When Kasi Lemmons made her directorial debut with the 1997 Southern Gothic masterpiece Eve’s Bayou, it likely wouldn’t have occurred to people that she would eventually be reduced to working on by-the-numbers fare like I Wanna Dance with Somebody, the latest cinematic equivalent of a Wikipedia article — this one based on the life of Whitney Houston. Lemmons’s film, adapted from a script by Bohemian Rhapsody screenwriter Anthony McCarten, is a slipshod attempt at cleaning up the legendary songstress’ image and legacy, all while scrubbing away the messier aspects of her humanity. As such, even I Wanna Dance with Somebody‘s decision to not focus on Houston’s scandal-ridden later years feels cynical, a transparent effort by her estate, which participated in the project, not to rehabilitate her as much as make her marketable again — a process which is already in motion, with a line of cosmetics and a variety of Funko POP! Figurines.

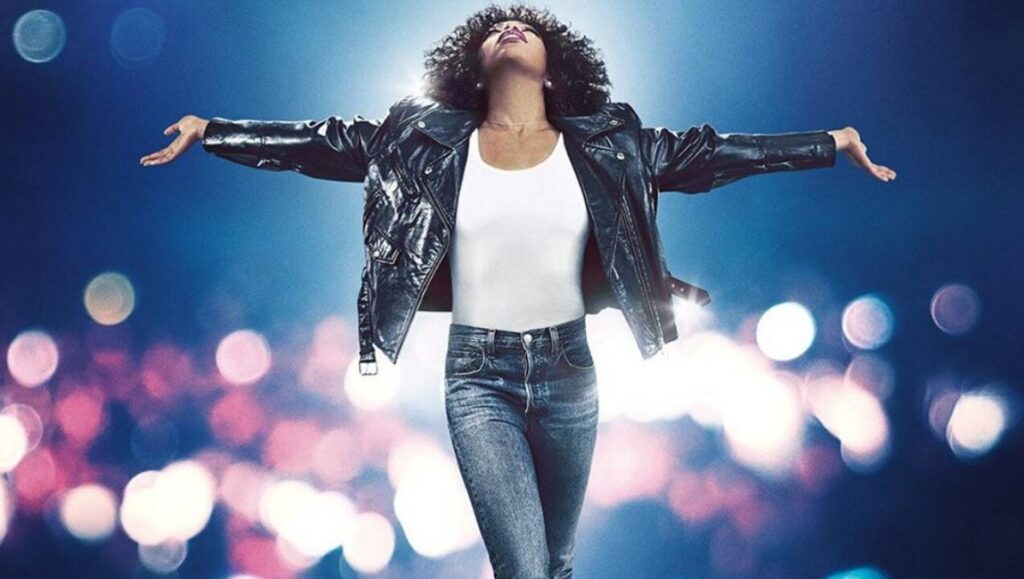

It’s unfortunate, but the rote filmmaking on display here couldn’t be further removed from the layered sensitivity that has marked Lemmons’s previous work — even her somewhat formulaic 2019 Harriet Tubman biopic Harriet drew out some memorable performances from its cast. I Wanna Dance, by contrast, plays more like a glorified clip show where none of the actors are given room to breathe. Naomi Ackie manages to wring a surprising amount of depth out of the clichéd material, but her co-stars, including Stanley Tucci and the woefully underemployed Ashton Sanders, are completely suffocated under a barrage of shoddily conceived and assembled scenes, filled with tropes that would have felt stale a decade ago.

The film opens at the 1994 American Music Awards, where Whitney Houston (Ackie) is preparing to deliver her famous medley of “I Loves You, Porgy,” “And I Am Telling You I’m Not Going,” and “I Have Nothing,” obviously setting up what will come to represent the peak of her musical career — her own 1985 Live Aid moment, so to speak. After the title card, the audience is taken to 1983, where a young Whitney dazzles a New Jersey church congregation with her raw vocal talent. Led with a firm but loving hand by her mother, Cissy Houston (Tamara Tunie) — an accomplished singer in her own right — Whitney eventually manages to secure a record deal after her extraordinary performance of George Benson’s “The Greatest Love of All” impresses record producer Clive Davis (Stanley Tucci). However, the ensuing success proves difficult to navigate, and Whitney is forced to contend with accusations of selling out, her overbearing father John (Clarke Peters), who also works as her manager, and a strained and abusive marriage to R&B singer Bobby Brown (Ashton Sanders).

Much like he did with Freddie Mercury — Bohemian Rhapsody played down the Queen frontman’s queerness in favor of a more flattering portrayal of the surviving band members, another example of an estate working to protect its own bottom line — McCarten here flattens Houston into an uncomplicated, easily digestible avatar, and as such, her same-sex relationship early in life, as well as her internalized homophobia, are included but insufficiently explored. Similarly, her spiritual development — admittedly unhip subject matter that few contemporary filmmakers are willing to engage with — is barely given the time of day, in spite of her having been brought up in the church and the film’s penchant for asking characters to use the Bible to rationalize their behavior. Instead, we get predictable gestures, transparently designed to appeal to modern sensibilities: “Yes, I’m exhausted. All Black women are exhausted,” complains Houston in a particularly unnatural exchange.

While I Wanna Dance‘s hagiographic treatment mostly relies on the power of the music (or, more specifically, its subject’s soaring voice) to generate its few captivating moments, it fails to truly capture the transcendent beauty that made Houston’s legendary melisma such an enduring part of popular culture. The singer’s legacy needed a corrective after years of being defined by her premature, drug-related death, and regardless of whatever financial motivations led to it, the choice to ultimately not frame her life as mere tragedy, particularly given the genre, is indeed commendable. But it’s hardly an excuse for crafting a film that is ultimately this lifeless and dull.

Published as part of InRO Weekly — Volume 1, Issue 1.

Comments are closed.