From our Honorable Mentions post: It goes without saying that 2020 was a year like none other in recent history. Significantly, by virtue of living through such times, it’s also a year that retuned minds to see history being made in the present. There are certainly more critical sociocultural institutions whose shape have been permanently altered, but in a year where entertainment was sought (and was, arguably, psychologically essential) more than ever, the film industry’s struggles played out on a grand stage. Streaming services boomed — the less said about Quibi, the better, but TV mainstays like Hulu and HBO Max became major players in the feature film game, the latter especially, with its massive late-year Warner Brothers deal — while theaters remain on life support, and drive-ins boasted an unexpected return to relevance. But the actual slate of films released didn’t bear out the same direness: in the absence of tentpoles and endless money-grubbing sequels (mostly; remember when that new Bill & Ted flick snuck out?), plenty of wonderful art was made available to grace our TV and laptop screens. Not reliant on a huge box office, a number of international auteurs found their latest titles given official 2020 releases in virtual cinemas, if they hadn’t already snuck into theaters in the year’s first couple months, and many reflected the directors’ best work in years (Pedro Costa, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, and even a long-held Hong Sang-soo film). Micro-budget cinema thrived (Fourteen, The Vast of Night), Netflix remained a welcoming platform for visionaries (Spike Lee, Charlie Kaufman), and major film experiments saw the light of day (Small Axe, half of DAU). It’s impossible to know what exactly the film industry will look like in a post-COVID world, but if this is to be the end, it could’ve been worse — we were at least gifted some good flicks on our way out. Luke Gorham

Below are the films we rated 11-25 in our annual poll, with some of the pieces excerpted from positive takes we published throughout the year and others newly written for Best Of commemoration. The point is, we like them. If you haven’t, give them a chance.

Credit: NYFF

25. On the Rocks

[Sofia] Coppola’s movies are frequently sort of hermetic dreams, but On the Rocks feels like the work of someone trying to understand all the ways that their bubble has been pierced by the simple daily work of life. You can look at it as a more settled-down version of the comeuppance delivered at the end of Marie Antoinette or The Bling Ring. And certainly the dissatisfied spouse on a semi-spiritual trip through the big city with a dry-witted gentleman bandit can’t help but recall Lost in Translation. But the closest comparison is really Somewhere. In contrast to that film’s decadent Los Angeles, Chateau Marmont setting, the New York City of On the Rocks is one of quiet nostalgia and warm comfort, though fittingly both films are stories of loyal (possibly to a fault) daughters contending with part-time dads. Felix’s talk of what men and women want echoes the young girl in Somewhere coming to grips with what she’s learning about what men expect of her and where she’s learning those expectations. Laura’s vague dissatisfaction with her marriage (but not just her marriage) is the same existential angst of the Hollywood star who just wants to dip out. Coppola reconfigures all of these pet themes — and her open admission of the comfort of her privilege, here in the obvious semi-autobiography brought by [Rashida] Jones (daughter of Quincy) and [Bill] Murray (totally playing into his persona as a superstar self-absorbed goof) — into a sort of sedate screwball comedy of errors. Missed opportunities and mistaken assumptions abound, as you’d expect, but the aim isn’t a raucous pace or a belly laugh. The jokes here are played for sympathy rather than irony, and who better to sympathize with these people than this cast and director? In the end, they’re all just more settled now. A little older, hopefully smarter, and probably not as cool as [they] used to be (well, except Murray). So when Laura side-eyes Felix’s patented traffic-cop schmoozing, of course he replies “I wouldn’t have it any other way.” Matt Lynch [Excerpted from full review.]

