OK, so things don’t really vanish anymore: even the most limited film release will (most likely, eventually) find its way onto some streaming service or into some DVD bargain bin assuming that those still exist by the time this sentence finishes. In other words, while the title of In Review Online’s monthly feature devoted to current domestic and international arthouse releases in theaters will hopefully bring attention to a deeply underrated (even by us) Kiyoshi Kurosawa film, it isn’t a perfect title. Nevertheless, it’s always a good idea to catch-up with films before some… other things happen.

A Dim Valley

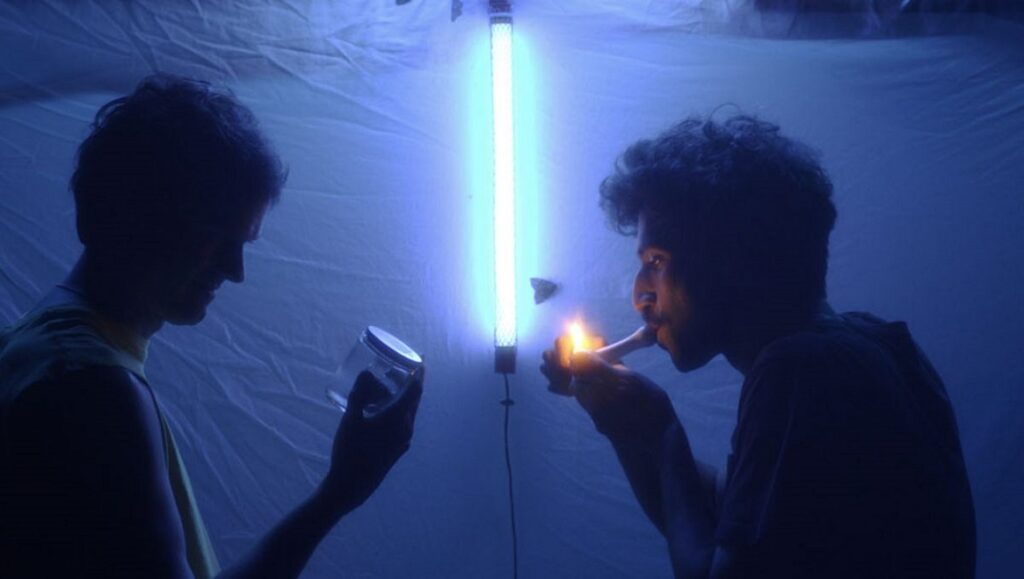

Shot through a gauzy haze, at once evoking a sense of nostalgia while also displacing the film from any specific time period, Brandon Colvin’s A Dim Valley is a fairly unique comedy made out of borrowed pieces of cultural memory and signifiers. One must qualify with “fairly unique,” as A Dim Valley is certainly of a particular American indie aesthetic that’s been especially popular this last decade — most recently Ham on Rye and Two Plains & a Fancy; most iconically, For the Plasma — placing the film within a specific lineage, though Colvin’s screenplay has a humor and philosophy all its own, confidently carrying the film up and over the pitfalls of cliche and redundancy.

Set at a scenic eastern Kentucky campground, removed from civilization, A Dim Valley initially concerns itself with three men — 2 grad students and their professor — who have set up camp there to conduct a summer research project. Despite the high-minded pretext for gathering these three together in the remote wilderness, no one seems terribly focused on science, with Whitmer Thomas and Zach Weintraub’s spaced-out grad guys mostly getting stoned and fucking off, their grumbly mentor (Robert Longstreet) bumbling around, failing to keep them in line. Their dynamic is cleverly appropriated from the likes of ‘70s/’80s Summer Camp cinema, borrowing iconography and language from such films, getting big laughs out of filtering them through the stilted, arch style of delivery and performance embraced by the cast (and indeed, every actor is quite committed and quite funny).

