The Guilty

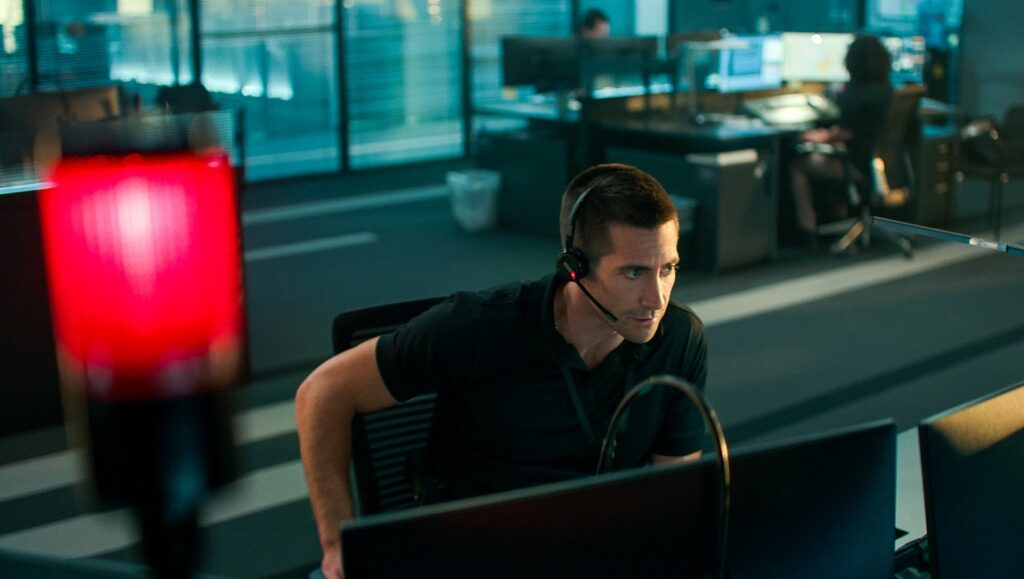

Antoine Fuqua has made a career out of directing populist, middlebrow fare that seeks nothing more than to entertain audiences for a few hours with slick, soulless thrills. It’s not that Fuqua is necessarily a bad filmmaker, but he’s the epitome of a competent director, which is damning enough commentary in its own right. But even Fuqua’s ardent defenders may find themselves grasping for a defense with The Guilty, the director’s second dud of 2021 after the dunderheaded Infinite. A remake of the 2018 Swedish thriller of the same name, The Guilty finds Jake Gyllenhaal in a mostly one-man-show as Joe, a volatile LAPD officer forced into 911 dispatch duty after some vague on-the-job incident has him headed to court in less than 24 hours. Set against the backdrop of the California wildfires — in a vain attempt to evoke tension and throw in a few monkey wrenches plot-wise — Joe finds himself on the receiving end of a phone call in which a young woman (voiced by Riley Keough) claims to have been abducted by her crazed and violent ex-husband. Unable to leave the facility, and using only a headset and the computer rig in front of him, Joe desperately tries to locate the woman before it’s too late, setting up a race-against-the-clock thriller seen and heard entirely from the perspective of our office-bound protagonist.

In premise alone, The Guilty seems to have tension baked into its DNA, with its claustrophobic, chamber piece-style setting and metaphorically handcuffed hero. But against all odds, Fuqua somehow manages to forfeit even this seemingly unassailable in-built tension with a spate of bland directorial choices that signal a filmmaker who just doesn’t care. There’s no distinctive style present in this setting so potentially ripe for formal play, no interesting camera set-ups or compositions. His style here is strictly point-and-shoot, with an overriding notion that the editing can save the day, a feat which proves impossible for Jason Ballantine, who seems equally asleep at the wheel. It doesn’t help that the script from Nic Pizzolatto is beyond lame, offering up a late-film plot twist that viewers will see coming from a mile away, and a protagonist who is far too unlikeable even for an antihero (Pizzolatto’s thing). Gyllenhaal, in what is essentially a one-man show, gives roughly 110 percent, as always, but is forced to play such a tired cliché that even his familiar mania can’t bring life or real energy to the proceedings. His backstory is straight out of Scriptwriting 101, and before long the film becomes yet another tale of personal redemption and atonement — fixed here on a bad cop; yikes — and is capped by the howlingly funny climactic line: “Broken people save broken people.” Journeyman genre director Brad Anderson actually delivered a similar tale eight years ago with The Call, a low-budget studio thriller starring Halle Berry that rather embraced the inherent silliness of its premise and delivered some fine-tuned genre thrills. No such luck with The Guilty, which is far too serious-minded for such shenanigans, entirely draining the film of any sort of fun in the process. If Fuqua’s film is guilty of anything, it’s in wasting the time of everyone involved with this rote, unimaginative drek. Let’s just hope the director doesn’t have another film up his sleeve before year’s end; we all need time to recover from this cinematic crime.

