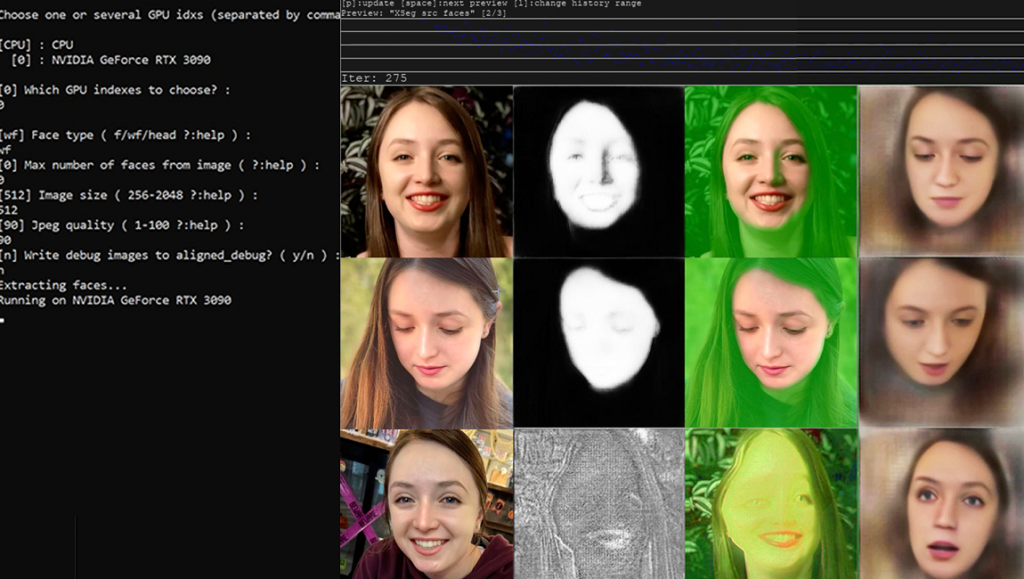

A sobering reminder of the minefield the Internet can be for women, the documentary Another Body, from filmmakers Sophie Compton and Reuben Hamlyn, is perhaps one of the more unnerving recent examples of form being shaped by subject matter. We’re introduced to college-aged engineering student “Taylor.” “Taylor” is ambitious, academically accomplished, and outwardly happy until one day she learns from an apologetic male friend that there is a video on a popular porn website which appears to feature her engaged in an explicit sexual act. “Taylor” is mortified to discover that the video is not actually her but is a deepfake. For those blessedly unfamiliar with the term, deepfakes are a controversial form of video where, using commercially available software and A.I., “regular people” (although, boy, is that a relative term) are able to create photorealistic, full-motion facsimiles of human beings appearing to say and do things that they otherwise never would. Alarm bells first sounded about this technology years ago, primarily in anticipation of it being employed to spread disinformation and potentially swing elections (Jordan Peele even made a PSA on the subject back in 2018 which made convincing use of his Obama impersonation). However, as with all emergent technology, it’s primarily been applied toward pornography. More specifically, creating reasonably convincing video clips where everyone from movie stars to politicians to amateur citizens can have their faces nonconsensually imposed upon porn actors, at which point the videos are uploaded online and viewed by millions of people.

This may be the appropriate place to discuss Compton and Hamlyn’s fascinating, if not entirely successful, formal gambit (as well as dispense with at least some of the scare quotes). As you can probably infer, the woman at the story’s center is not really named Taylor, and the school she claims to be attending isn’t real either. But, in what is either a commendable attempt to preserve the anonymity of its subject or a chilling glimpse into a post-truth future, the filmmakers have taken the remarkable step of creating a deepfake of Taylor, hiring an actor whose face has been mapped and placed onto her body for the entire film. And it’s not just for her either. As Taylor attempts to make sense of how this happened and who might be responsible for the videos (we learn there are a ton of deepfakes featuring her), she identifies female classmates subjected to the same violation of their privacy, including a young woman identified as Julia who’s similarly obscured by a benevolent deep fake. Further, in a rather extraordinary step, the film fabricates countless innocuous snapshots of unwitting women, as well as more insidious deepfake porn videos featuring our deep fake actors, blurring out the more graphic elements, then populating them on staged 4chan threads and Pornhub accounts in order to convey the pervasiveness of the issue. The film wouldn’t be the first documentary to go to extreme lengths to obscure the appearance of its subjects (2020’s Welcome to Chechnya also used AI to disguise its interviewees, although it purposely called attention to itself more), but this feels like an especially bold, if troubling, application of the technology.

It all falls just on the believable side of the uncanny valley, but it’s unsettling all the same. As a proof of concept of just how convincing deepfakes can appear to the casual viewer, it passes with flying colors, only inviting scrutiny with the occasional visual distortion (the technology seems to work best with limited mobility, which is less of an issue in a talking head format). But there’s something undeniably dead-eyed in Taylor’s otherwise forceful yet warm delivery; perceptible as “off” yet difficult to put your finger on why even before the film comes clean about what it’s doing around the 15-minute mark. Further, it’s slightly unseemly going to these lengths, in essence creating deepfake pornography (albeit presumably with the consent of all parties involved) just to make the argument for how pervasive it is. It’s not necessarily a question of “ethics” — which itself is a loaded term, historically bandied about in bad faith as an excuse to attack women on the Internet — but it does raise the question of what, if anything, we’re seeing on screen is actually “real.”

Having found one another, Taylor and Julia share notes and collaborate on an informal investigation into who might have done this to them. The bulk of the film takes the form of a two-way video chat, capturing their disgusted reactions to each new discovery in real time, all while trying to comprehend why someone would do this. After wading into the cesspool of deepfake porn sites and message boards, they come to the conclusion that the offending party is a former male roommate of Taylor’s (this individual, like the women in the film, is granted anonymity and given an avatar which conceals his actual face) who they had a falling out with years earlier. In an all too familiar turn of events, this individual allegedly lashed out over perceived emotional rejection, acting on his grievances — imagined or otherwise — by attempting to humiliate an innocent woman. It’s a narrative often associated with revenge porn, but as the film makes maddeningly clear, the laws about deepfakes are so nascent that there may not actually be criminal recourse for victims — the film presents a phone call between Taylor and her local police dispatch, with the officer taking the call at an utter loss as to whether a crime has been committed or how even to proceed investigating it.

We’re ultimately left in a disquieting and unsatisfying place where comeuppances are in short supply and happy endings are measured. The sense of violation for the young women is palpable and, as the film briefly argues, these attacks against women are primarily a means of cowing them into compliance or forcing them off the Internet altogether. But beyond the justifiable sense of being skeeved-out, it’s uncertain what’s actually to be done to stop this sort of thing (it’s telling that no one in the film even mentions the phrase “First Amendment”). In addition, the filmmakers may have only further muddied the waters on the pliability of ostensibly documentary footage, opening the door for far more nefarious applications. You may want to take a shower after watching this — for more than one reason.

DIRECTOR: Sophie Compton, Reuben Hamlyn; CAST: Ava Breuer, Faith Quinn; DISTRIBUTOR: Utopia; IN THEATERS: October 20; RUNTIME: 1 hr. 20 min.

Published as part of InRO Weekly — Volume 1, Issue 11.

Comments are closed.