Credit: Cannes Film Festival

24. The Wild Goose Lake

There’s a particularly pleasing synesthetic joy to watching a movie that values style as much as substance; Drive’s shimmering neon palate immediately comes to mind, as does the languid magical realism of Bi Gan’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night. In addition to aesthetics, these two films share certain narrative sensibilities with Chinese director Diao Yinan’s The Wild Goose Lake. […] The Wild Goose Lake is essentially a manhunt thriller (perhaps the transliterated title is meant to be a pun?), and its characters’ bleak circumstances are a stand-in for the social ills that got them there in the first place. American noir tradition is imbued with post-war fatalism, a cynical hangover from the Great Depression. Here, Yinan’s pessimism skews in the other direction: his focus is the degradation, seediness, and hard-won grit of a country whose fabulous economic success is built on the backs of third-bit criminals, beachfront prostitutes, and laughably corrupt policemen who have no problem posing for photos with a corpse. […] In one vivid, playfully gruesome scene, a villain wielding a knife is defeated by the antihero’s translucent plastic parasol. Yinan’s wholly unexpected use of this object, which is utterly ubiquitous throughout China and Chinatowns the world over, is a succinct encapsulation of the movie at large: he confidently deploys familiar noir tropes alongside everyday hallmarks of contemporary Chinese culture. In another scene, a group of nighttime plaza dancers – another thoroughly unremarkable sight – is infiltrated by gangsters, and in the ensuing showdown, their light-up LED soles suddenly turn The Wild Goose Lake into an extended Tron outtake. It’s not all style, of course. Liu Aiai, a “bathing beauty” of the eponymous lake, aids [main character] Zenong for reasons that remain ambiguously altruistic up until the final shot. Working the waterfront, she endures a multitude of casual and heart-wrenching violations with the resignation of a veteran. During one long take, she walks in front of a construction tarp printed with a rendering of gleaming glass towers and lush plazas. For a moment, a second-tier city morphs into a first, and her prospects rise accordingly. Then, the tarp ripples in the wind and Wild Goose lake reappears behind her. As it turns out, nothing has changed. Selina Lee [Excerpted from full review.]

Credit: Netflix

23. Dick Johnson is Dead

Documentarian Kirsten Johnson is magnificent at integrating certain presentational modes — montage, time capsules — into works of memory preservation. She reinterprets such a time capsule in Dick Johnson is Dead, depicting her 86-year-old father’s last moments with his family. Johnson begins her film with her octogenarian father, a retiring psychiatrist, departing his practice in Seattle to come live with his daughter, and watching the subsequent process of Dick Johnson’s loss of independence, and the burgeoning awareness of that development, is heartbreaking. Rather than either dehumanizing her father’s death or getting too kitschy with her particular cinematic form, Johnson intimately delineates her human subject, inviting the viewer into the family, so to speak. And if her latest isn’t as expansive as Cameraperson, understandable given its more limited scope, her technique here still reminds of the bouquet of images that compose that mosaic documentary. […] By proposing a litany of different demise scenarios, Johnson seeks to steal focus, therapeutically, from the struggles of her dementia-stricken father. In composing recreations of death — like bleeding out on the sidewalk after a construction incident — Johnson is acknowledging that, like anyone, her father could die at any given moment. In a sense, this is a blunt reminder that all life ends with death, but this extra comedic “relief” acts as balm for the pain both father and daughter are bearing as Dick reaches his final days. Meanwhile, the exploration of private rituals — things like inside jokes, unique memories, and remembrances of the deceased — that are shared adds an enriching texture to the Johnson family’s personal history. And so, if Dick Johnson is Dead fails to rise above time capsule cinema, built primarily to preserve the memory of the filmmaker’s father, it [remains] a charming and heartfelt portrait of a familial love. Patrick Devitt [Excerpted from full review.]

Credit: HBO Max

22. Let Them All Talk

If there is any affinity to be found between Steven Soderbergh and Olivier Assayas, it’s in their shared ability to turn the economics of filmmaking to their advantage, to leverage each project into a veritably Situationist endeavor — or, in other words, to recognize “the game on top of the game,” as Bill Duke puts things in High Flying Bird. In this respect, Let Them All Talk and Non-Fiction are the directors’ closest points of contact, each film using its book publishing milieu to craft a self-consciously modish comedy about the commodification of speech. For his part, Soderbergh convinced an accomplished fiction writer (Deborah Eisenberg) and a cast of seasoned pros (Meryl Streep, Candice Bergen, Dianne Wiest) to come onboard the Queen Mary 2 for a semi-improvised shoot across a single trans-Atlantic passage. The result is a marvelous (and marvelously photographed) comedy of inarticulateness, one that doesn’t just play on a writer’s stereotypical fear of speech (exemplified by Streep’s vapid, self-absorbed novelist, Alice Hughes), but also turns improvisational dead air into a virtue. The ocean liner setting further connects the film to a tradition of Hollywood cruise ship movies from One Way Passage to The Lady Eve, and thus to a long lineage of seafaring cons and pros. What Let Them All Talk understands, though, is that the eloquent, eminently literate hustlers that once populated those films — not to mention Soderbergh’s own work, from Out of Sight to the Oceans trilogy — are, in our data-driven present, a defunct class of criminal. Though once the glamorous backdrop of romance and adventure, the cruise ship is now just another outpost of neoliberal capitalism, where sparkling dialogue and elegant cons have been replaced by awkward probings, demeaning exchanges of business cards, and ersatz entertainment. In the age of the tell-all confessional, both words and personal relationships have lost their former value. Increasingly, every person knows they’re being played, plays accordingly, and just avoids talking about it. Ultimately, as at this film’s end, the winners are those who, consciously or not, avoid acknowledging that there’s a game to be played at all. Lawrence Garcia

