Is there anything new to say about The Godfather? This might have been a worthwhile question even very shortly after it came out. The recent online brouhaha surrounding the A.I.-generated Pauline Kael pans in the trailer for Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis offers a clue as to how quickly it became the closest thing to a consensus favorite in cinema (although a little bit of searching would have turned up real reviews from Andrew Sarris and Jonathan Rosenbaum expressing reservations). It won the box office, the awards season, and the critical polls, and it continues to maintain its high perch comfortably. It is still the Coppola film, the New Hollywood favorite, and the gangster film; to say nothing of how much of the legacies of Marlon Brando, Al Pacino, Nino Rota, and Gordon Willis orbit around it. Some films are just that good at offering something for (almost) everybody.

Mario Puzo’s flashbang novel that served as the source wasn’t considered much even by the standards of bestsellers: there’s the infamous bit of trivia where it features an entire subplot about Sonny’s enormous penis. (Coppola reducing this to a wedding guest’s hand gestures is one of the cheekier cases of a director nodding to the book readers.) What it did offer was its own sort of trashy multitude of possibilities — a boatload of characters and bonds that would turn out to be right in Coppola’s lane, with his filmography’s focus on brotherly confusions and excessive feelings that go over the edge. It was his first real opportunity to fulfill his aspirations to create something like the films of Luchino Visconti after a series of groundling jobs and one unpopular experiment (Sarris noted that The Godfather wasn’t nearly as personal to Coppola as The Rain People, while conceding that it was probably better), and the rest became history.

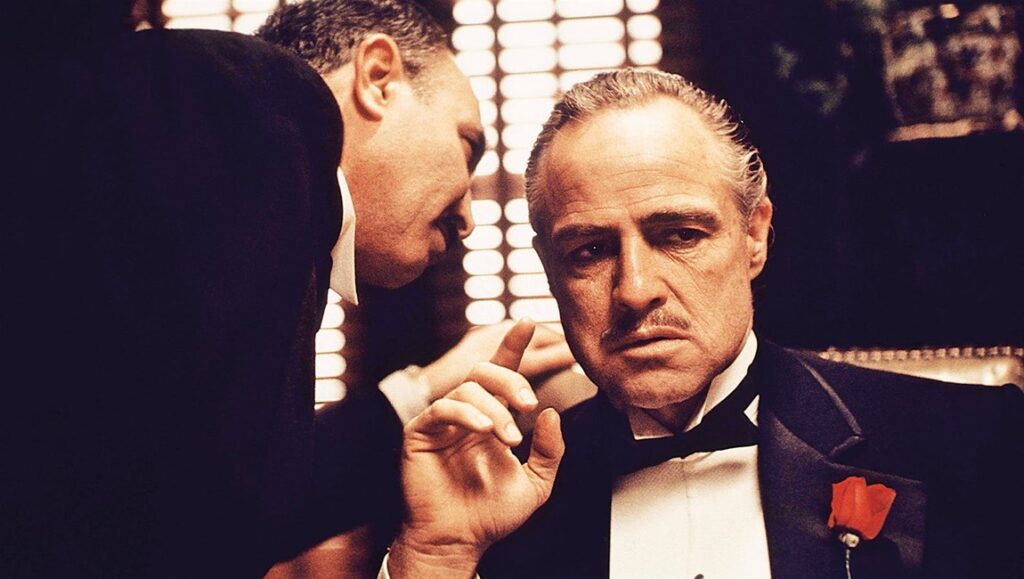

For all of The Godfather’s influence on subsequent film style and grammar, it was ultimately the work of someone from the film school system and didn’t avoid cribbing from a few of its own influences. (Rota did it the most literally by recycling a prior theme he had composed, knocking him out of Oscar contention.) Said influences mostly served as a contrast to the darkness conjured up by Willis for the interiors. Michael’s time in Sicily turns the film into a romantic melodrama not too far off from Rafaello Matarazzo, with the grunginess of 1970s film stock making the romance a little too yellow and shiny and bringing out the primordial quality of the old country. The opening wedding uses similar strategies in its overexposure, although there it’s to emphasize the black pit that is Don Corleone’s den. Brando’s odd jawline trappings, courtesy of Dick Smith, serve as his armor even as he deteriorates. (They form an intriguing contrast with the scenes where Michael takes a beating and his face’s condition serves to mark the increasingly rapid movements in time passing — one of the great visual exposition strategies.)

The Godfather’s influence is undeniable yet hard to pinpoint, starting with the fact that very few films took cues from the shadowy side of its allure, and not too many directors were granted the opportunity to sprawl out over three hours. (Michael Cimino’s own epic scene-setting wedding in The Deer Hunter, and his own subsequent attempt at a Visconti-influenced saga in Heaven’s Gate, provide clues as to where many Godfather aspirants would wind up — and he was already one of the more successful ones.) Despite its 18-year head start on Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas, there’s a legitimate claim that the latter’s needle drops, wilder explicitness, and use of voiceover are what tend to show up more as influences on the style of subsequent films. This is particularly pronounced in the crime sagas that were largely made possible in the first place by Coppola rather than Scorsese: many things about making movies changed in that time. De Palma’s comically drug-fueled grotesquerie in Scarface serves as a potentially useful benchmark for when the last traces of the studio system’s penchant for restraint really disappeared when it came to previously taboo levels of violence in films. The Coppola-Willis approach was more rooted in noir or Universal Horror — the restrained approach of the Hays Code, without the censorship.

Also troubling the waters when it comes to parsing the influence of The Godfather is Part II, which somehow managed to do it all over again, and Part III, which did not. (Part III coming out the same year as Goodfellas is an amusing fluke of timing, particularly in the wake of Coppola initially wanting Scorsese to take over Part II.) They arguably function more as extended denouements to the original, and their opening celebration scenes mark out their differences: the authentic Italian wedding of the first film turns into a nouveau riche affair pandering to tasteless WASPs in the second, and a desperate attempt to recapture the old culture in the third. (Based on the openings, Talia Shire’s Connie is the secret heroine.) Where the original was a descent into unwarranted ambivalence toward evil deeds, Part II wallows in it and Part III seems to pause when the ends — presumably justified by the means — don’t pan out as intended. The flashbacks in Part II are mostly focused on Vito’s rise, but the announcement of Michael joining the military that concludes the film is the closest Coppola ever comes to directly tackling whether Michael’s decision to run the family in The Godfather was just him trading in one form of institutionalized killing for another.

The arc of The Godfather movies is long and Coppola’s career is longer, but it’s a body of work that lends itself very easily to discussions of how artists need to chase whatever sources of money they can scrounge up, even if the project seems inherently corrupt or the book it’s based on is bad. (This doesn’t even factor in The Godfather’s notoriously troubled production, which tends to be under-discussed by virtue of how Coppola had even more infamously brutal filming days ahead of him.) Coppola’s transfiguration of The Godfather from being “one for them” into “one for me” has to be the single most successful example in American cinema of giving (almost) everyone what they want from a movie, and it has kept his career going for another 50 years. It may have felt like a poisoned chalice when the public couldn’t get on board with films in the vein of One From the Heart, and millions were burned up as a result, but who’s to say that poisoned chalices can’t also be Holy Grails?

Published as part of Francis Ford Coppola: As Big As Possible.

Comments are closed.