Will Ferrell is a very funny guy who has been accused of doing a certain type, a type he falls into easily, too often. I prefer to think of his as a coherent body of work. Whether macho man or milquetoast, Ferrell’s characters are tied to each other by the carefully-arranged and precise lives they lead, and by their adverse reaction to shifts in those lives. The slightest upset can send them off into fits of howling anger or surrealistic verbiage. The man’s hallmark is a barely concealed rage; what sets his fury apart from that of his former SNL castmate Adam Sandler is that his is an ineffectual one. When cut loose, Ferrell’s flailings provide nothing more than an embarrassing release valve, and it’s this disconnect between the intent and the effect that equals comic gold.

The Other Guys, Ferrell’s latest collaboration with writer/director Adam McKay, is a strong vehicle for Ferrell in that it thrives on the comedic possibilities of that dichotomy, of the space between the unassuming and the uncontrolled. The titular pairing, indeed, is a stereotypical Odd Couple set-up, with Ferrell as the meek, proud desk jockey and Mark Wahlberg as his frustrated, seething hotshot of a partner. They, like their co-workers, live in the shadow of cock-of-the-walk action heroes, celebrity cops of the precinct. Played by Samuel L. Jackson & Dwayne Johnson, these two get the glory and the thrill of tearing apart city blocks to catch perps while Ferrell and Wahlberg are left to shuffle the paperwork necessitated by the former pair’s extravagantly destructive shenanigans. Ferrell couldn’t be happier about this, and his contentment further aggravates Wahlberg’s caged alpha male.

This basic clash of contrasting personalities leads to a number of explosively funny moments: I knew the film had me helpless in its grasp when, after Wahlberg vents at Ferrell, the latter fires back unexpectedly with a long, increasingly deranged monologue about the dangerous nature of tuna fish. Already, the framework of a mismatched buddy-cop comedy from the ‘80s is evident, with Wahlberg as the fuming straight man and Ferrell as the quirky main attraction. Kevin Smith’s Cop Out covered a good deal of this ground earlier this year, but where the affectionate joshery of that film made it feel like the genuine article, The Other Guys makes no bones about being foremost a genre piss-take. If it indulges in the conventions of the buddy-cop genre, it’s only to tweak them for maximum hilarity—even the action-heavy climax is somewhat deflated of its bombastic nature by sidelong chuckles and absurd touches (i.e. the lunatic indestructibility of Ferrell’s Prius).

The film also benefits from a terrifically game cast. Jackson and Johnson breeze through with a knowingly brazen arrogance signifying that they’re The Heroes, Goddammit. Plus there’s Michael Keaton stealing damn near every scene his pressure-cooker police chief appears in. Eva Mendes, Ray Stevenson and (especially) Steve Coogan also offer worthwhile support in their respective roles. But it’s the Ferrell/Wahlberg show for much of the way. Where Cop Out was a genre film with aspirations towards comedy, The Other Guys is a whacked-out collection of Ferrell/McKay randomness formed around the loose idea of a buddy-cop genre film. For every gag or running joke that doesn’t work (Wahlberg’s fateful encounter during the World Series is a half-hearted idea that gets pounded into nothing), there’s a goofball set-up/payoff to balance it out. (Two words: “soup kitchen.”)

The Other Guys is ultimately a paean to the nameless working man, but it’s also a grenade tossed at the fellows who spent a number of years robbing us blind and the society that, in essence, allowed them to do so by paying them no mind.

During one of the aforementioned paper trail orgies, in the aftermath of a daring, acrobatic jewel robbery that results in a couple unexpected fatalities, Ferrell discovers a building-permit infraction traceable to a weaselly high-roller played with perfect flopsweat unctuousness by Coogan. As the rest of the force attempts to crack the higher-profile case, Ferrell and Wahlberg find that there are deeper and darker currents running through the seemingly innocuous misdemeanor they’re pursuing. As the case evolves, so does their relationship, which naturally leads to ever-more-surprising angles from which the funny can burst out. Wahlberg softens to reveal a wounded heart and taps his rarely-seen reserve of aggro comedic energy—his sudden display of balletic skill as a response to a slight from an ex-lover is a highlight, as is Ferrell’s incredulous reaction (“You learned sarcastically?”).