Credit: IFC Films

21. Relic

Relic, the debut feature from Japanese-Australian director Natalie Erika James, is a haunted house drama with a thrillingly cerebral core. Edna, the family matriarch (Australian theater veteran Robyn Nevin), is prone to wandering and relies on post-it reminders scattered around her remote country house to function. After going missing for a brief spell, with no memory of her time away, her workaholic daughter Kay (Emily Mortimer) and teenage granddaughter Sam (Bella Heathcote) return home to watch over her until they can devise a plan. Despite its setting, Relic is far more astute than your standard haunted house flick. Within the walls of this perpetually dim and mold-ridden country estate floats an insidious, inescapable presence that we come to realize is Edna’s rapidly deteriorating mind. […] The home, as a traditionally feminine space, has long functioned as both a haven and a prison. Sam might know this instinctively, but it doesn’t stop her from offering to move in, tacitly situating herself as Edna’s protector and replacement. As the youngest, she’s sheltered by her age: she has no memories of spectral ancestors and no reason to ever consider her own mortality. Yet, in the film’s climactic third act, her youthful innocence is the perfect foil to her grandmother’s decaying mind. Trapped in a serpentine space devoid of reason, logic, or meaning, she experiences firsthand the meandering horror of Edna’s warped psyche. Her only escape is to smash through the walls, a moment of ingenuity that mirrors an earlier scene, when she crawled through a dog flap to unlock the front door from inside. If that scene is meant to evoke a birth of sorts, so too does Relic’s strange, poignant finale. Rather than shun the ghoulish, skeletal wreck that Edna has become, Kay instead cares for her, breaking the cycle of neglect that started with her great-grandfather. After gently stripping off layers of rotting skin, we see a small black creature that resembles a fetus or alien, aged but somehow innocent, even pure. Like the ending of Jonathan Glazer’s Under The Skin, a familiar but deeply unknowable being is excised and a dark inner core revealed — yet here, James opts for tenderness rather than violence, creation rather than destruction. This choice makes Sam’s final discovery all the more chilling. These women may have found a semblance of peace, but it comes at the expense of their bodies, minds, and possibly souls. Selina Lee [Excerpted from full review.]

Credit: Ai Weiwei Studio

20. CoroNation

The first 30 minutes of CoroNation, Ai Weiwei’s comprehensive snapshot of Wuhan, China in the earliest days of COVID-19’s global devastation, are among the most compelling put to screen this year. By focusing on ground-level human stories — in the opening moments, a couple trying to return home to the city after visiting family is met with police checks, hazmat suits, and governmental lockdown — the director effectively mixes horror, dystopia, and scientific procedural to build a tone of profound unsettlement. This beginning third is especially potent when considered after nearly a year of escalating tragedy and the normalization of protective measures, the early-days efforts at containment bearing the distinct character of science fiction in Ai’s hands; he supplements the close-quarters crises with floating aerial shots of deserted streets and a palette of grey dreariness reminiscent of Children of Men’s particular apocalyptic texture. Following this opening section, as CoroNation progresses, Ai expands the film’s focus and changes up his editing rhythms. The initial tone-setting — accomplished by weaving together concise, impressionistic scenes of confusion and complication with sequences of medical minutiae — gives way to prolonged, domestic-minded interludes that detail the human collateral of such bureaucratic domineering. Although not always expertly weighted or paced, this material is harrowing nonetheless, and the second half’s blunt shift is essential to Ai’s discursive, expansive portraiture, offering a number of profound entry points for considering COVID’s inceptive period. Much has been made of the production’s genesis — the film was edited together from over 700 hours of on-the-ground, often surreptitious footage submitted to Ai and his team — but this is no mere convenience for the Europe-dwelling director, nor is it a gimmick of any sort. The director’s use of such unofficial reportage offers a particularly fascinating opportunity for comparative analysis between Western approaches to the virus fight (particularly America’s bungled, capital-driven response) and China’s more masked strategy. But arguably as important is that this overall strategy also has an affecting congruity with another of the film’s chief concerns: capturing the small-scale tragedies that are lost within any means to an end. The power of CoroNation, then, is found in its multitudes; like any great work, the full scope of its complexity is impossible to contain in any single reading. Luke Gorham