Colvin’s riff on this archetypal plot continues when the boys’ isolated summer hang is upended by the arrival of a trio of female backpackers (one of whom is played by For the Plasma’s Rosalie Lowe) whose semi-mythic qualities force these two to reckon with the homoerotic tension underpinning their languid days together. A Dim Valley’s great appeal is that it handles the big emotional journey at its center with a sense of wit and whimsy that keeps the screenplay away from easy beats and payoffs without selling out its characters or playing their relationships as frivolous. The film is distributed by Altered Innocence, a company whose catalog represents something like a canon of actually interesting contemporary queer cinema, and A Dim Valley nicely aligns with the brand’s taste for the forward-thinking, a familiar tale of queer yearning and exploration, rendered bright, funny, and new by a filmmaker with a developed sense of style.

Writer: M.G. Mailloux

Can You Bring It: Bill T. Jones and D-Man in the Waters

Following the evolution of the titular groundbreaking dance piece, D-Man in the Waters, in the three decades since its release, Can You Bring It weaves together three iterations of the performance alongside interviews with key figures in its construction. Beginning even before its inception, with the artistic and romantic partnership of Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane, the documentary chronicles the tragic impact of the AIDS epidemic on the pair and their dance troupe, as well as the death-defying legacy of the work that emerged from that traumatic period.

From its earliest moments, Tom Hurwitz and Rosalynde LeBlanc’s film asks viewers to leave any preconceived notions they might have about dance at the door. “This is not a balletic piece,” explains Associate Professor Rosalynde LeBlanc Loo: “It’s lyrical, but it’s athletic.” The film more or less follows the same principle, less concerned with the ornamental side of the dance, and instead delving into the mechanics of how exactly the piece came to be, on both a macro, cultural scale and the micro scale, deconstructing individual moves and sequences. The piece is inseparable from the context it was created in, but rather than offering up some stuffy history lesson, Can You Bring It emphasises the direct impact of this history on the creative process. In a particularly elegant move, the filmmakers show how that creative process is adapted by contemporary artists, with the work shaping a new generation of dancers just as much as they shape it.

It’s in one of these detailed deconstructions of the piece that the film’s true emotional significance emerges. A man holds a woman’s hand, guiding her as she runs up another’s spine. She leaps, suspended in the air for one harrowing moment, before being caught safely. To audiences, especially those uninitiated in dance, it’s a stupefying move — it may only last an instant, over before it’s even really begun, but for a beautiful, terrifying second, the dancer entrusts her body entirely to another. In retrospect, the original dancer admits, the move, though nerve-wracking, was never that dangerous. Her leap was understandably cautious, only really leaving the other dancer’s back for a second before being caught. However, in the countless productions since, dancers have taken more risks, each incarnation pushing the piece, and their bodies, to the limit, leaping further each time, until the move becomes a deliberate, breathtaking dive. With every new iteration, D-Man is a piece that becomes increasingly ambitious, building on earlier iterations and, as Can You Bring It so perfectly captures, this is an act of empowerment. For every dancer who leaps, trusting in others to catch them, there is a new generation spawned, trusting in their instincts and their communities, willing to leap higher and further than ever before. The process is a mutual one, and by probing into the minutiae of this process, the film becomes an ode to the creative process and the exact ways art can impact, and be impacted by, the world around it.

Writer: Molly Adams

Broken Diamonds

The portrayal of schizophrenia in film is often problematic, to say the least, as the afflicted are often presented as either violent-prone and sadistic or kooky and misunderstood. When one of the more positive examples in the schizophrenia canon is Ron Howard’s A Beautiful Mind, a film which loosely treats disorder as a potential superpower and essentially implies that you can will away mental illness, then you know the competition is dire. Perhaps that low bar is why it’s rather difficult to be too hard on Broken Diamonds, director Peter Sattler’s well-intentioned film about the devastating effects schizophrenia can have on the family members who end up in its orbit. Writer Steve Waverly based the screenplay on his own experiences growing up with a schizophrenic sister and the extreme toll it took on his family, so there are plenty of personal stakes imparted. Unfortunately, the movie falls into the same trap as so many of its brethren: using the illness to encourage some cheap laughs and easy tears.

