Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched

In 2012, writer and film programmer Kier-La Janisse published House of Psychotic Women, a tremendous and essential text, part autobiography, part confessional, part film-guide roadmap to decades of cinematic depictions of female trauma, desire, and death. It’s one of the great movie books of all time, and Janisse, already well-established in the horror community, deservedly saw her profile rise. Her latest project, the epic documentary Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched, is subtitled A History of Folk Horror, and like Psychotic Women, it’s at once both broad and hyper-specific, comprehensive yet deliberately not a complete catalog. It’s also utterly engrossing and unsurprisingly open-minded about its thesis, which is that “folk horror” is less a genre than a mode, a set of themes and ideas that can be endlessly reconfigured but nevertheless speak to each other.

Running a whopping 3 hours and 15 minutes, Woodlands is never at any point even a little bit boring as it delves into not just traditional ideas of folk horror — say, the distinctly British paganism of a film like The Wicker Man, to use a key text and repeated example here — but works of science fiction and fantasy, other genres like westerns, works from all over the world, and even documentaries. Frequently, digest-docs like this amount to clip reels of strange but famous genre examples, punctuated by enthusiastic plot summaries or production anecdotes from famous talking heads, winding up mostly remedial. Janisse’s film follows no specific chronology, and the movies it references flow intuitively into each other, punctuated by actual analysis from writers, filmmakers, and artists in multiple disciplines, and the clips she chooses from literally dozens of different films wind up creating a dizzying collage of images that constantly communicate with each other. It’s truly a delightful, landmark film and a worthy follow-up, destined to become an important work of criticism.

Writer: Matt Lynch

The Feast

Lee Haven Jones’ The Feast is rather a perfect companion to fellow SXSW title Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched, touching on all of the folk horror pet themes the documentary associates with the subgenre. Filmed entirely in Welsh, it’s a simple — even quaint — exercise. Glenda (Nia Roberts) and her husband Gwyn (Julian Lewis Jones), an apparently wealthy couple, are preparing to host a dinner party. They’ve hired a hostess for the evening, a young woman named Cadi (Annes Elwy), and right away the ever-so-slightly-spooky stuff starts happening. Cadi never speaks and seems timid, almost childlike even. Dirt stains seem to appear wherever she’s been, although she’s perfectly clean. And she somehow knows by heart an old song Glenda used to sing with her mother. Meanwhile, the couple’s troublesome sons, Guto and Gweirydd (Steffan Cennydd and Sion Alun Davies, respectively) appear aggressive and dangerous, with the former having what seems at first to be a minor accident with an ax and the latter pursuing his special diet of raw meat.

Most of The Feast is taken up by the family’s bickering, the increasingly ooky issue with Guto’s injured foot, and the banqueters being alternately amused and repelled by Cadi’s precocity. Glenda seems particularly unpleasant, insisting to one of the guests, their banker, that they’re about to strike it rich by selling drilling rights to their acres of land, which has been in the family for generations. Strangely, when people start coughing up hairballs or nearly having heart attacks or what have you, Cadi springs into action to assist, and nobody seems particularly perturbed afterward. Is she a stranger trapped with a bunch of rich assholes, or is she perhaps the source of these disturbances? Three guesses.

There may be some cultural specificity to Wales that’s being missed by this assessment, but even if so, down to its bones this is a story of people spiritually and physically detached from their land, metaphorically disentangled from their roots, and Cadi is, of course, the vengeful spirit that’s come to disrupt their lives, making this almost a dirt-caked variation on something like Teorema, but without the directly political subtext. It’s a fine feature debut for Jones, and he shows skill in complementing his eerie tone with compositions largely consisting of lovely but placid master shots and gnarly inserts, ultimately making the most of his two main locations: the angular, minimalist house and the foggy, damp surrounding of forest and cliffs.