Credit: Isiah Medina

19. Inventing the Future

What would it look like to adapt The Communist Manifesto to film? Thomas Paine’s Common Sense? Industrial Society and Its Future? These texts have no main characters to follow, no specific locations, and no visual action — they are texts anathema to a visual medium. So, when Verso Books first announced that Alex Williams and Nick Srnicek’s popular, radical pamphlet Inventing the Future would be adapted to film, suspicion rightly should have been raised. Instead, the announcement that Isiah Medina, director of the expressivist 88:88, would helm such a project helped make sense of the surprising announcement. Medina’s previous works often combined themes of technology and human intimacy — what’s immediately recalled are images of private texts between friends in 88:88 — so it’s no wonder that his filmic instincts and interests would work in tandem with such a text. Green screens, 3D animation models, phones, laptops, and video villages are usual symbols of cinematic capitalist excess for leftist critics, yet Medina’s Inventing the Future celebrates them in Eisensteinian montage. Tools that seem like such obvious symbols of subjugation are shown as mediators of relationships, realizers of large-scale imagination, and, most radically, instruments of play (shots of toys alluding to popular engineer-philosopher Reza Negarestani’s Intelligence and Spirit). Narration from the source material dominates the film, but Medina strays to corollary texts when appropriate — just how much this combination of text and image will make sense might depend less on how much one is paying attention than how much one can spiritually ride Medina’s argument-by-collage wave. This is not without controversy: Williams and Srnicek’s text decries “folk politics” of the left (think Occupy Wall Street, co-ops, local rallies) for not thinking as big as their enemies. Real power comes with the unwanted baggage of hierarchy and top-down initiatives that affect world-scale systems, a “Mont Pelerin of the left” in their words. That Williams and Srnieck have an earlier affiliation with “left-accelerationism” (notably a term not in Inventing the Future) that posits a neoliberal “collapse” event must happen before the left can rebuild its global society means that such a thesis will not be taken on faith. Medina’s film, then, fills in the aesthetic gaps by showing that such a tech-heavy world is desirable, that a world without work is enjoyable, and that we do love high-budget CGI entertainment so long as humanity is not lost in acquisitions and mergers. It certainly helps his argument that his film is free. Zach Lewis

Credit: TIFF

18. The Grand Bizarre

The first feature-length work from avant-garde filmmaker/animator/composer Jodie Mack defies easy categorization. The Grand Bizarre is a sort of musical (like her Yard Work Is Hard Work and Dusty Stacks of Mom) in that Mack’s rhythmic editing is synchronized with her original synth-pop score, which seamlessly integrates the ambient sound of machines, human voices, and wildlife. Grand Bizarre is also a landscape film, in which wide shots of scenic vistas around the world become staging areas for the stop-motion choreography of colorful fabrics, their geometric and floral patterns pirouetting and ping-ponging across the frame, or filling it in vibrant close-up. The film then becomes a strange kind of ethnography of labor, but one in which laborers themselves remain mostly out of sight, the shipping containers they move and looms they work lent a perpetual, dehumanized momentum by Mack’s animation of the 16mm images. The combined effect of her animation, the time-lapse photography, and the movement of natural elements such as wind, water, and the rise and fall of the sun captured within gives The Grand Bizarre a polyrhythmic dynamism. Mack’s cutting has rarely been so purposefully kinetic; the sequence where she rapidly edits together images of machines in a textile factory with the half-formed fabrics they’re weaving approaches a kind of analog glitch art. […] The viewer becomes especially aware of how the textiles are positioned and juxtaposed within the frame, at the end, when Mack slows down the pace and lets the sound of the winding Bolex become the soundtrack. Her work as filmmaker cataloguing and capturing these objects becomes part of the perpetual motion machine propelling them around the world, just as the montage that opened the film linked her travel in producing the film to that larger process. Alex Engquist [Excerpted from full review.]