Writer: Steven Warner

Compartment No. 6

Single lodgings in a two-seater train compartment only afford so much privacy, and so in Compartment No. 6 Ljoha (Yuriy Borisov) and Laura (Seidi Haarla) confront each other before long. But why are they travelling to Murmansk, a multi-day journey that culminates in a port city on the decline? Laura, a university student with an interest in archaeology, wants to see the ancient petroglyphs. Ljoha is going there to work in one of its many mining sites. A tourist and a laborer, a wavering dilettante and an unyielding hedonist. Director Juho Kuosmanen isn’t interested in pulling apart the social conditions that separate the two; instead he knows these are the ingredients for an opposites-attract romance, and nowhere does he hide the crowd pleasing points of emphasis necessary to putting such a proposal across. The forward propulsion of the train is matched with surging handheld camerawork; mechanical cacophony is cut together with tightly produced pop songs.

Kuosmanen keeps the contingency of their brief encounter in view, however: Ljoha’s job prospects will be worse for him than he’ll admit, while Laura is particularly self-deceiving about the partner she left behind in Moscow, and there’ll be nothing to keep them together in the future. The nature of their bond, it seems, is not in fact their colliding differences, but the roles they’ve built up for themselves, and which they realize can be rescripted. Once they see themselves in this way, they travel somewhere near the territory of Capra’s It Happened One Night; it’s not for nothing that he’s content to sleep on the floor, and she wants to jump out a window (or that the world she’s leaving granted her nothing but paranoia for social distinctions, and that he peppers her with questions like a reporter would). Kuosmanen doesn’t populate their connection with symbols and comedic sequences in that particular Hollywood tradition, but he does get us close to the same problems of that film: of language and illusions, and the ways in which these problems require each to teach the other their own way of speaking and seeing and correcting.

I can’t speak to whether these similarities are intentional or not, or whether a full explication of the film would reveal it as a variation on the remarriage comedy (in Stanley Cavell’s consideration, likely not), but what I do know is that Compartment No. 6 is not a film where past sorrows need to be assimilated into a unified experience (“understanding the past helps us understand the present,” as the homily Laura unconvincingly quotes puts it), or where expressive romanticism is valorized for its own sake. Instead, what we see in Ljoha and Laura as the film expands beyond their relationship — to the other sections of the train, a romantic rival (Tomi Alatalo) who has a more conventional way of relating to Laura, and a parental figure (Lidia Kostina) who leads them into an almost pastoral interlude away from the mechanics and professional concerns of their meeting place — is that they know how to do whatever it is that they are doing together better than anything else. Usually the concerns of the limited-time romance are how to maximize every moment for significance, running the whole gamut of a relationship’s life and death in a compressed window of experience. But Laura and Ljoha learn another way of experiencing the world: that it may be best to do anything together regardless of its outward significance, even and especially if it is to waste time together.

Writer: Michael Scoular

Neptune Frost

Saul Williams & Anisia Uzeyman’s Neptune Frost is tethered neither to this world nor entirely apart from it. It’s both a queer film and an anticapitalist, anticolonialist one, and in its shape, it recalls science fiction narratives like The Matrix and Dune, but takes its own form as an Afrofuturist musical. It alternates between languages, between realms, between dreaming and waking, and between tones, and the visual palette mirrors this oscillation throughout as well, reflecting different moods and developments.