Writer: Matt Lynch

Here Before

Stacey Gregg’s Here Before has all the markers of a good movie. Despite its short runtime, it proceeds at a measured pace that gives the appearance of grace. It is elegantly and thoughtfully composed, using doorways and natural obstacles to frame its characters, often isolating them to better evoke a sense of interiority. And it sports another good, nervy performance from Andrea Riseborough, a reliable purveyor of good, nervy performances. Beyond this, it also appears at first to be a quiet, empathetic film about a woman’s grief and fragile mind. But Here Before is also a fatally stupid movie, as interested in pitched, contrived melodrama and moronic twists as it is in aspiring to poetry.

The film concerns Riseborough’s Laura, a mother still shaken by the recent death of her daughter, Josie. When a new family moves into the other half of her family’s duplex, she takes a maternal interest in their daughter, Megan. On several occasions, Megan insists that she’s been “here before,” whether she is referring to places like the park Laura took Josie to or the cemetery the other girl is buried in. It’s only a matter of time before Megan is more openly suggesting that she is Josie, pushing Laura to an emotional breaking point. This results in what is largely an enervating domestic drama, like a series of confrontations between Laura and Megan’s mother, and a few nightmares for Laura. These nightmares are the most compelling part of the movie, suggesting the supernatural evil child picture it should have been. But there’s nothing supernatural about Here Before and its twist ending doesn’t allow even a sliver of tantalizing ambiguity. I won’t spoil the twist, but in the interest of grounding the film in definite reality, Gregg offers an explanation for Megan’s behavior that is so contrived and preposterous it almost loops around to being funny.

That’s too bad, too, because the movie does at times suggest a compelling, empathetic portrait of a woman dealing with something possibly extraordinary. The explanation isn’t quite ordinary — it is ridiculous — but it plays like nothing more than a mean trick, instantly flattening the thoughtful and troubling possibilities of supernatural reading into the stuff of a rote psychological thriller. In this light, the apparent compassion that otherwise pervades the film, which might be mistaken for genuine empathy, starts to feel like table-setting for watching a woman lose her mind as she is gaslit by a 10-year-old.

Writer: Chris Mello

Our Father

At first glance, the plotting of Bradley Grant Smith’s directorial debut feature Our Father would seem to offer plenty of promise. Beta (Baize Buzan) and Zelda (Allison Torem) are distant sisters from entirely different worlds — one an uptight, white-collar girl and the other a gloomy, carefree Bohemian “psycho” — who, after their father’s suicide, embark on a journey to find their strange, “religious nut” uncle who has been vanished for thirty years. It’s a narrative setup that immediately intrigues, not least of all because it’s tough to recall that last film that featured two young sisters sharing a quest to find a lost male family member. Unfortunately, this dramedic odyssey runs out of fuel far too soon, petering out all while still going in circles. Much of this can be blamed on the lowkey mumblecore leanings that Smith opts for, everything tending heavily toward the brand of naturalism that is all too familiar in works of this ilk, and which too easily slips into flavorless tedium. Likewise aesthetically underwhelming, almost everything here is shot in dim lighting, presumably an attempt to create a minimalist, relaxed vibe, while the film’s narrative also fails to build any layers into its single-thread story or develop protagonists’ who meaningfully develop or even come into much conflict. And while the acting duo of Buzan and Torem does achieve a welcome chemistry, specifically during the film’s more intimate sequences, they don’t fare as well during scenes of sisterly confrontation — and that’s even disregarding just how uninteresting these two characters are. Elsewhere, it’s unclear why Smith insists on frequently digressing into unnecessary and imposed subplots only for the sake of a shallow critique of sexism, all of which is facilitated by some very cartoonish male morons.