Credit: Kino Lorber

17. Tommaso

[With Tommaso], the traits that define director Abel Ferrara’s best work are present and precise: the raw, low-key punk aesthetics; a mixture of the mundane and the otherworldly, the physical and the spiritual, the material and the mystical; the dissolution of reality into nightmares and dreams; and the expressive lighting which embodies a spatial and temporal purgatory. Further familiarity can be seen in the opening shot: Dafoe steps into the film to attend his Italian language class – the necessity of communication, verbal and physical, is another predominant aspect of Ferrara’s work – while the sound of church bells and heavy rays of light fill the screen, the crumbling facade and ancient columns of the building surrounding him. […] Ferrara dedicates a considerable part of Tommaso to an observance of everyday activities – domesticity seen in cooking and family dancing; the pleasures of meditation and lovemaking and shopping; the work of acting classes, rehab meetings, and Tommaso’s late-night, head-clearing wanderings – while his protagonist attempts to seek a way out of his created labyrinths of illusion and selfhood. His spiritual search dominates: in one hallucinatory scene, near the film’s end, Tommaso pulls out his heart and hands it to some black immigrants, while in another he crucifies himself in front of a crowd saddled with cellphone cameras (a reference to Dafoe’s performance in The Last Temptation of the Christ). And in between all this, Ferrara uses video clips as interludes to intensify the film’s emotional constructions of joy and melancholy. During a rehab session, Tommaso confesses his desire to remake Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, but Ferrara’s latest feels much more like his 8 ½, a deep reflection from an artist on his art and its genesis. It’s like Tommaso teaches in his acting class: “We’re just doing the action in a pure way. That’s when we get closer to experiencing, for me, the beauty of life.” Ayeen Forootan [Excerpted from full review.]