Produced in Rwanda, Neptune Frost is set in motion when Matalusa’s brother Tekno is killed by a boss while mining for materials used to build electronics. Matalusa then meets and falls in love with intersex hacker Neptune, played by both Cheryl Ishega and Elvis Ngabo, and they become part of a collective called MartyrLoserKing (also the name of Williams’ 2016 album in which he began to explore some of the themes present in the film) and begin resisting the society that is working to marginalize them — as members of the working class, as people of color, and as people who live outside of the West. Other characters filter in and out through various songs and segments, though it’s rarely clear how they affect or reflect the narrative.

More essential here is the ethereal music, composed by Williams, which matches the film’s techno-psychedelic imagery; it emerges from and then in turn shapes the diegesis of the film. None of the songs feel forced or out of place, and though most of them aren’t especially melodic, they successfully establish a mood and communicate the emotions of the characters. Neptune Frost’s unique costuming likewise stands out — during daytime scenes, they can be seen to incorporate computer parts, while during nighttime sequences, the neon lighting transforms them into something else entirely. These techno-centric visuals are also incorporated into the set design and the VFX, with some of the most memorable images including a man who flies using bicycle wheels as wings, wire face masks used to identify military members, cloaks made of computer keyboards, and a traditional string instrument that creates electronic music.

Though Neptune Frost’s plot is sparse and sometimes unclear, the film is not one that necessarily needs or wants to be plot-forward. That works out mostly fine, but unfortunately, despite its inviting technical craftsmanship, it does sometimes feel lacking in energy and propulsiveness. The performances, for their part, are engaging enough, but they lack the specificity of the direction and set design; most characters operate more as symbols and images than as fully-formed people, and it’s a particularly frustrating development for a movie with so much (successful) going on to fail to engage across the board and throughout the runtime. Still, its chosen thematics — gender, colonialism, technology — are richly explored, and so, despite sometimes lacking in coherence, Neptune Frost remains a worthwhile oddity on the strength of its formal expressions and its bold, novel exploration of a multitude of ideas.

Writer: Jesse Catherine Webber

Encounter

Riz Ahmed has made a well-deserved leap from character actor to leading man status in his recent work, beginning with the prestige HBO drama The Night Of and then his rapturously received performance in last year’s Sound of Metal. He’s currently garnering accolades for another music-based drama, Mogul Mowgli, and has yet another film in the TIFF ‘21 slate, Michael Pearce’s Encounter. You might say he’s having a moment, enlivening these various projects with fiercely committed portrayals of tightly-wound, emotionally-wounded men with furtive smiles and big, kind eyes that belie an anger roiling just below the surface. He’s a live wire, teetering on an impossibly fine line and threatening to plunge over at a moment’s notice. It’s a shame, then, that Encounter can’t surround him with a movie worthy of his performance, instead relying on belabored obfuscation to distract an audience rather than dig deeper into the ample drama already on display. There’s a good dramatic film buried in here somewhere, but writer/director Pearce doesn’t seem to trust it.

Beginning with a montage that shows a shooting star crashing into Earth, Encounter traces a chain reaction of animals ingesting some kind of microscopic bacteria, then in turn infecting each other as the food chain runs its course. Eventually, a mosquito lands on human skin and takes a bite, with the camera tracing this molecular invader’s progress from the mosquito through a human bloodstream. Who’s been bitten, and why, are questions that fuel the first half of the film, before being largely discarded as the narrative progresses.