More beneficial to the film is the fact that Smith is also a musician, and he executes a steady rhythm, carefully handling material that is often disjointed, inconsistent, and unconvincing. Perhaps predictably, he also frequently demonstrates a facility for integrating music into the film’s intervals, effectively punctuating moments and, in that way, managing to at least engage viewers through it all. Ultimately, as the film concludes, a couple twists actually help the narrative from nose-diving into outright predictability — although, it’s not entirely clear why Smith suddenly decides to render a scene with Beta and her uncle Jerry (Austin Pendleton) at a piano in abstract blue lighting, even if the theological and metaphysical aspect of the scene is obvious, and it again exhibits how impulsive and uneven his directorial instincts can be. But eschewing patness one final time, just as it seems that all of this will have amounted to nothing more than a futile journey where the girls will ultimately embrace their everlasting sisterly love for one another; Our Father settles things on something of a bleaker note, revealing that Beta may not find exactly what she’s been looking for — or at least, not entirely in the way she hoped. In other words, the lesson learned is that it’s crucial for one to persevere in life, despite any turn of events. In this sense, Smith should take note, as there’s enough here to suggest that he may well have a long, successful career in front of him. But this time out, it has to be said, he sets the bar too low and doesn’t do enough to upend the film’s considerable convention.

Writer: Ayeen Forootan

Paul Dood’s Deadly Lunch Break

The most interesting aspect of the new comedy Paul Dood’s Deadly Lunch Break is its unwieldy title, an attention-grabber that promises a rollicking good time but instead only serves to set the viewer up for disappointment. This low-energy Edgar Wright knock-off assembles an ace squad of British film and TV stars — including Tom Meeten, Katherine Parkinson, Kris Marshall, and Alice Lowe, among others — and gives them next to nothing to do, presenting a “satire” that feels about 20 years too late to the party. Paul Dood (Meeten) is a middle-aged sad-sack still living with his elderly mother and working a menial job at a resale shop in the local mall. Paul desperately wants to be a flashy rock star in the vein of David Bowie — all handmade, sequined jumpsuits and flowy scarves — and sees his opportunity when a hit reality television show in the vein of America’s Got Talent holds auditions near his sleepy English village. Unfortunately, five individuals end up preventing Paul from achieving his dreams, and so he goes on that titular lunch break, exacting revenge on those who have turned his life into a living hell.

Unfortunately, director/co-writer Nick Gillespie muddles his intentions regarding our protagonist: is Paul some pathetic loser meant to be mocked and ridiculed, or is he a committed, driven man whose misfortunes deserve our sympathy? The answer, it turns out, is basically, “whatever is convenient to the plot,” resulting in an inconsistent and bumpy ride. It doesn’t help that the five people he sets out to kill are rendered as cartoonish villains, their selfish acts presented in the most banal ways possible. It’s the same joke, ad nauseam: an unfounded sense of superiority plagues each individual Paul encounters, ultimately preventing him from reaching his destination in time, whether it be a railway worker who doesn’t know how to assemble a ramp or a devious priest and his assistant who steal a taxi in the name of God. And it’s not even worth getting into the Englishman who fancies himself a Japanese samurai —there is far too much to unpack (or, maybe not) there. Even the revenge scenarios are plagued by repetition, as each person inadvertently causes their own demise, leaving Paul blameless. Meanwhile, Paul is chronicling his events over the Internet, leading him to become a worldwide sensation. Not that this film actually has anything to say about the connection between fame and infamy, though, as that would imply it was even remotely successful as a satire instead of merely latching on to anything that seems topical. The sheer laziness on display reaches its zenith at film’s end, with text telling us what happens to these characters after the events of the film, a conceit that stopped being funny around the time of Animal House and ludicrously suggests that any viewer would ever give another thought to these characters once the credits roll. It proves especially surprising that Gillespie — who has served as second unit director on numerous Ben Wheatley films and as DP for Shade Meadows — would produce digital imagery this dull and lifeless. Perhaps he was as uninspired by the material as every viewer forced to sit through it. Shout-out to Meeten, though, who gives a truly game performance — he’s the only one who makes it out of this lunch break unscathed.

Writer: Steven Warner

Offseason

Thirty minutes into Offseason, Marie Aldrich (Jocelin Donahue) tells her beau, George (Joe Swanberg), that the island she has dragged him to may be the home to a very spooky curse, the result of a deal some settlers made with a sea monster long ago — or so said her late mother. Sensibly not believing that story, she has only come to this island because her mother’s grave has been vandalized and it’s urgent that she set things right. When she becomes trapped on the island — the drawbridge goes up at the start of the offseason and won’t go down until spring — Marie discovers that the curse is real and all the townsfolk become possessed, hauntingly still zombies throughout the offseason.