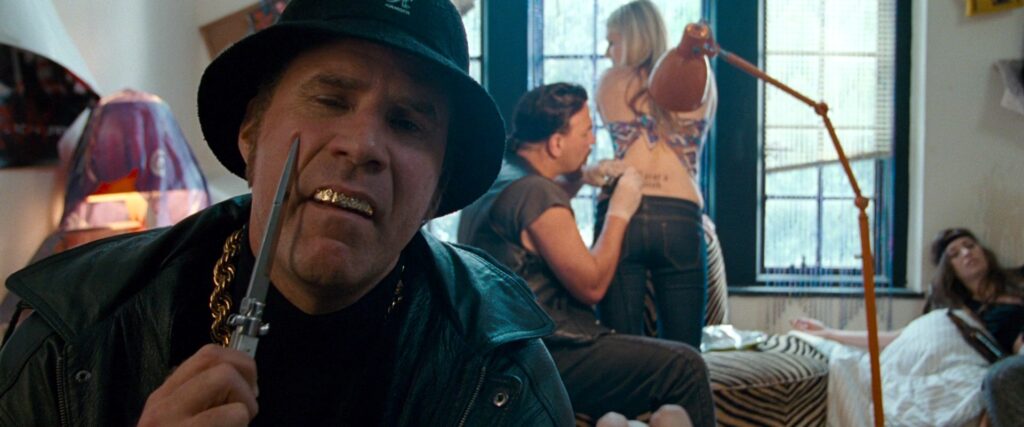

And where Wahlberg loosens up, Ferrell gets more jagged and allows the anger within to sputter out in manic blasts of bizarre ferocity, mainly via his suppressed alter ego—a loud, half-deranged pimp named Gator. (There’s a certain kind of glee in witnessing a spastic Ferrell bellowing “Gator wants his gat, you punk bitch!” at a surprised Michael Keaton.) As their relationship evolves, so does the film. But there’s another kind of push-pull tension under the surface. The third act downplays the comedy in favor of a car-chase-and-Mexican-standoff-style climax, and while the laughs are still there (Coogan’s running commentary during the car chase part is a delight), the more aggressive nature of action cinema leads to some of the script’s darker impulses amassing themselves.

The longer The Other Guys runs, the clearer it becomes that there’s more to the film than mere silliness. Step Brothers, the last McKay/Ferrell project, though uneven, betrayed a source for the random ejaculations of fury and hostility that mark their work together thus far: a sense of being marginalized, looked over, forcibly assimilated by The System at the cost of individuality. The Other Guys furthers that picture: Living a lifetime of mediocrity isn’t so terrible, but what makes it terrible is constantly being shat on by those who’ve risen above the average while you yourself are forced to scramble to make ends meet in relative anonymity. The flashy, the violent and the stylish distract attention spans, but it’s the guy you aren’t expecting and aren’t paying attention to—the guy who’ll tell you everything’s running smoothly—who will cut your legs out right from under you.

So The Other Guys is ultimately a paean to the nameless working man, but it’s also a grenade tossed at the fellows who spent a number of years robbing us blind and the society that, in essence, allowed them to do so by paying them no mind. It’s a long road from the early lightweight hilarity of The Other Guys to the cover of “Maggie’s Farm” by Rage Against the Machine and series of graphs about the 2008 financial crisis that make-up the film’s end-credits, yet the progression makes a surprising amount of sense. The Other Guys, like Ferrell, conceals in its heart a chaotic and terrifying anger, but unlike its star, it releases it slowly and steadily, until the thrust of its ultimate message is impossible to miss: We’re all The Other Guys, and that should piss you right the fuck off.