The Summit of the Gods proves that the new subgenre of mountaineering movies can successfully and beautifully extend to the world of animation.

The rapidly growing genre of climbing movies may just see its first major anime entry in The Summit of the Gods, a French-language adaptation of Jiro Taniguchi and Baku Yumemakura’s manga series of the same name. Directed by Patrick Imbert, it interweaves a contemporary storyline with the historic climb of George Mallory, who died in 1924 while attempting to summit Mount Everest. Fast forward to the 1990s, where Makoto Fukamachi (voiced by Damien Boisseau), a photojournalist, searches for a renowned but elusive climber named Habu Joji (Eric Herson-Macarel). In their first encounter, Joji claims to have recovered Mallory’s long-lost Vest Pocket camera. It’s an almost priceless find, and could hold the key to a decades-long mystery: did Mallory actually make it to the top? In pursuit of the camera, Fukamachi tracks down Joji in the foothills of Mt. Everest, where he’s preparing for a dangerous solo winter ascent of the face that claimed a rival’s life years prior.

The first half of the film mostly traces Joji’s career, from his role in a tragedy that kills a younger climbing partner to a harrowing near-death experience alone in the Alps. But unlike many other mountaineering movies, The Summit of the Gods takes a more melancholy approach to the activity. Fukamachi observes Joji’s relentless compulsion to keep climbing with something closer to pity than exhileration; as he notes, there’s always the drive to go even higher, or modify already difficult routes to make them even more punishing. “Basically, it never ends,” Fukamachi says with a tinge of sorrow.

Which brings the two men to Everest, as Joji attempts to summit — without oxygen — while Fukamachi tails him for an assignment. They gruffly agree that, since it’s a solo climb, there will be no intervention should assistance be needed. With this rule in mind, the film’s final third morphs from character study into thriller as the men battle the elements in pursuit of the peak. In one scene, Fukachami passes out from oxygen deprivation while a massive storm barrels through. Hanging to the face of the mountain by two ice axes and a piton, the screen alternates between pools of blood red and flashes of lightning as he loses motor functioning, then consciousness — it’s as much a visual depiction of dwindling oxygen as a metaphor for the all-consuming nature of the two men’s’ pursuits. Joji worked the Everest route for eight years, dropping off the grid entirely to do so. And Fukumachi, undoubtedly the lesser climber, wouldn’t be there at all if he weren’t so driven to solve the mystery of Mallory’s death.

When Fukamachi suggests using the camera to determine whether Mallory summited, Joji dismisses the question out of hand: “what’s the difference?” This unsparing sentiment applies to mountaineering in general: what does it matter who summited what, when, and with or without this or that piece of equipment? Mountains are pristinely indifferent; it’s only humans who ascribe meaning. After the storm, the men part ways: Fukamachi retraces his crampon-steps toward safety while Joji presses on. The relationship between these two quiet, obsessive men reflects the film’s emotional core, so much so that when Fukamachi finally does acquire Mallory’s camera, it feels more like an afterthought than a culmination.

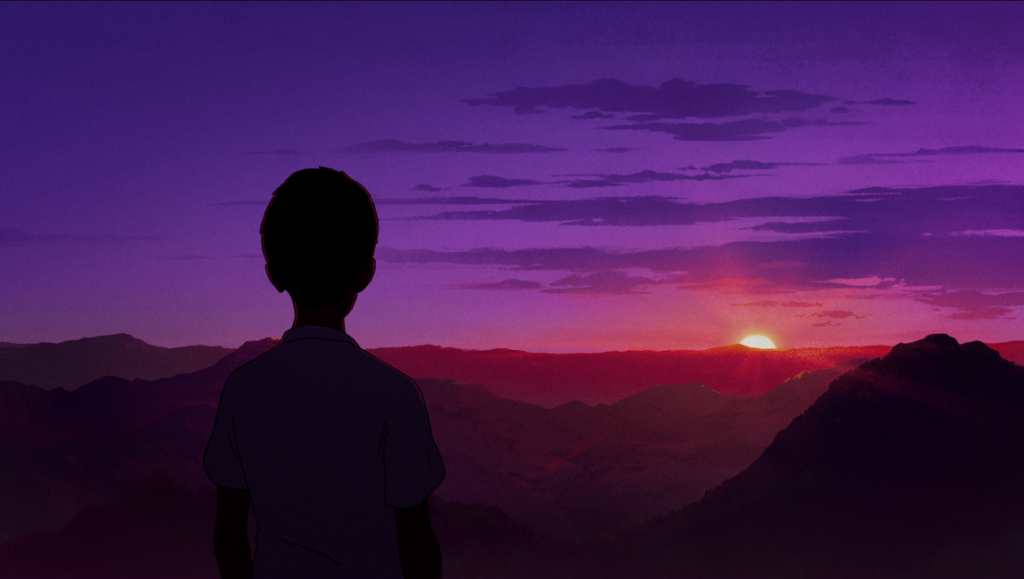

The recent spate of climbing films means that audiences generally know what to expect in the visuals department: sheer faces and jaw-dropping panoramas, often captured via drone, that deliver white knuckles, sweaty palms, and gasps of disbelief. While The Summit of the Gods probably won’t get the benefit of an IMAX release, its medium allows it be what climbing movies generally aren’t: poetic. In one scene, the passing of time is indicated by the gentle build-up of snow on a Nepalese mountain shrine, a conceit that manages to convey grief and hopelessness without the benefit of dialogue. The climbing scenes are often quiet enough to focus on the crunching of crampons and axes, with heavy breathing underscoring the characters’ proximity to danger. There’s a refreshing lack of chatty banter and a small enough cast that the film, for all its majesty, feels startlingly intimate. The Summit of the Gods may ask the big questions, but gives its viewers ample space to ponder the answers for themselves.

You can stream Patrick Imbert’s The Summit of the Gods on Netflix beginning on November 30.

Comments are closed.