This is well-trodden ground, but as with most generic set-ups in the genre, it can be fertile territory for a novel idea or a filmmaker with a good sense for horror. Director Mickey Keating, unfortunately, has neither the good idea nor the chops to turn this into an effective scary movie. Instead, he seems most interested in aesthetics, both his own and that of his obvious cosmic horror influences. The result is the most shallow of Lovecraft homages, complete with an eldritch abomination from the sea but missing any actual interest in the Weird or unknowable. It plays like the work of someone whose only experience with Lovecraft is from barely paying attention while watching In the Mouth of Madness. Maybe that’s for the best, as this very white film does not possess any of the writer’s racism, but careless deployment of overused tropes turns Offseason into little more than a thoughtless genre exercise that plays with signifiers but means nothing.

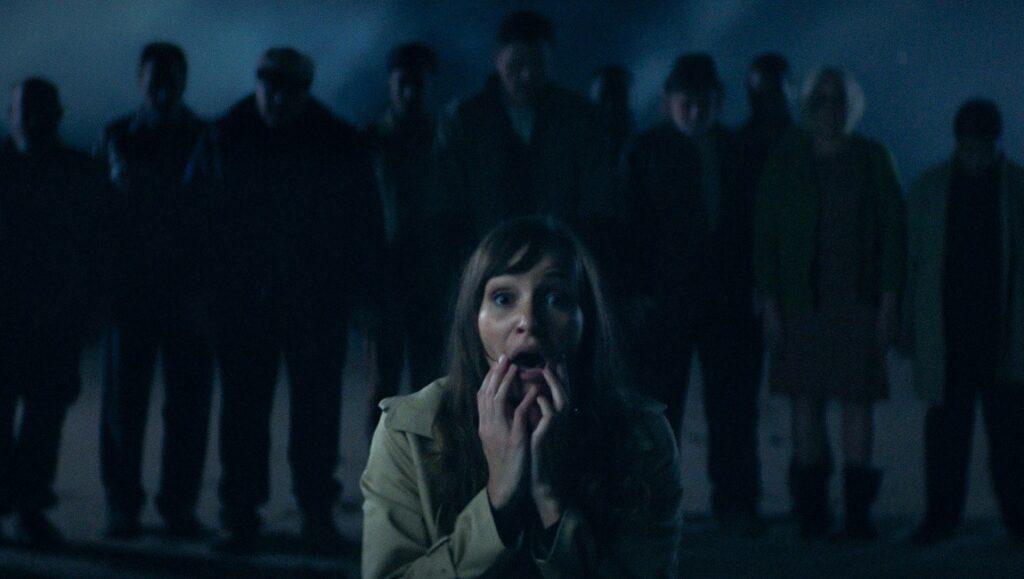

As a meaningless genre exercise, it fares a little better, as Keating is not an incompetent filmmaker. This is a slick film, defined by studied steadiness in the camerawork and an evocative color palette dominated by blue and red lighting. When Marie gets lost on the island and wanders through the empty township, the glide of the camera and measured editing make for creepy stretches of tension building. The issue is that, when things come to a head and Keating has to break tension with a scare, he gives in to some bad aesthetic impulses. Take for example a scene at the diner where Marie stumbles upon the townsfolk posed like mannequins, their eyes rolled back into their skulls. Suddenly, a horde of people appear behind her — an image repeated throughout — and one of the women grabs her. Keating films this in baffling slow motion, deflating all tension rather than releasing it. It’s a choice that is symptomatic of the structure of all the ostensibly scary moments in the film. If the effect is supposed to be artful and lend weight to these sequences, Offseason’s framework is far too shabby to support it.

Writer: Chris Mello

Comments are closed.