Ben Platt stars as Scotty, a twenty-something writer heading to Paris in a couple weeks in order to become the next Hemingway or some such nonsense. But the unexpected death of his father sends his life into chaos, as Scotty is soon forced to temporarily care for his schizophrenic sister Cindy (Lola Kirke) while they await her placement in a new mental health facility. Things quickly spiral out of control when Cindy stops taking her meds, resulting in her eventual disappearance. The biggest problem with Broken Diamonds, then, is that it’s unable to determine where within its story to actually fix its focus. The film is ostensibly about Scotty and the long-standing struggles he has endured as a result of his sister’s mental illness, with numerous flashbacks showing how it affected both his childhood and his parent’s already fractious marriage, but aside from a few cursory discussions, it’s an aspect left mostly unexplored, the remainder of the film’s running time instead mostly made up of Cindy’s exploits. Oh, and montages set to obscure indie rock cuts — so many montages.

Cindy, unfortunately, comes from the Benny and Joon school of schizophrenia, her alarming actions mined for comedy for most of the film’s slim minutes, until suddenly they’re not. It amounts to a fair amount of tonal whiplash, which, while perhaps reflective enough the way schizophrenia often manifests, doesn’t work narratively here in the absence of any intentionality or thematic shepherding. Kirke has proven to be a genuinely fantastic actress and understated presence in movies like Mistress America and Gemini, but her performance here, while never coming across as mean-spirited, is still overly theatrical in a way that feels like actorly posturing. Platt, for his part, spends most of the film either holding back tears that hang precariously on his bottom eyelids or letting the levees break and vigorously wiping his face with the back of his hand. It’s only upon the film’s closing credits that we experience anything resembling authenticity, as real-life schizophrenia sufferers and their family members are invited to share their stories via a filmed group therapy session involving Platt and co-star Yvette Nicole Brown. It’s obvious that the subject matter means so much to everyone involved in the production, but, as is always the case, good intentions can only get you so far. Those who suffer from schizophrenia — including loved ones who sacrifice so much — deserve better than the affected and messy Broken Diamonds, but the fact that the film isn’t outright offensive like so many others of this ilk is at least a step in the right direction, no matter how small.

Writer: Steven Warner

Rock, Paper and Scissors

There’s something very wrong with Maria Jose (Valeria Giorcelli) and her younger brother Jesus (Pablo Sigal). Living a hermetic existence in the dilapidated home of their recently deceased father, the pair lounge around watching The Wizard of Oz on a loop, ignoring phone calls and playing games of rock, paper, scissors to decide who has to answer the door. Interrupting this odd, off-putting reverie is their older half-sister Magdalena (Agustina Cerviño), who’s arrived from Spain to help them get their father’s affairs in order and claim her portion of the inheritance. The trio of siblings haven’t been together in years, for reasons that become clearer as the film progresses, and their conversations are awkward and stilted. It’s obvious that Magdalena doesn’t really want to be there, and Maria Jose acts as if she hasn’t communicated with another human being for quite some time. There’s a pronounced undercurrent of passive aggressive animosity, as Maria Jose and Jesus detail caring for their father following a failed suicide attempt that left him an invalid, and Magdalena apologizes for never coming to visit or assisting in the caretaking. After spending an uncomfortable night in the house, Magdalena attempts to take her leave from her siblings the next morning. Shockingly, Magdalena suddenly falls down the home’s grand staircase and awakes in a horrible predicament — hooked up to the same medical equipment used to care for their father, unable to move due to her injuries, with no cell phone and no means of communication with the outside world. She’s now Maria Jose’s patient, but once she accuses Maria Jose of purposefully pushing her down the stairs, it becomes obvious that she’s really a prisoner.