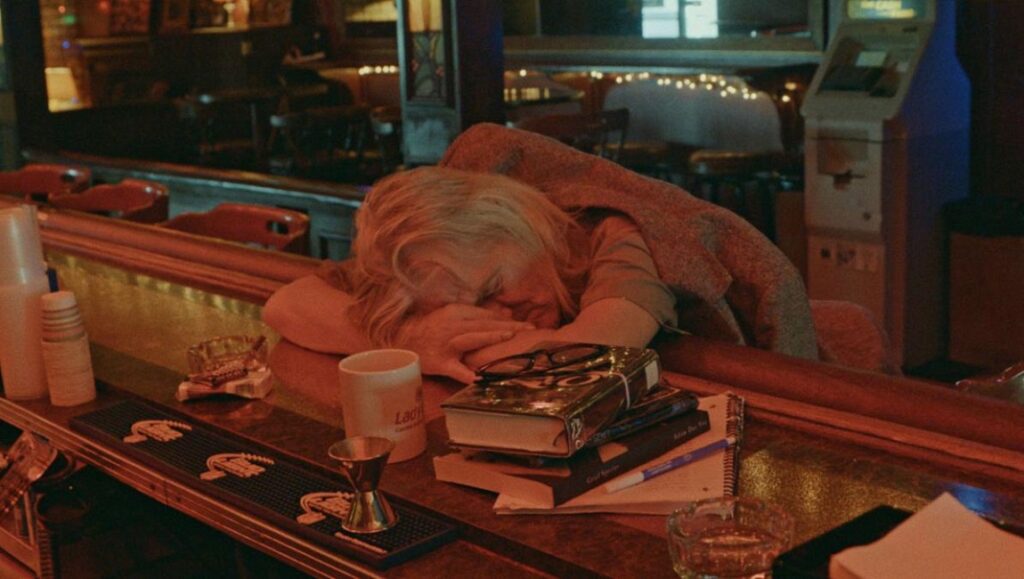

Credit: Department of Motion Pictures

16. Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets

An official selection of this year’s Sundance U.S. Documentary Competition, Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets chronicles the final business day of a Las Vegas dive, the Roaring 20s, where a group of regulars — mostly fast friends and familiar faces — gather for one last bibulous bash. Except the ostensible regulars are really strangers to each other (amateurs selected from various casting sessions at bars), the Roaring 20s isn’t closing, and the bar is actually located in New Orleans, the home base of directing duo Bill and Turner Ross. For the Ross brothers, then, the non-fiction categorization is more of a statement of intent, allowing them to thumb their noses at some of the more ill-conceived conceptions of the documentary/fiction dichotomy, while also acknowledging the self-imposed boundaries of their methodology. […] Bill Ross has said that their films are “really just about the images in our head,” a statement that’s borne out by the neon-soaked, hyper-clear digital of the main bar footage, the impressionistic Las Vegas interludes (shot with a Panasonic DVX100b), and the low-grade security camera footage of a scene involving fireworks. Even the closing credits, which include photos taken over the course of the shoot, highlight the project’s impressive visual range (no small accomplishment given the time-constrained shoot). Significantly, though, the Ross brothers’ formal adaptability does not at all obscure their way with character, and amidst the bar’s boozy chaos, the film manages to strike some genuinely touching chords. Towards the end, a regretful [patron] tells a young musician: “There is nothing more boring than someone who used to do stuff and just sits in a bar.” True enough, perhaps. For at least as long as Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets lasts, though, you may be convinced otherwise. Lawrence Garcia [Excerpted from full review.]

