micky marries a man she initially wasn’t interested in and seems to grow apart from Maisie, while the more melancholy Jingles gets stuck with a bully who refuses to let her see her friends much at all.) It is, however, certainly the rawest and most anguished. The specter of male rage is inescapable, from the father terrorizing his wife and children, to the subsequent marriages that are abusive at worst and an act of settling for good-enough at best. Even when Postlethwaite’s father is dead, he sticks around in the form of what initially seems to be a ghost, but is then revealed to be his identical twin brother, whose mental abnormalities are thankfully more jokily eccentric than cruel.

Discussing the film as a whole is really a discussion of two films that got retroactively combined: after the 40-minute Distant Voices was completed, everyone involved realized they had a masterpiece with a running time ill-suited to theatrical conventions, and the cast reunited two years later to do it again for Still Lives. (The crew, however, had some key variations — most notably, the cinematographer switched.) Distant Voices is a purer experiment in cinematic techniques, one more rooted in childhood memories. Still Lives, meanwhile, finds the kids starting to settle into something more routine as they grow up and get married in their own right. Much like childhood, it’s a learning experience: the working-class women who endure all manner of awfulness from the men in their lives learn to use song or other forms of popular entertainment as their sole outlet. The apex of this comes when the two sisters cry to a screening of Love is a Many-Splendored Thing while the famous theme soundtracks a slow-motion disaster playing out elsewhere, as two of the family’s men fall through a skylight. There’s very little irony to be found to these quotations, and there’s not much doubt that even if Davies is falsifying or exaggerating some details — what are the odds that two family members would suffer the same niche accident simultaneously? — the way one thought leads to another is being preserved fairly loyally. The world that the Davies family inhabited has gone away forever, but at least there was someone around to document it in a fashion inseparable from how he reflected upon it. There’s some distance built into his own voice, but the lives of the past remain still and unchanging even as they unfold.

Comments are closed.