Writing for the New York Times in 1997, film critic Janet Maslin called Harmony Korine’s directorial debutGummo the “worst film of the year” — no small claim for a year that saw some stiff competition from the likes of Jack Frost, Beverly Hills Ninja, and Jungle 2 Jungle. The reaction is perhaps unsurprising since, right off the bat, Korine puts his most provocative foot forward by interrupting the grainy home videos and eerie voiceover of the opening credits with a teenager drowning a cat in a water-filled barrel. It’s a jarring, but fitting, introduction to the squalid experimentalism through which the fresh-faced writer-director portrayed the town of Xenia, Ohio, a white trash stronghold recently ravaged by a tornado. The characters that inhabit Xenia run the gamut from eccentric to psychopathic: a man pimps out his disabled sister, two skinhead brothers have a fistfight in their kitchen,foul-mouthed children hurl racist and homophobic insults at a boy wearing bunny ears, and two boys carry around garbage bags filled with dead cats. It’s an atrocity exhibition presented in an unobtrusive vérité style with prolonged displays of rural decay that sometimes borders on the unwatchable.

Korine’s unflinching artistic instincts were apparent when Larry Clark adapted his screenplay for Kids in 1995. The New York City tale of youthful depravity shocked and intrigued audiences with its loose storytelling form and frank depictions of sex and drug abuse, but with Gummo, the then-24-year-old former skateboarder decided to do away with narrative entirely. In an interview with fellow director Werner Herzog — both a fan of and a major influence on the young filmmaker — Korine had this to say about the state of film in the mid-to-late ’90s: “When I look at the history of film […] and then look at where films are now, I see so little progression in the way they are made and presented, and I’m bored with that […] With Gummo I wanted to create a new viewing experience with images coming from all directions.” His dissatisfaction with the medium’s creative stagnation is felt in the feverishness of the film’s audiovisual assault, a formal approach where every frame is overloaded with information.

Revisiting the film 25 years later, Gummo not only retains every bit of its darkly enticing appeal, but it also makes clear Korine’s status as a genuine cultural force. Although he was, and sometimes still is, dismissed as a cheap provocateur — Maslin wasn’t the only critic who was less than impressed with what he had to offer — his profound influence on contemporary pop aesthetics cannot be overstated. Another admirer of Korine’s, Gus Van Sant, praised the film’s “sophisticated and refined cinematic dialogue of modern cultural influences.” This cinematic dialogue has cast a long shadow — as the film’s cat-killing main characters Solomon (Jacob Reynolds) and Tummler (Nick Sutton) ride their bikes down a hill, looking for prey, the scene is accompanied by the thunderous stoner metal riff of Sleep’s “Dragonaut,” and the bizarre underclass Americana that the short vignette evokes has retained so much of its aesthetic staying power that, more than two decades later, it’s easy to picture a similar scene playing out to the sinister trap sounds of Migos or Kodak Black in an episode of Atlanta, or couched within the upside-down-cross pranksterism of an early Odd Future music video.

While Korine’s acute awareness of the zeitgeist would eventually lead him to godfather the Tampa-core genre with his oneiric black comedy crime thriller Spring Breakers, Gummo remains his purest artistic statement, the epicenter of all of his creative endeavors, the fount from which every other work in his oeuvre springs. The Dogme 95 drama Julien Donkey-Boy, the low-rent scuzzfest Trash Humpers, and the melancholy outsider dramedy Mister Lonely all boast DNA that can be traced back to Korine’s first film. Even his absurdist novel, A Crack Up at the Race Riots — an attempt at “the Great American Choose Your Own Adventure Novel” — trades in the same bleak, fragmented, quasi-comedy of Gummo. In his interview with Herzog, Korine elaborates: “It goes back to [Charles and Ray] Eames and [Isamu] Noguchi talking about a unified aesthetic. You can make movies, write books, do a ballet, and sing opera, but it’s all part of the same vision.”

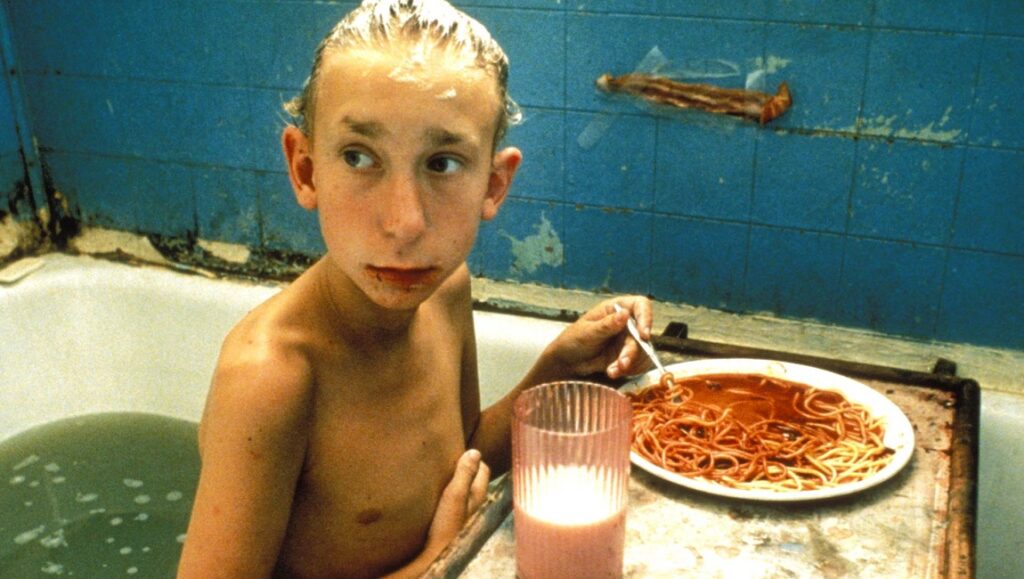

There’s a crucial piece that the director’s lesser imitators, critical naysayers, and quite a few ignorant fans miss, however: in spite of the depravity it depicts, in spite of the borderline exploitative relationship it itself has with its subjects, there is a quiet tenderness to Gummo that exists alongside the nihilistic radicalism that permeates it. Korine isn’t interested in shocking the audience as much as he’s trying to place them squarely in a milieu that they (most likely) know nothing about. And yet, the famous scene of Solomon eating spaghetti and drinking milk in a bathtub filled with filthy, brown water resonates exactly because of how familiar and mundane it feels — a young boy sitting in a dirty bathtub, messily eating his dinner, while his mother tries to get him clean. It’s decidedly odd — for some reason, a strip of fried bacon is taped to the bathroom wall — and it’s slightly uncomfortable, but seen through Korine’s eyes, the scene also becomes strangely touching, a snapshot of normalcy amidst a world that has been thrown into disarray. It confronts us with the fact that the people we tend to look down on are, in fact, human beings, too — maybe that’s where the crux of Korine’s provocation truly lies.

Published as part of InRO Weekly — Volume 1, Issue 1.

Comments are closed.