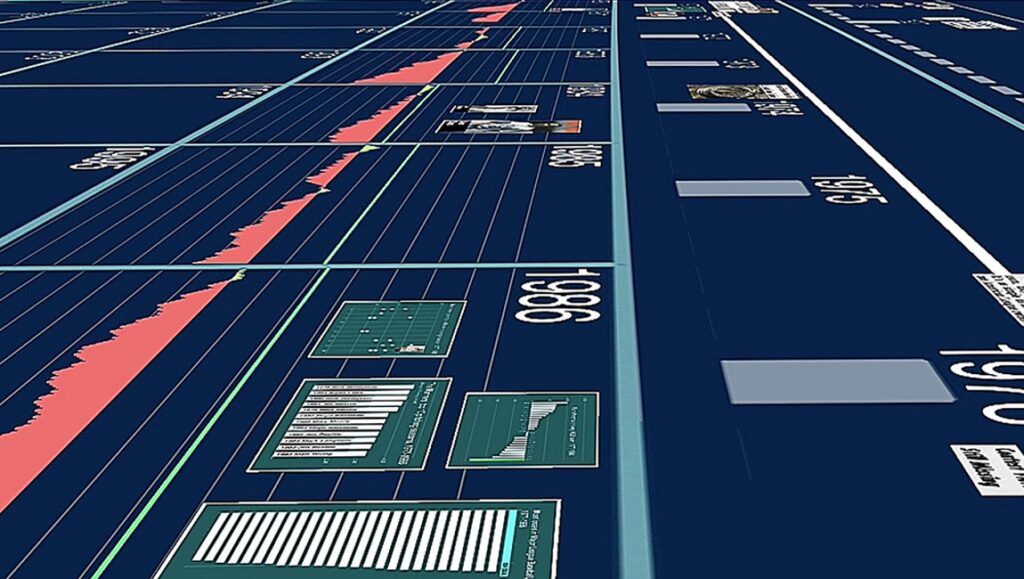

Credit: Sbnation

15. The History of the Seattle Mariners

“The Seattle Mariners are eminently lovable, profoundly human, and stunningly, outrageously weird.” These words come courtesy of Jon Bois, writer, editor, animator, producer, and director of the idiosyncratic and extraordinarily engaging The History of the Seattle Mariners. He’s describing its subject, but he might as well be describing the project itself, a sprawling, intensely funny, and engrossing sports documentary that also happens to be an internet-spawned evolution of documentary form, not to mention an emotional experience unlike any other on the subject you’re likely to encounter. Initially presented as a miniseries of Bois’ and co-writer Alex Rubenstein’s Youtube series Dorktown, and here cut into a 3-hour-40-minute whole, the film treats audiences not only to a thorough reckoning with a sports team’s frequently heartbreaking record, but also to the ridiculous personalities behind it; peppered throughout are absurd stories, like the time a cow was smuggled into the manager’s office or when a hotel room’s entire contents were clandestinely emptied or the equally moving microtales of Ken Griffey Jr.’s 43-hour solo drive from Seattle to Tampa, just because he was lonely. This monument is assembled almost entirely of statistics, very occasionally supplemented with archival footage of actual sporting events, and featuring zero talking heads. The visual scheme is that of a massive chart, with a virtual camera careening through its many subsets as if they were structures set in their own landscape, and the endless synth music seems to echo off the windows of these skyscrapers of data. You’ve never seen sports the way Bois sees sports, but we should all learn to. Matt Lynch

Credit: Amazon Prime Video

14. The Vast of Night

The Vast of Night [is] genre fare, a context signaled immediately – debut director Andrew Patterson situates his film as a Twilight Zone riff, only here titled Paradox Theater, and The Vast of Night is presented as an ostensible episode. Opening to the image of an old-timey cathode-ray tube television, all rounded edges and wood panel trim, the camera then proceeds to zoom and colorize and unfuzz, passing into the TV, so to speak, and commencing the film in earnest. […] The Vast of Night’s influences and touchstones — H.G. Wells, Rod Serling, Roswell lore, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Red Scare propaganda – are varyingly inter-, extra-, and subtextual, both interacting with existing material and subverting familiar expectations. But this is micro-budget cinema, something reminiscent of a lo-fi Stranger Things by way of Primer, and Patterson’s greatest trick, in defiance of budgetary limitations, is to perfect the movement and manner of his film’s kinetic action: both the blocking and choreography are consistently striking, and exhibit a theatrical understanding of the veritable stage, and the clear standout sequence is built on a prolonged medium-closeup of a switchboard, [main character] Fay’s movements and mindset increasingly frenetic even as she artfully manages the patches and plugs with something like balletic grace. Patterson integrates these spurts of deceptive, practical complexity into patient long takes, a strategy which forces viewers to recondition the modes in which they movie-watch, developing and trusting the character dynamism and intensely purposeful mise-en-scène rather than getting bogged down in any rehash of cockamamie alien chestnuts. A return to the represented era’s understanding of science fiction as a genre built on disquiet, and the intrusion of the unknown, The Vast of Night does not just upend its minimalist genesis, but also subsumes its spirit — and in the service of creating something grand from its well-worn parts. Luke Gorham [Excerpted from full review.]

Credit: Berlinale

13. DAU. Degeneration

To delve into the world of Ilya Khrzhanovsky’s DAU. is to forgo the comfortable spectatorial positions of detachment and objectivity, and submit to its fantastical reconstruction of a totalitarian empire. Already, viewers versed in the megalomaniac dictatorships of auteurs and visionaries might balk; and that’s to say nothing of the numerous allegations of psychological abuse inflicted on the project’s 10,000 participants, which have in their wake blurred the lines between the Stalinist microcosm Khrzhanovsky sought to depict and the Stalinist microcosm he ended up shaping. After three years of filming, and a decade in the editing room, the result — fourteen films and an assortment of miniseries, concerts, and documentaries — has, for better or for worse, proved overwhelming for our present cultural sensibilities. Overwhelming as Salò and In the Realm of the Senses proved for their time, heralding a revolution in the presentation of the artistic and the political as interplaying spheres of influence; but also in its grandiose, Caden Cotard-esque world-building of an eerily historical simulacrum. Ranging from the intimate to the epic, DAU.’s films span the decade from Stalin’s death to the political upheavals under Khrushchev and Brezhnev, centered around a top-secret scientific institute whose members race against the Americans towards technological superiority. Degeneration (co-directed by Ilya Permyakov), the last entry chronologically, belongs to the latter period: a six-hour survey of the institute’s last days, as the rigid order of communism gives way to both ideological disaffection and the imposition of a new nationalism. Lev Landau, the genius physicist that gave DAU. its name, has been incapacitated by age and an unhappy marriage; his associates slog away on unending eugenic experiments, disillusioned with the administration’s panoptic control over their personal lives. The younger intellectuals flirt with dance, drink, drugs: debauchery in the panopticon’s eye. And then a two-fold transformation occurs — the state’s apparatuses are tightened, exerted to greater repressive ends, while the emergence of a nationalist youth (played here by real-life Neo-Nazis) paves the way for the institute’s descent into madness and moral iniquity. As the push towards a utopian social order is engineered, an equal and opposite pull is exerted, the everyday human desires, prejudices, and ethics colliding head-on with monoliths of inhuman rationalism. The banality of evil is all too well realized in Khrzhanovsky’s inescapable moral parable; one will find it impossible to remain detached from its oppressive Leviathan. Morris Yang

