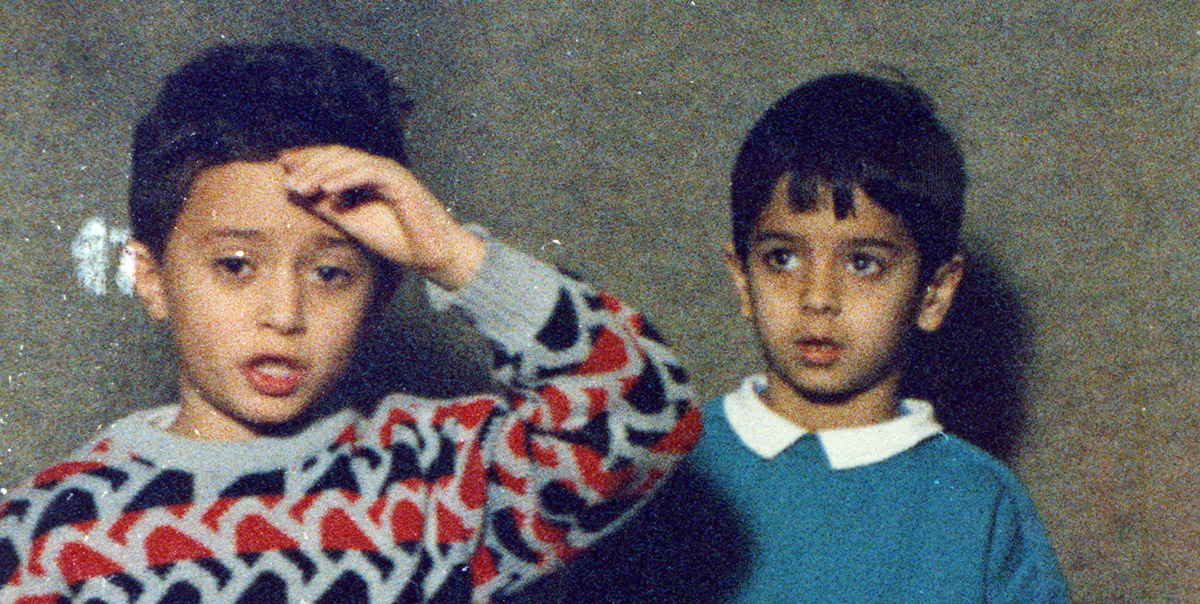

“Things repeat themselves with differences I can’t understand,” proclaims Oki (Jung Yu-mi), the director of the fourth, and final, film-within-the-film that comprises Hong Sang-soo’s 2012 feature Oki’s Movie. She has attempted to compare and contrast two relationships that she had — one with a professor (Mun Seong-kun), one with a fellow student (Lee Seon-gyun) — by casting actors who look similar to the men that she knew, and then following them on separate dates, walking up the same mountain, one year apart. But the experiment hasn’t worked; it’s too close to reality, and yet not close enough. She concludes, “The limits of the resemblance… reduce the effect of the two put together.”

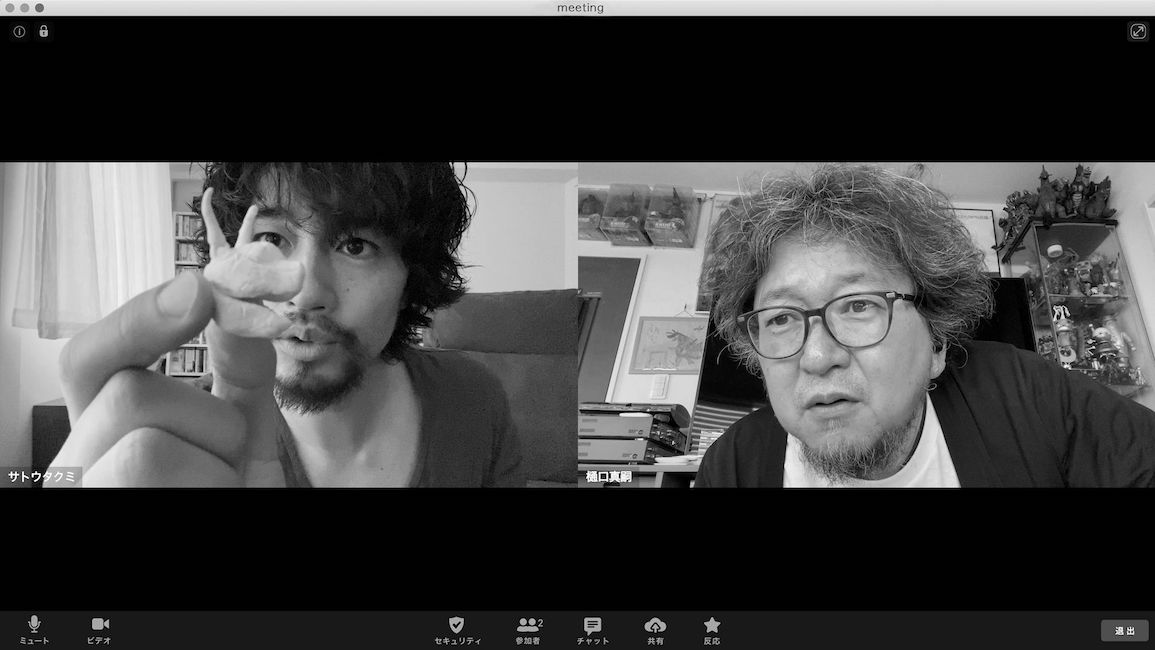

Oki’s Movie is made-up of four mini-films. The first is about Nam Jin-gu (Lee), a film director — and touches on an unsatisfactory married life, attempts to date a current student, a fraught relationship with colleagues, and an awkward confrontation during an audience Q & A for one of his films. The final three parts may, in fact, be intended to be films made by Nam — an attempt to understand the love triangle that he’s found himself in, with each showing the perspective of one of the people involved.

It’s not by being completely true to life that a director best expresses the truth, but rather it’s by submitting reality to formal constraints.

Nam casts himself as a romantic hero in the first film: obsessed, drunk, but ultimately winning. In the second, Nam’s mentor, Professor Song (Mun), imagines himself wise and profound, offering pithy witticisms in a Q & A session (“In life. . . of all the important things I do, there’s none I know the reason for“). The third film, though, belongs to Oki — and it’s here where the experiment finally breaks down, as the director (Oki ostensibly, but it might also be Nam) realizes that art is not a substitute for real life.

In the first film, Nam advises one of his students on how to improve her screenplay: “Your sincerity needs its own form. The form will take you to the truth. Telling it as it is won’t get you there. That’s a big mistake.” The student accuses Nam of trying to impose a formal structure on her film out of greed, to make it more palatable to a mass audience — an accusation that Nam responds to with anger, declaring that the form (“two turning points!”) is actually how she can “take away what’s fake.” It’s not by being completely true to life that a director best expresses the truth, but rather it’s by submitting reality to formal constraints. Oki will realize this — that she made a mistake in trying to just tell it like it is.