Co-directors Martin Blousson and Macarena Garcia Lenzi create a palpable sense of unease from this bizarre scenario; Maria Jose seems to relish playing nurse just a little too much, while Jesus tries to reassure Magdalena that she’ll be free to leave as soon as her wounds heal. But, as Maria Jose becomes increasingly unhinged, Magdalena begins trying to ingratiate herself to Jesus in an effort to turn the two against each other. The problem is, Jesus turns out to be just as unstable as Maria Jose, and it becomes less clear who is manipulating who. Like the titular game, the narrative begins bouncing back and forth, with Magdalena constantly trying to suss out which of the two might be the most sympathetic to her plight at any given moment. This all works, for a while, but gradually Rock, Paper and Scissors, like its namesake, starts spinning its wheels, repeatedly treading the same ground to diminishing effect. The filmmakers never really ratchet up the tension, either, instead settling on the merely odd and leaning into camp, a la Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? Jesus fancies himself a filmmaker, and the brief glimpses of his chintzy, low-fi home movie play like an 8-bit digital reimagining of Alice in Wonderland. Meanwhile, Blousson and Lenzi really lay on the Wizard of Oz iconography with a trowel, constantly inserting closeups of shoes and characters muttering variations of “There’s no place like home.” Even with a brief 80-minute runtime, the film starts to feel padded; nothing here approaches actual psychological realism, nor does it ever quite go the full Grand Guignol either. This is all mood and atmosphere dissipating into a shrug of a denouement, shying away from extreme violence and only hinting at the psycho-sexual possibilities inherent in such a hot-house environment. Sometimes genre films are accused of going too far; Rock, Paper and Scissors doesn’t go far enough.

Writer: Daniel Gorman

The Man with the Answers

A well-meaning and tentative entrant into the realm of slow-burn road trip romances, Stelios Kammitsis‘ The Man with the Answers is perhaps most noteworthy for telling the story of an all-male relationship in which its characters never once have a discussion about sexuality. This understated tale of greek diving champion Victor (Vasilis Magouliotis) and German traveler Matthias (Anton Weil), who meet on a ferry and end up journeying together from Italy through Germany, exhibits a curiously dispassionate approach to detailing intimate connection, which frustratingly prevents its central bond from ever feeling truly vital. The script’s humdrum attitude toward interaction hardly helps matters, with prosaic dialogue that offers few opportunities to identify with either man (this is particularly true of Matthias, who, in spite of Weil’s charismatic performance, remains a bit of an enigma throughout), resulting in many inert scenes that discourage viewers from ever becoming fully immersed in their encounter.

There seems to be a real reluctance on Kammitsis’ part to offer an upfront discussion about queer identity, ably demonstrating that a film about romance can remain undefined by sexual orientation, but at the expense of threatening to alienate some of his audience. The representation of gayness in cinema has certainly come a long way since homosexual male characters were predominantly AIDS victims or the token best friend, and still, there’s something dishonest about a depiction of same-sex lovers in which they feel detached from their own sexuality. One would expect a natural point in a conversation for the subject of sex to arise between Victor and Matthias, and yet it never happens, as Kammitsis is evidently unwilling to have them relate to each other through their own experiences. And ultimately, that’s what is most conspicuously absent from The Man with the Answers, which, in an increasingly dating-app-dominated world, crucially fails to articulate the raw excitement that comes from meeting somebody in a truly organic setting.

Writer: Calum Reed

Long Story Short

From the guy that played Kano in this year’s Mortal Kombat reboot comes Long Story Short, an Australian romantic comedy that basically takes the third act of Adam Sandler’s Click and stretches it to feature length, with the final product about as successful as all of that would imply. Rafe Spall stars as Teddy, the type of guy who never seizes the day and puts everything off until some undetermined “later.” In a meet-cute so nauseating that barf bags should be handed out to viewers along with their ticket purchase, Teddy accidentally kisses Leane (Zahra Newman) at a New Year’s Eve party, mistaking her for his girlfriend because they are both wearing the same dress, and making Teddy the dumbest man on the planet. Thing is, Leane was unfortunately eating pralines at the time, and Teddy is deathly allergic to nuts, and so viewers are quickly afforded some EpiPen shenanigans to accompany this meeting. To recap, this is all within the first two minutes of the film. Jump ahead four years, and Teddy and Leane are finally to be married, but not before running into a mysterious older woman (Noni Hazlehurst) who gifts Teddy a seemingly innocuous tin can. But as Teddy soon discovers, this tin can magically transport him one year into the future each time he wakes up, specifically to the day of his anniversary. He has no knowledge of what has transpired in the past 364 days, leading him to the shocking revelation that he must appreciate his loved ones and live each day to the fullest, because time is short.