Credit: Black Bear

12. Black Bear

In the debate between mimesis and anti-mimesis, Lawrence Michael Levine’s Black Bear proffers a third possibility — that life is art in organic action. It’s perhaps inaccurate, and is certainly reductive, to suggest that these are three answers to the same question, as Levine almost certainly does not intend his film to be a refutation of either familiar maxim. But approaching the film with this general framework in mind does lend aid in penetrating its intricate design. A diptych work (one that tantalizingly ends with the promise of an infinite extension), Black Bear is constructed of two tempestuous halves that inform and enrich each other, shifting motivation and pathology among its three primaries and introducing a crucial meta framework. […] But Black Bear is less of a puzzle than an impressionistic articulation of identity lost; teasing out one-to-one connections here is fruitless in the face of the film’s more broadly suggestive tenor, which admittedly both generates and forfeits power. Where viewers are conditioned to expect a certain mode of reality, one that suggests a more casual, governing narrative, Levine is instead content to offer only two tenuous parts that speak to the same truth — that this perhaps untidy amalgam births a greater honesty. Given all this, both Wildean and Greco conceptions of the life-art relationship find footing, but reducing Levine’s playful two-panel contrast to any film-specific discourse is restricting — this isn’t just another self-involved, self-congratulatory film about the act of making film and/or art. If anything, Levine leans toward anti-mimesis, but Black Bear boasts a tragic inflection that subverts such an easy reading: the film suggests, despite the deliberate manipulations its characters employ, that life is refractory, resistant to our efforts at control, which amount to futile, sometimes beautiful and sometimes cruel, works of art. Luke Gorham [Excerpted from full review.]

Credit: Cinema Guild

11. I Was at Home, But…

If those films inextricably linked to childhood experience — those movies, in Serge Daney’s words, “that watched us grow up and saw us… already entangled in the snare of our history” — are about the trouble with being born, Angela Schanelec’s I Was at Home, But… expresses the particular anguish of being responsible for another’s birth. For Astrid (Maren Eggert), a middle-aged widow and mother of two, the question of parenthood resurfaces painfully when her adolescent son returns home only after a week’s disappearance. For a young couple (Franz Rogowski, Lilith Stangenberg), the question has yet to be answered, though it’s considered in so many sleepless, blue-hour reveries. No staid existential rumination, however, Schanelec’s eighth feature is, per the David Bowie cover that features in one key scene, an invitation to dance — not to forget that governing question, but to sublimate it into movement, as if to make one’s body feel what one would ask of it. Incorporating fable-like bookends and daring elliptical leaps, scenes of schoolchildren rehearsing Hamlet and an acute attention to matters of hearth and home, the film’s elaborate choreography might be traced to the works of Robert Bresson, Maurice Pialat, and Yasujirō Ozu. But far from being beholden to these stylistic forebears, I Was at Home, But… is more like a radical rereading of them. If we think of our encounters with these directors as akin to a child’s learning of a first language, then Schanelec’s distinctive découpage reads as poetry — an adult’s reception of that same language, a second inheritance, calling for relearning and rebirth. The film’s radiant penultimate scene, which charts passage to a green island entirely removed from the confines of contemporary urban life, presents us with a mother’s slumber and her children’s tentative steps into the world. Here, rest does not come amid a childlike assurance of being looked after, but when, perchance to dream, we imagine ourselves unguarded, unwatched; when we accept not just that the world can move on without us, but that it must. Maybe then, we can truly call it home. Lawrence Garcia