PVT CHAT hints at sapient commentary of our transactional internet age, but the gesture ultimately proves empty.

Writer-director Ben Hozie’s latest, PVT CHAT, is another film firmly planted within the emerging subgenre of telecom cinema. Given the evolving cultural discourse around the nature of communication and connection in an age of virtual platforms, there is admittedly a rich trove of material here. While Catfish introduced the genre’s (melo)dramatic potential to the mainstream, subsequent entries have skewed toward fiction, frequently embracing horror as their preferred texture; films like Unfriended, Cam, and the recent Host all rely on an undercurrent of technophobia, capitalizing on the viewer’s lack of knowledge of or intimate exposure to certain computer-centric innovations to recontextualize fear of the unknown. PVT CHAT at first, and for a while, suggests that it might morph into this type of horror — while not embracing the Screenlife mode of filmmaking, it nonetheless uses low-angle shots and canted compositions to build a sense of disorientation into its otherwise low-key proceedings. Cramped, dark quarters dominate early on: we see medium shots of an isolated Jack (Peter Veck) hunched in front of a laptop in varying states of undress, while the computer’s screen frames and diminishes all of his social interactions.

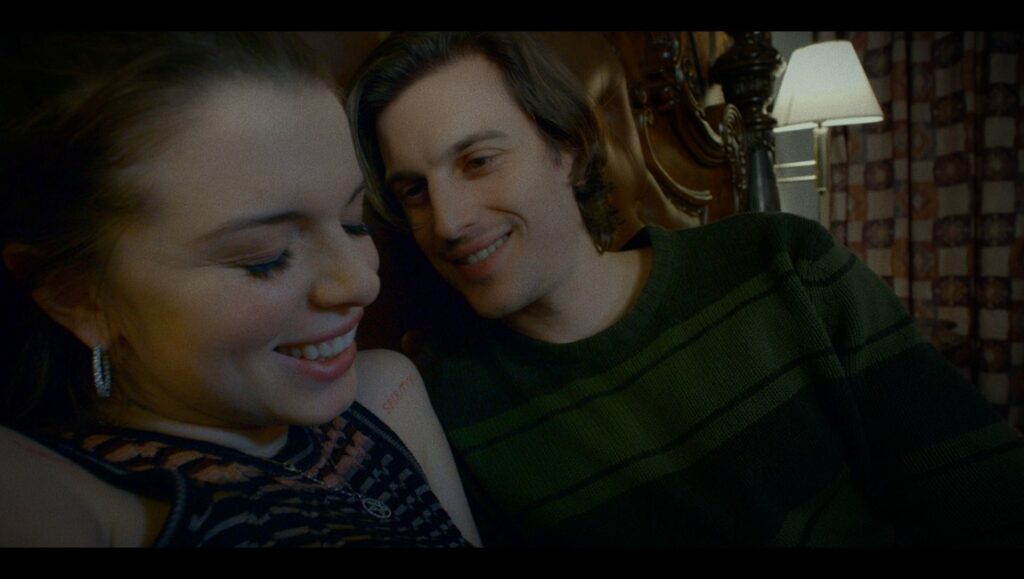

But PVT CHAT soon opens up, mostly to its detriment. Hozie’s film is specifically concerned with camming culture, and it’s more of a relationship film than a stylistic exercise in dread, with Jack as the sad-sack nucleus. He’s a would-be hustler prone to compulsive lying, whether about his fictional tech ventures or his online blackjack prowess, and trawling camgirl chatrooms looking for love. He’s a grating presence, but Veck mostly pulls the performance off, cutting Jack’s more unsettling incel tendencies with a palate-cleansing goofiness. The film elsewhere pads its hip factor with a bit of Safdie cred: the brothers’ regular Buddy Duress once again maximizes his screentime through a performative inclination toward mania, while Julia Fox, as the female lead, proves to be as compelling a presence as her role in Uncut Gems suggested. But despite these isolated strengths and the director’s evident ambition, PVT CHAT isn’t up to either the Safdies’ standards or those of its more horror-minded subgenre fellows. Where the latter films intuit new, if obvious, modes of filmmaking from the material, Hozie seems interested only in its dramatic potential, and even that remains mostly undeveloped. It’s the kind of film that strives to be observational only, mistakenly trusting that its content is sapient enough that poignancy will simply follow rather than actively working to establish any guiding ideas. Its contemporaneous signifiers — anti-capitalist rhetoric, outré installation art, yoga — are broad and insubstantial, scuttling any meaningful interrogation of internet-era transaction and interaction. Hozie mistakes lampoonery for incisive critique, which muddies PVT CHAT’s tone and confuses its attempt at trenchancy. What’s left is a film that unflatteringly plays like a post-mumblecore version of Men, Women, & Children.

Originally published as part of Fantasia Fest 2020 — Dispatch 5.

Comments are closed.