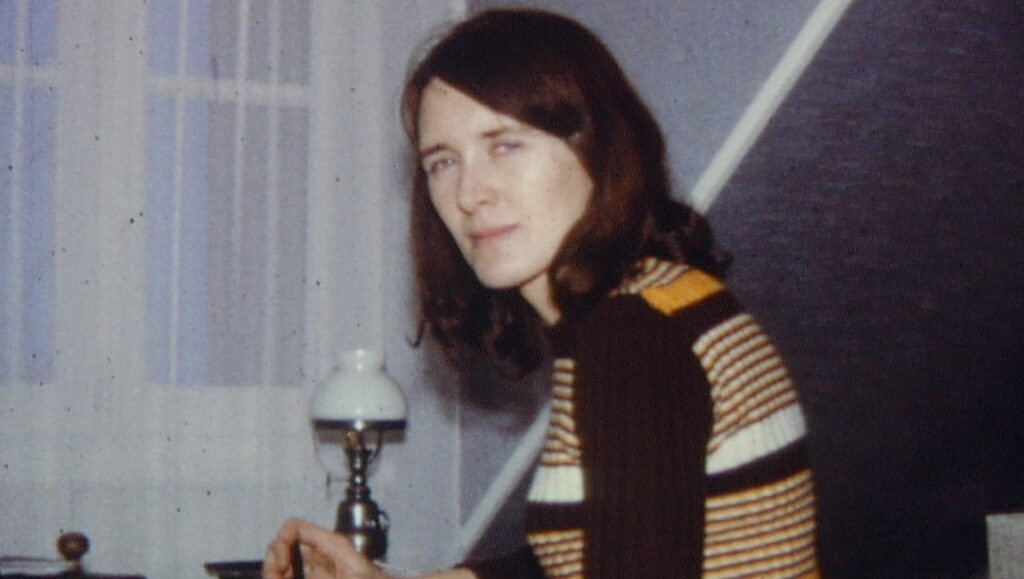

Step back while reading Annie Ernaux’s autobiographical opus The Years, and you will find yourself pausing a survey of a collection of photographs. These still images declared ephemera by the opening dictum “All the images will disappear,” and conjured to life by Ernaux’s ecstatic prose, are centerpieced through the work as remnants of her past woven into the broader twentieth-century fabric. To read Ernaux is to get swept from the shores of personal nostalgia into an ocean of collective experience, driven by the commanding power of her literary undercurrent. Recent years have seen an increased interest in adapting her work into film (Arbid’s Simple Passion, Diwan’s Happening), and her Nobel Prize win this year will likely further accelerate the trend, but The Super 8 Years exists peripheral to prior adaptations and is instead another type of project altogether. This collection of home movies, filmed in the 1970s by then-husband Phillipe Ernaux, collaged now by her son, director David Ernaux-Briot, and narrated by the author herself, is the same type of nostalgic artifact as the photographs mentioned moments ago. Sadly, this footage, pleasantly captured snippets of vacations in gorgeously soft Super 8, subdues the raw literary horsepower of Ernaux’s compositions, imprinting ease, both placid and banal, onto an author whose writing is anything but.

Annie Ernaux’s oeuvre, for those unfamiliar, is a ferocious type of memoir, critical of the nature of class, gender, memory, a writer’s inclination to seize these into language, and their relationship to the sociopolitical realities that swirl through past and present. As lofty as these ambitions appear, Ernaux balances such themes with incredible grace in books that punch far above their novella-sized weight class. Many familiar ideas emerge in The Super 8 Years as well, but in often watered-down forms. The vacation footage in question, amicable at a glance, much like The Years is peppered with political subtext: the stark colonialist divides of Moroccan resorts where tourists are gated off into safe zones, an inspiring trip to Chile preceding Pinochet’s coup, or the unsettled secrecy in communist Albania. Ernaux makes pointed observations ruminating on the tensions of her leftist politics and the distinctly bourgeois nature of these family getaways regardless of the locale, or the juxtaposition of her resounding feminism to the traditional gender roles penetrating her home life, but the film’s concept, entirely contained within this footage, seems to constrict her sharpest tendencies.

The Years feels orchestral, thrashing from one corner of the world to another, as a serpentine narrative of a woman’s awakening (sexual, political, and artistic) winds its melodic way through the thundering crescendos of headlines and social upheaval. In contrast, The Super 8 Years feels like a piece of bedroom pop, woozy, somnambulant, and, most disappointing of all, safe. Rather than having ideas stack and interlock, pulling past and present together, the film’s structure promotes a linearity antithetical to Ernaux’s larger project, sluggishly lingering thoughts bound by the pull of time. The film’s movements locked to the ever-advancing reels have a stilted quality, producing either redundancies — white mountain tops blushing with pink hues are beautiful to behold, but the grandeur starts to slip the longer image and narration ogle them — or cliches: a bullfight sequence in Spain finds the footage slowed to a crawl, leaving us to watch the ceremonial violence in hushed reverie. It’s not surprising then that the most thrilling moment in the film arrives when the reel ends but the narration continues, and there in the darkness, at last, Ernaux holds us in her grasp, having wrested control. Here she shows us just a fragment of her power to pause time and wrench it backward with her words alone, “words leaping up like the buried water jets… which spray when you walk across them.” Words which, like the images, will be “eliminated” in time as well, but not yet, not quite yet, and for a brief moment, when the images return, they seem to bend to her will.

Comments are closed.