At only 94 minutes, Long Story Short still feels like an eternity, thanks to a structure that is the very definition of repetition. In the early going, Teddy is unable to understand what exactly is happening, so most of the story involves him desperately trying to find his bearings, a detail that is certainly understandable and pragmatic but also enervating to endure. Each new day — or more precisely, year — finds Teddy simply trying to play catch-up, attempting to piece together just how he so badly fucked up his life. The metaphor is obvious, something that even a film as broad as Click figured out and understood to limit to 20 minutes. The majority of Long Story Short consists of Spall standing around making wry observations to himself, some of which are amusing, but most of which are obnoxious. Spall and Newman are at least quite likeable actors, offering periodic respite from the narrative’s drudgery, with Newman especially bringing a surprising amount of emotional heft to a role that is sorely underwritten. Comedian Ronny Chieng also pops up for a few brief scenes as Teddy’s best friend, and he offers further reprieve, ably fulfilling his comedic duties and becoming the best part of the movie (pro tip: more Chieng, less of the rest). Meanwhile, writer-director Josh Lawson does nothing of much interest visually, save for a final five-minute stretch where Lawson gets to flex with a single unbroken shot as Teddy finally realizes the error of his ways; long takes are admittedly old hat and usually misused at this point, but it’s actually a nice touch as realized here. Plus, the New South Wales setting offers plenty of stunning imagery, but so do any number of 30-minute specials on The Travel Channel, and they’re far less demanding affairs. Long story short, if you are in the mood for some romance and a few laughs, you can do better than this repetitive and grueling film.

Writer: Steven Warner

Rebel Hearts

Uplifting and unashamedly radical, Rebel Hearts, the sophomore effort from Pedro Kos, traces the history of the shockingly progressive Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary from their start as a rebellious chapter of the Catholic Church to their modern utopian community. Utilizing a carefully edited combination of interviews, archive footage, and animation, Kos weaves a David-v-Goliath story of defiance, providing an in-depth look at a remarkable group of women.

What’s unfortunate, then, is that the documentary itself isn’t all that remarkable. For all its stylish animation and what may be attempts to emulate Sister Corita Kent’s vibrant artistic style, Rebel Hearts fails to live up to its own impressive subject matter, reducing the Sisters’ complex struggle to just over ninety minutes of feel-good fare. And though easy to understand why Kos leans into a narrative that lionizes the Sisters at the expense of any real complexity, this approach reduces Rebel Hearts to a black-and-white tale that refuses to actually tackle the tangled webs of institutional religion, and instead paints its villains in overly broad brushstrokes. What makes this all the more frustrating is that Kos manages moments of stunning prescience, fueled by his subjects and their clarity of purpose, fishing out fascinating observations about the cycles of abuse in Catholic schools and the interconnectedness of different types of systemic oppression. However, as quickly as they appear, these flashes of contemporary relevance are gone, with Kos returning to a simpler, more easily digestible narrative. For example, in one particularly uncomfortable segment, dissenting nuns who reported back to the cardinal about the activities of the Sisters are carelessly depicted as catty spies, apparently sabotaging their sisters for little more than a condescending pat on the head and a kind word from their patriarchal superiors. Kos does nothing to contradict this narrative, even indulging it with a dramatic animation, a decision that jars against the hippie-tinged progressivism the rest of the film attempts to embrace.

All of this leads Rebel Hearts down an irritatingly non-rebellious route that even its radical subject matter cannot correct. Conventional, wholly palatable, and even a little staid in places, Kos creates a story that, while admirably bringing more attention to these remarkable women, doesn’t live up to their legacy, and is not likely to leave a lasting impression.

Writer: Molly Adams

Comments are closed.