The daughter of Minos and wife of Theseus has long fascinated many a romantic soul — Euripides, Racine, Swinburne, and Lee Hazlewood all wove the name of Phaedra into their offerings (Hazlewood via the 1967 Nancy Sinatra-aided schlock classic “Some Velvet Morning”). Edgar Froese’s reasons for naming West Berlin synth outfit Tangerine Dream’s fifth album after the Greek figure seem altogether casual: “We’ve always been interested in Greek mythology,” he shrugged, “and the titles on [Phaedra] come from there. Not just Greek, but Egyptian, Indian, European philosophy mixed with a bit of humor.” Ah, yes, that famed TD sense of humor, best exemplified here courtesy of knee-slapper “Mysterious Semblance at the Strand of Nightmares.” Or perhaps the joke is how randomly Froese plucked a name from Greek mythology, one quick act of cultural appropriation on the way towards producing one of the more abstract albums to ever go gold (#15 UK charts, broke Top 200 in the more prog-wary US). Sitting midway between Froese’s earlier, more clangorous experiments in end-stage psychedelia and TD’s late seventies dive into movie soundtrack cheese, Phaedra marked a clean break from the so-called Pink Years — the plink-plonk krautrock of Electronic Meditation, the tentative Kosmische of Alpha Centauri, and the interplanetary dialogues of Zeit and Atem. Those Mellotron-drenched excursions into dark matter did their Teutonic best to avoid melody and all but the barest of rhythmic patterns, the better to approach the yawning analog abyss. Phaedra was TD’s sellout move, jumping from the tiny Ohr label to the UK’s expanding Virgin Records, proud home to Michael Oldfield’s prog-kitsch million-seller Tubular Bells, a label boasting the kind of promotional muscle and distributive power that could push a wordless four-part suite of electronic bloops and bleeps into six-figure sales even minus support of radio play, aside from that offered by dear old John Peel.

Decades on, Phaedra still demands and rewards your patience.

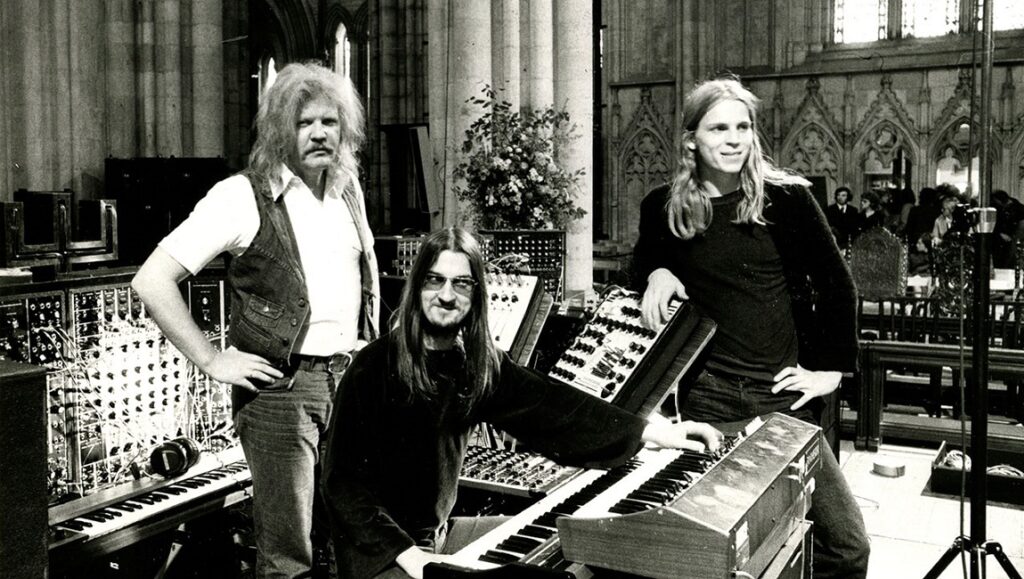

Now down to the trio of Froese, Peter Baumann, and Christopher Franke, TD managed to hang on to vestiges of their earlier sound — Baumann’s flute surfaces in brief album closer “Sequent C,” while the Zeit-like Mellotron grandeur of an essentially solo Froese track opens side two. But there’s plenty of supporting evidence that Froese and co. did indeed blow Virgin’s healthy advance on a brand new Moog Modular synthesizer, a fun new toy to be placed alongside TD’s preferred portable analog synth, the EMS VCS 3. These synths were smaller and cheaper than their ENIAC-sized precursors, and while they may have introduced new levels of chaos into the recording studio (tape snaps, console meltdowns, low-frequency cock ups), their presence also meant a wider array of noises and greater flexibility in touring, and helped introduce the so-called Berlin School sound of Tangerine Dream Mach II, i.e., oscillation oscillation oscillation. And while still light years behind the electro-funk explorations of such Dusseldorf peers as Kraftwerk and Cluster, Phaedra allowed TD the chance to incorporate synthesized rhythms into their sonic landscapes for the first time, from Moog burps sequenced into fluttering patterns to ring modulators helping approximate the psycho-acoustic shimmer of Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians. True, Phaedra is far cornier than Reich’s eventual triumph of minimalism, with Froese’s sighs and squiggles pointing the way towards the gaseous likes of Jean-Michael Jarre rather than Brian Eno’s at-home installation pieces. Yet pretension aided by technological advances will always be the dodgiest of experiments. Prog rarely handled itself with Froese’s level of masterful detachment. Decades on, Phaedra still demands and rewards your patience.

Part of Kicking the Canon – The Album Canon.

Comments are closed.