The post-independence era was a turbulent one for the small island nation of Jamaica. Having gained freedom from the British in 1962, the following decade of economic growth was also marked by increased inequality and escalating urban violence. It’s against this backdrop that writer-director Perry Henzell and co-writer Trevor Rhone decided to bring the story of notorious Jamaican outlaw Ivanhoe Martin — known by his nickname Rhyging (the Jamaican Patois word for “raging”) — to the screen. After being shot dead by police in 1948, Rhyging, who is often described as the original “rude boy,” grew into a sort of folk legend for many poor Jamaicans who found in him a rebellious antihero who stood up against the colonial and capitalist order — a complex admiration not dissimilar to the one enjoyed by early-20th-century European illegalists like Jules Bonnot.

Henzell and Rhone’s script — which began life under the working title Rhyging before they settled on the implicit fatalism of The Harder They Come — updated the rudy’s story to the 1970s, and the two decided to cast reggae singer Jimmy Cliff in the lead role. Cliff, who had no prior acting experience outside of school plays, had seen his star rise throughout the back half of the ’60s, and his 1970 single “Vietnam” even earned the praise of Bob Dylan, who called it the best protest song he’d ever heard. The musician’s natural charisma in the lead role wouldn’t be the only thing to contribute to the first Jamaican feature film’s lasting legacy, however, as its iconic soundtrack — featuring tracks from Desmond Dekker, Toots and the Maytals, and Cliff himself — is widely credited with popularizing reggae music internationally.

Composed for the film, Cliff’s infectious title song formed a defiant yet grim counterpoint to the aspirational “You Can Get It If You Really Want,” which plays over the opening credits, anticipating the tragic end to the badman protagonist’s nihilistic rebellion. “So as sure as the sun will shine / I’m gonna get my share now, what’s mine / And then the harder they come / The harder they fall, one and all,” goes the song’s chorus, the fictionalized Ivanhoe Martin — “Ivan” for short — unwittingly prophesying his eventual downfall during a recording session. But like the films that inspired it — Django, which makes an appearance during a rowdy screening in Kingston; The Wild Bunch; Bonnie and Clyde — The Harder They Come trades in stylishly gritty action fireworks, even as it anticipates the bleak fascination it, or more specifically its main character, will inspire. For instance, when the fugitive Ivan attempts to gun down his former boss, José (Carl Bradshaw), chasing him through a Kingston slum, he is quickly surrounded by laughing children, eager to get a glimpse of the charismatic desperado.

Even more obvious is Henzell’s framing during the Django screening: youthful, curious faces, illuminated by the silver screen, look on in awe as Franco Nero’s titular character guns down rows of menacing, red-hooded enemies with a machine gun, collectively erupting in cheers as his adversaries’ dead bodies hit the dusty desert ground. When an audience member gets a little too caught up in the narrative and worries out loud about Django’s survival, the brash José mockingly asks him, “You think hero can dead ’til the last reel?” — a glib seen-it-all-ism that, in a moment of sly subversion, will prove to be just as prophetic as the title track.

Ivan’s transformation from awkward “country bwoy” to murderous gunslinger is a radical one. Arriving in Kingston with wide-eyed naïveté and half a dozen bags — the entirety of his earthly possessions — he is immediately robbed blind by a vulturous street vendor and forced to face his brusque, city-dwelling mother with nothing but vague hopes of making it as a singer. Unable to stay with her, he eventually finds a job doing menial work for a Christian minister (Basil Keane), but soon begins pursuing the preacher’s young female charge, Elsa (Janet Bartley). After spending most of his time reading comic books and issues of Playboy, not to mention using the church to rehearse his secular tunes, the bohemian Ivan is dismissed, and an argument with a former colleague escalates into a knife fight, transforming Ivan’s eyes from mellow and friendly to gleefully sadistic for the first time.