Ahmed’s Malik Khan is introduced gearing up for some kind of mission. He’s got maps and blueprints and a loaded gun, and keeps spraying himself with an aerosol bug repellant. Soon enough, his mission is revealed: he’s kidnapping his children in the dead of night from his ex-wife and her new husband, determined to keep them safe from an extraterrestrial bug invasion. As Malik drives his two sons across state lines into Nevada, some of his backstory is gradually revealed; he’s a former Marine who did something like 10 tours of duty in the Middle East, and hasn’t seen his boys in over two years. Jay (Lucian-River Chauhan) is older, on the cusp of puberty, and has vivid memories of his father. Bobby (Aditya Geddada) is younger, and while he’s happy to see his dad, he doesn’t have the same connection with him. Malik explains to them that alien bugs are everywhere, having already assimilated half the world’s population (including mom and stepfather), and that he’s taking them to a military base for their own safety. It’s a potent set-up for a sci-fi thriller, but Ahmed’s performance clearly indicates that something isn’t quite right with Malik even before we meet Hattie (Octavia Spencer), his parole officer. She alerts the police when Malik misses a check-in, and once they discover the missing children, the FBI gets involved too, led by Agent West (Rory Cochrane). It’s here that the film begins entertaining the idea that all of this is in Malik’s head, and the narrative branches out to include scenes of Spencer’s character investigating the kidnapping as well as the federal agents working the case. Frustratingly, the film ceases to be a subjective exploration of a possibly damaged psyche and instead pivots into a full-blown suspense thriller, a kind of race against the clock as the FBI becomes convinced that Malik is going to kill his children. Once the narrative switches gears, the film loses much of its appeal, despite the cast’s best efforts.

Still, there’s plenty to like here; Ahmed’s performance is matched by the remarkable young actors playing his sons, who are initially thrilled to be on an adventure but grow increasingly weary of their father’s mood swings and violent temper. Much is made of how parents pass along their own trauma and neurosis to their children — infecting them, so to speak — and the need for children to learn to stand up for themselves. But scenes between Malik and the boys are constantly interrupted by banal sequences of the police pursuit and Hattie tracking down Malik’s old war buddies. There’s much effort expended on adding unnecessary tension to an already fraught situation, like a tedious sequence involving some militiamen who begin tracking Malik that devolves into a superfluous action beat. The real power here is in simple scenes of a damaged man trying desperately to reconnect with the children that barely know him anymore, while coming to terms with his own propensity for state-sanctioned violence. That’s a potentially great movie, and it’s a shame Pearce didn’t make it. Ultimately, Encounter gets swallowed up in its own high-concept, too concerned with its bait-and-switch to service its own characters.

Writer: Daniel Gorman

Huda’s Salon

The crucial difference between a genre craftsman and a filmmaker merely checking in and out of a thriller mode might be seen in the emphasis Hany Abu-Assad places on the photographic blackmail that sets off Huda’s Salon. Clearly, these exploitative pictures, which incriminate, violate, and coerce a series of women who imagine themselves entering the caring space of a salon, set the film’s plot into motion. Abu-Assad stages an exemplary scene of this to open the film, and follows it up with several cleverly choreographed long-takes before settling into a split narrative: the blackmailer Huda (Manal Awad), captured and interrogated, on one side, and her victim Reem (Maisa Abd Elhadi), paranoid and motivated in conflicting directions, on the other.

Each of them also has their shadowy, male doubles: Reem’s husband Yousef (Jalal Masarwa), the first to suspect she has something to hide, and Huda’s capturer Hasan (Ali Suliman), who orders a small group of the Palestinian resistance. Abu-Assad also has the panoptic presence of the Israeli secret service to work with: not only as part of the social reality background that his characters live in, but as a contact Reem could activate if she were to collaborate — this is the real intent behind Huda’s operation, and what the blackmail guards against. What Abu-Assad has, then, are forces that he can arrange to converge and recombine; yet he varies Reem’s emotional state based on the status of her blackmail, and surrounds Huda with these proofs of her betrayal. Abu-Assad would have it where a MacGuffin not only rarely leaves the frame, but only enables excursions into abstract ideas (the inequality of the sexes in married life) or typical evenhandedness (he sides with neither the resistance nor the collaborationists, regarding both at an incorruptible distance), rather than action between his well-developed characters: just as Reem is pressed into an impossible corner, the film contrives an ending. Or, you could say that Reem is offered an ending, and chooses to believe it.

Huda’s Salon is a return to Palestinian contexts for Abu-Assad, after the Hollywood tour of The Mountain Between Us. “You can learn a lot from getting closer to the dominant cinema industry,” he said at the time. It would seem that, if anything, this proximity has only encouraged a certain kind of carelessness in Abu-Assad’s cinema, one where genre is merely a pretext to gesture at loose connections to reality rather than the particulars of characters and their events.

Writer: Michael Scoular

Comments are closed.