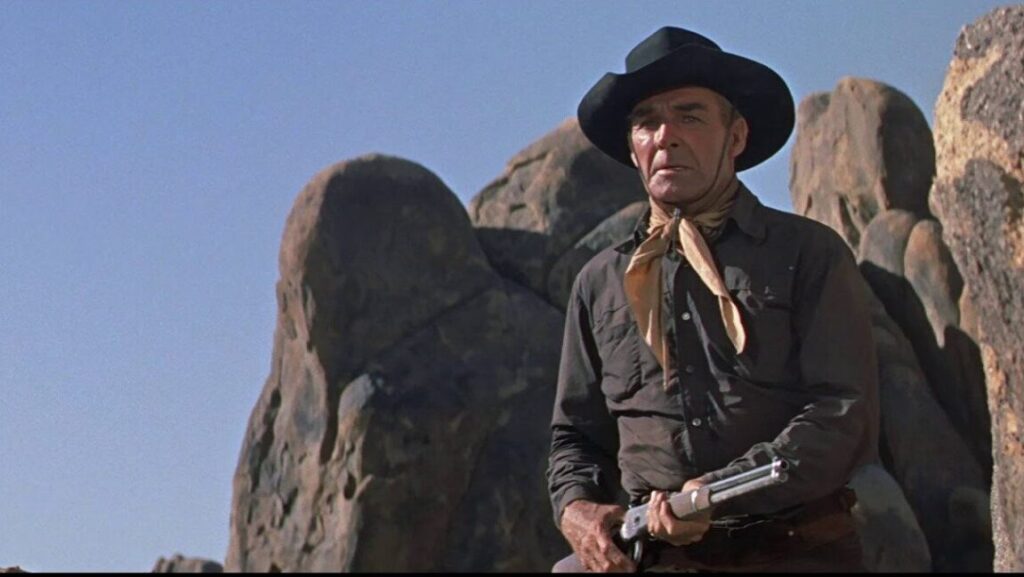

The decade of the Great Depression saw a slump in high-end Western productions. This indigenous genre had been immensely popular with audiences of the two previous decades yet became relegated to a genus of the ‘B’ movie with the advent of sound. Randolph Scott started his vocation in Westerns during this period, starring mostly in low-budget adaptations of Zane Grey novels; finally, in ’36, he moved up to ‘A’ productions, with the genre itself in close pursuit. Scott would go on to be directed by such names as Henry King, Fritz Lang, and Allan Dwan, but it wasn’t until the final years of his acting career that he’d star in the films that perhaps left the greatest mark. Though only modestly successful in America at the time, this series of films, later dubbed the Ranown cycle, would slowly find a wider audience — as well as much a deserved critical reappraisal. None of these films bear any plot connection, and the production company after which the series is named was only involved in five of them; regardless, the ‘Ranown’ title is typically seen as synonymous with all six of the Scott and Budd Boetticher collaborations that were written by Burt Kennedy (the outlying, and comparatively minor, seventh, Westbound, lacked the writer’s input). Comanche Station was the film that drew this fruitful alliance to a close: Scott again plays a lonely wanderer, Jefferson Cody, who’s forced into conflict against outlaws in order to save a woman. Cody bargains for the release of a Mrs Lowe (Nancy Gates), whose stagecoach was raided by Comanche. On their way back to Mrs. Lowe’s husband, they’re joined by three outlaws, one of whom — the leader, Ben Lane (Claude Akins) — holds a grudge against Cody, who had him court-martialed for killing Indians. Ben subsequently plots to kill Cody and himself claim the $5,000 dead-or-alive reward for rescuing Mrs Lowe.

This, and some of the other Ranown films, offer a kind of anamnesis for a genre that had grown bloated and fussily self-reflexive — obsessed with the national myth.

Like the other Ranown entries, we see here the masculine being invoked by (and therefore revolving around) conflict intrinsic to the female presence in such a space. Cody and Ben signify two alternate representations of masculinity, diverging in their capacity for righteous thinking and purposeful actions. Between these two are Frank (Skip Homeier) and Dobie (Richard Rust), the other members of Ben’s gang, who find themselves questioning orders. Frank’s reflection on his father’s wish that he should “amount to something” directs the two away from the pseudo-family structure that Ben’s gang provides and attracts them to the greater purpose embodied by Cody’s resolute individuality. Though Cody’s and Ben’s paths have been ordained, we see Dobie and Frank’s reasoning exposing to them their function within the outlaw group as well as the moral ramifications of their potential actions. By the end, Frank is ironically unable to bring to fruition a newfound cognizance of virtuousness, due to his early death (ironic considering it was he who first laid doubt on Ben’s actions). Dobie, however, discovers redemption in his final gesture: Mirroring the attitude of Frank’s statement that “a man does one thing in his life he can look back on,” Dobie warns Cody of Ben’s trap and sacrifices his own life. This kind of moral underpinning, in conjunction with Scott’s stoic and assertive heroism, seemingly harks back to the days where a protagonist would ride off into the distance before he’d even received his reward — which is exactly what happens here. In retrospect, this, and some of the other Ranown films, offer a kind of anamnesis for a genre that had grown bloated and fussily self-reflexive — obsessed with the national myth. Paring-off extraneous elements, Boetticher focuses on somewhat austere storytelling and moral certitude, so as to stand out within the context of this genre’s history.

Part of Kicking the Canon – The Film Canon.

Comments are closed.