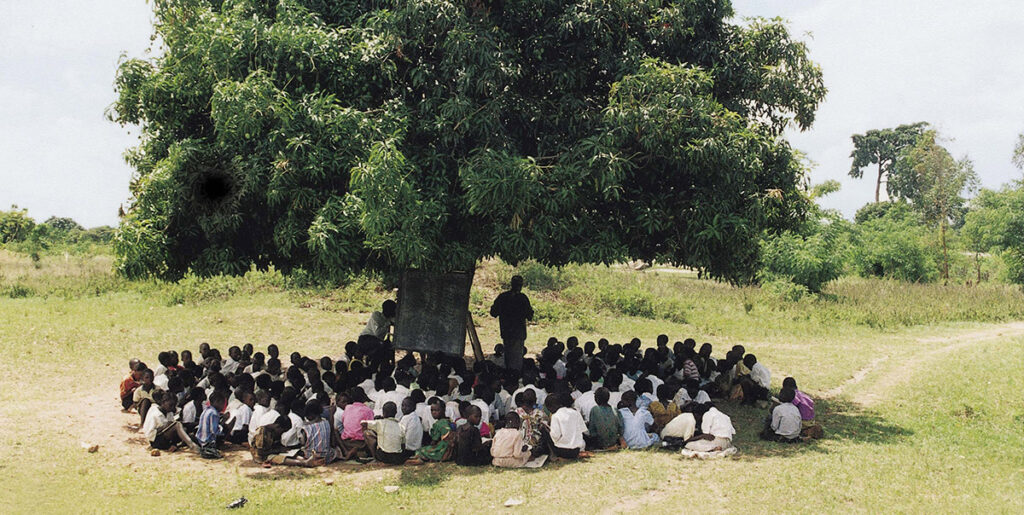

In 2001, at the request of the United Nations, Abbas Kiarostami traveled to Africa to scout locations and shoot raw footage for a film focussing on the lives of Ugandan orphans. His previous experience working with children made him the perfect candidate to work with these new subjects, and arming himself with a digital video camera, he recorded ten days of footage, capturing the harsh realities and amazing strengths of a people struggling to survive in a world with little opportunity. The resulting film, ABC Africa, is both heartbreaking and hopeful; without manipulation, Kiarostami communicates the depths of tragedy millions of orphans face, helpless to the ravages of war and AIDS. The filmmaker’s straightforward, first-person approach pushes documentary form beyond objective journalism, into a captivating and unique humanism. In the face of death, Kiarostami celebrates life—scenes of children playing, singing and dancing—to remind us that this is a story about real people who aren’t merely victims of tragedy, or images from a TV advertisement. Few filmmakers would have the control and vision to take such an uplifting perspective toward this depressing subject. Kiarostami’s free-flowing structure gives the impression that we’re just ‘along for the ride’ as he discovers the unique rhythms and rituals of this new world he’s found himself in. And, in reality, that’s exactly what’s happening here: what we see on screen is Kiarostami uncovering the layers of this culture in real time; he literally wanders the streets, shooting what’s before him, and we never know what’s going to be around a corner or through a doorway—likewise, neither does he. It’s thrilling and unsettling throughout, and at times, downright brutal: images of sick children are never easy to endure and Kiarostami doesn’t turn away or make it easy for us. He wants to make sure the truth resonates, and to his credit, he frames and presents his most unsettling images through a lens of curiosity and inquiry, rather than exploiting or gawking at them. It helps that Kiarosatami often appears in the frame, interacting with kids, inserting himself into the situations and making it clear that he is personally invested in his subject. It also helps that extreme misfortune is contrasted by interviews with government workers, who assert their focus on protecting these deserted children through various social programs, especially highlighting Uganda’s progressive attitude toward AIDS prevention. With little more than his hand-held camera, Kiarosatami captures the heart and soul of his chosen location, providing context for the horrific epidemic that surrounds him. Whether observing the action from a distance in a moving car or up way too close at a health clinic, the director brilliantly captures the physical and emotional experience of being at that place in that moment. In one especially memorable sequence, the electricity goes out in a building but the camera continues to roll. We sit in the dark for at least five minutes listening to conversations (the only visual element being subtitles) and other sounds, without the benefit of light. For many filmmakers this sequence would have wound up on the cutting room floor, an inconvenient mistake with no value. For Kiarostami, moments like these are at the heart of his quest to bring truth and understanding to his audience by any means necessary. While the subject matter of ABC Africa may not be everyone’s ideal viewing, the filmmaking is stunning in its minimalism, and amazing to behold. Aspiring filmmakers and students of film will be hard pressed to find a better example of what good man and his camera can achieve.

Comments are closed.