ClayDream offers viewers a comprehensive account of a fascinating subsection of cinematic history.

These days, animation is basically synonymous with the glossy phantasms churned out by the likes of Disney and Pixar, where every strand of hair or drop of water is plumped, firmed, and rendered realer-than-real, like digital botox. But it wasn’t always this way. In the ’60s and ’70s, a pioneering artist named Will Vinton developed a cult following for his specific brand of strange, psychedelic animation using plasticine clay. He called the distinctly textured, highly tactile medium “claymation” and went on to open a well-respected animation studio that dabbled in TV, short films, and advertising. Who can soon forget the improbable but wildly popular R&B quartet the California Raisins Band, with their Emmy-winning TV special?

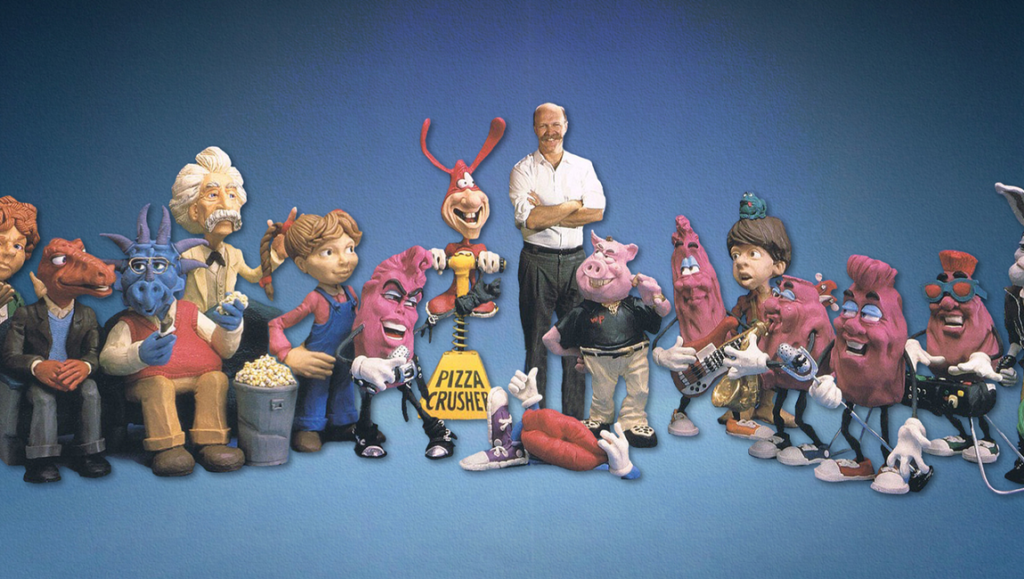

In his comprehensive new documentary ClayDream, writer and director Marq Evans offers viewers classic biographic fare as well as mesmerizing clips of Vinton’s early claymation shorts. With their dreamlike imaginative flourishes and stunning fluidity, these clips showcase Vinton’s artistic vision more accurately than anything a talking head could possibly put into words. Vinton, who harbored artistic (and commercial) aspirations to become the next Walt Disney, was based in Portland, Oregon, and the city’s long history of iconoclasm was a clear spiritual match for his wacky sensibilities.

Portland was also home to another artistically minded but significantly more cutthroat entrepreneur: Phil Knight, the founder of Nike and an early investor in Will Vinton Studios. ClayDream opens with footage of Vinton and Knight squaring off at a deposition, then takes a chronological view of Vinton’s career before focusing on the disastrous mismanagement that ultimately led to the studio’s demise, and a pathetic $50,000 payout to Vinton himself.

Along the way, Vinton experienced his fair share of success, including an Oscar for his early short film, Closed Mondays. But his artistic highs were shadowed by numerous personal and professional lows. His early artistic partner, Bob Gardner, felt sidelined by Vinton’s success and later committed suicide after many years of manic behavior, while his long-cherished dream of releasing a claymation feature film resulted in the misunderstood and critically panned The Adventures of Mark Twain. Evans makes clear — and Vinton is the first to admit — that his business acumen never kept up with his artistic aspirations. In one wince-inducing interview, Vinton reveals that he passed on an opportunity to sell his studio to the then-nascent Pixar. He also lost out on hugely lucrative licensing rights for the California Raisins, and his attempts at creating his own suite of licensable characters resulted in the underwhelming Wilshire Pig. Needless to say, plans for a theme park were scrapped.

But it was the debacle with Knight that ultimately sounded the death knell for Will Vinton Studios. As claymation saturated the market and business dried up, Knight acquired a majority stake in the company. Before long, Vinton was pushed out of the studio that was the sole source of his entire net worth and artistic legacy. There was also the presence of Knight’s son Travis, a wannabe rapper whose employment at the studio was written into the buyout contract. It all reeks of nepotism, though various interviewees are quick to point out that Travis had a genuine talent for animation. Incidentally, he became the studio’s next president — and (way to bury the lede!) renamed it Laika, the Oscar-nominated company behind Coraline and Kubo and the Two Strings. Neither Knight was interviewed for this documentary, though Travis’ own career certainly withstands scrutiny, despite its somewhat unsavory origins.

By all accounts, Vinton’s incredible optimism was both his downfall and his salvation. It allowed him to build a pioneering studio from scratch and weather the blows of critical failure and near-bankruptcy, even though his own lack of foresight was often the culprit. And eventually, he was able to find peace once the studio changed hands for good. By the time of his death in 2018 of multiple myeloma, a blood cancer, he had moved on to numerous other artistic pursuits. No longer an emotionally distant workaholic, he’d transformed into a loving and present father who realized that a legacy can take many forms.

Published as part of Before We Vanish — August 2022.

Comments are closed.