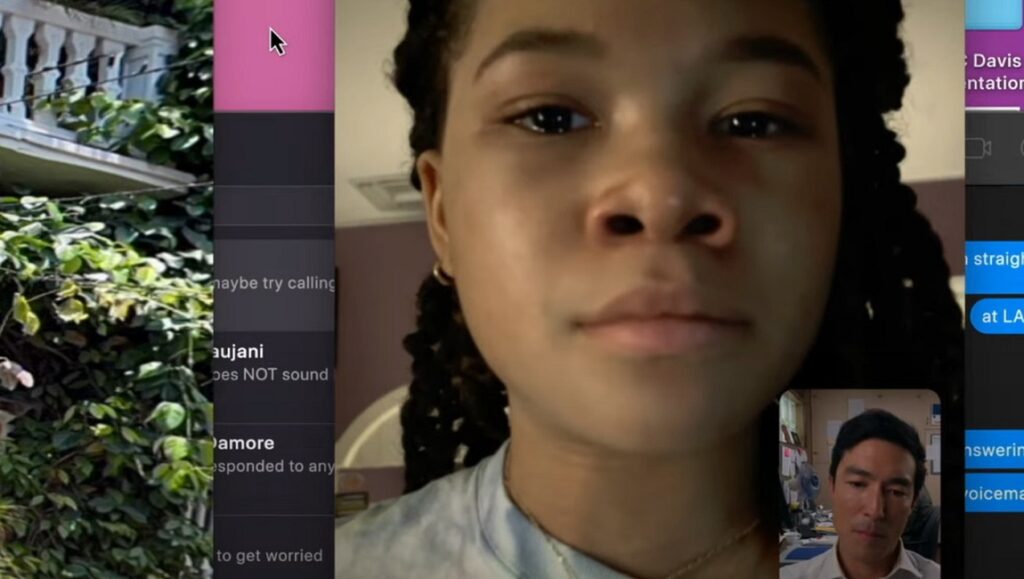

Existing since the early 2000s, the Screenlife genre finally found box office success in 2014 with the release of horror flick Unfriended, in which a demonic spirit stalks a group of friends. But surprisingly, such boffo numbers did little to convince Hollywood to fully embrace the format, leaving low-budget indies to pick up the slack. Indeed, one of the only follow-ups to make any sort of cultural dent was 2018’s Searching, in which a single dad desperately tries to find the whereabouts of his missing daughter. Missing, the latest stab at Screenlife, is billed as a “spiritual sequel” to Searching, which apparently means that it takes place within that earlier film’s universe despite never once alluding to the events that transpired five years ago. In reality, Missing is more like the inverse of Searching, with a teenage girl named June (Storm Reid) frantically tracking down any clues that might lead to the whereabouts of her mother, Grace (Nia Long), who went vacationing with current boyfriend Kevin (Ken Leung) one week prior and seemingly vanished into thin air.

While this genre may seem to have built-in limitations, one thing it has always had going for it is, ironically enough, the speed with which technology changes. Look no further than the aforementioned Unfriended, which today, less than a decade later, already feels like a relic from another era, its lo-fi computer cameras and obsession with Facebook feeling borderline quaint in retrospect. Film is nothing if not a reflection of both the time period in which it was made and the larger culture that created it, and Screenlife is bracing in its pure embodiment of this tenet. Host (2020), made at the height of Covid quarantine, took full advantage of our society’s budding love/hate relationship with Zoom, while Dashcam (2021) employed the titular technology to comment on police brutality — as dunderheaded as the messaging might have been. Missing is certainly of the moment in that regard, utilizing everything from Instagram to Siri to Ring doorbell cams to bring its central mystery and resulting investigation to life. It’s our familiarity with such tech that grounds Screenlife films in a way that similar thrillers can barely muster. After all, Missing isn’t up to anything new story-wise: A regular joe tries to uncover the clues that will allow them to solve some nasty bit of foul play. Indeed, it’s not much of a stretch to imagine that Hitchcock himself would get a kick out of the genre, the majority of its features amounting to what the filmmaker was up to 75 years prior in the likes of Rear Window and North by Northwest.

Unfortunately for audiences, Missing’s writer-director duo of Nicholas D. Johnson and Will Merrick — both of whom were editors on Searching — are no Hitchcock, and while the movie has more than its fair share of plot twists up its sleeve, the pair never attempt anything even remotely novel with the format on a visual level. So much of the action is simply shot through a laptop camera, with the occasional use of an iPhone or security footage thrown in for a little extra flavor. Those expecting anything along the lines of Unfriended, in which the downloading of an MP3 was used to craft maximum tension, should look elsewhere, as this film is so obsessed with Google and Gmail that it nearly feels like a two-hour long advertisement. Admittedly, Johnson and Merrick do have some fun with the idea that its teenage, tech-savvy protagonist could easily hack into the accounts of her analog, middle-aged guardians due to their use of the same password for every website, but there comes a point where such “reality” also feels like a crutch, an easy way to offer non-stop dumps of exposition and backstory.

Johnson and Merrick also cheat, more than one or two times, two when it comes to the limitations of the format itself, supplying repeated close-ups that are never achieved through the internal action of its characters. While this kind of observation may feel like nit-picking, details of this nature stick out like a sore thumb in a genre where visual integrity is perhaps the essential quality, and where there exists such an insistence on realism. Also problematic is that the film writ large is ugly as sin, as if nobody involved would own a piece of technology that possessed high-definition capabilities. Missing is ultimately nearly identical to Searching, then; involving enough on a moment-by-moment basis, but failing to utilize its chosen form in a way that feels intrinsic to its generic plot. Indeed, both movies come across like scripts from a network crime procedural that were technologically retro-fitted after the fact — not to mention that both completely whiff their endings, compelling events building to the most obvious conclusions possible. The one thing truly missing from Missing is a reason (beyond profits) to justify its existence, littered small pleasures be damned.

Published as part of InRO Weekly — Volume 1, Issue 3.

Comments are closed.