After being sentenced to a brutal whipping by a judge for slashing his opponent’s face, Ivan becomes fully determined to make it as a reggae artist, but exploitative music industry practices, as well as a resentful record executive, move him to accept a side hustle as a drug runner. The runs go smoothly at first, but when an approaching police officer triggers a flashback to the corporal punishment he received, the traumatized Ivan guns down the cop, effectively sealing his fate. It’s not only the moment that gives birth to the near-mythological black hat, a kind of trauma response which leaves the charmingly gawky Ivan behind to make way for the legendary dual-wielding gunman, but also where the film itself transforms from a neorealist travelogue into a guns-blazing crime thriller.

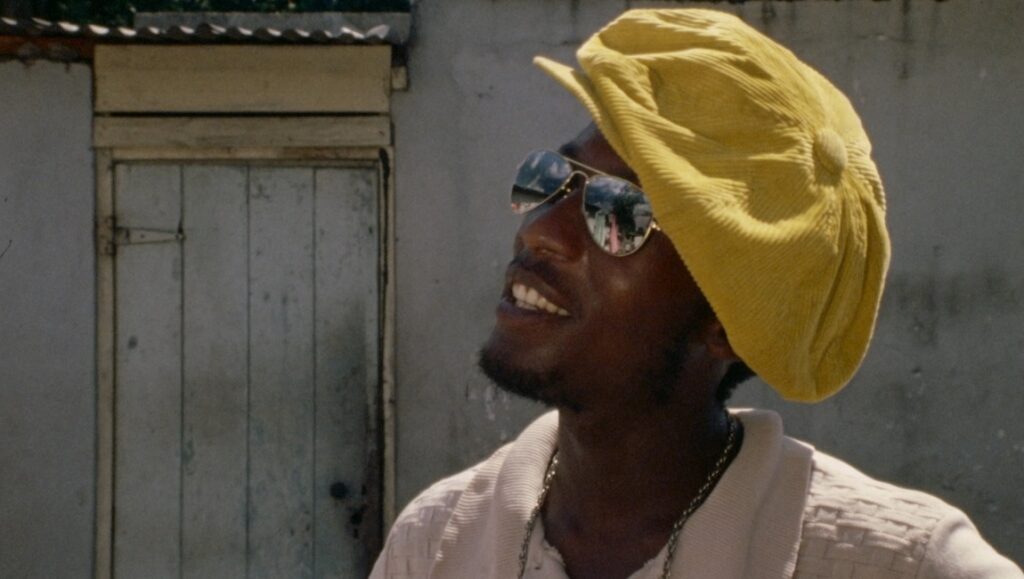

Before the third-act eruption, The Harder They Come simmers with rich textures and barely-contained sensuality, perhaps best exemplified by a sequence during which the religious ecstasy of a church congregation resembles the more carnal ecstasy of sex — sweaty churchgoers contort their faces as they shake, twist, and even tumble over in suggestive elation. Elsa, in the midst of the wildly gyrating mass, suddenly has blissful sexual fantasies of herself and Ivan, their naked bodies covered in the wet of a surrounding ocean. It’s a provocative scene, one where lust seems to trigger something akin to a spiritual vision, and the sparkle and shine of her daydream lend the images a paradisiacal quality, the two lovers becoming Adam and Eve-like figures in the young romantic’s mind. But even the film’s sexuality becomes more lurid following Ivan’s inciting murder. Far removed from Elsa’s picturesque visions, Ivan’s newly-discovered ruthlessness leads him into a tryst with José’s girlfriend — before engaging the police in a deadly shootout dressed only in his underwear. In fact, even though he’s on the run, his hedonistic hunger grows so insatiable that he throws caution to the wind, and instead opts to steal cars, buy fancy clothes, and even pose for a photoshoot. Pistols in hand, Ivan swaggers in front of the camera, mimicking Spaghetti Western hard-asses and building his own myth in the process.

The photoshoot plays an interesting role in the film. For one, it epitomizes just how brazen Ivan has become, refusing to lay low and later sending his stylish portraits to newspapers. For another, it interrogates history, self-invention, and the very medium of photography itself. Ivan flaunts his elusiveness by, paradoxically, making himself more visible — he spray-paints “I WAS HERE BUT I DISAPPEAR” all over Kingston, taunting the police — mirroring contemporary news reports of Rhyging’s criminal activities, dramatically describing him as a “phantom killer” with a propensity for disappearing as quickly as he appeared. Even though he was widely reported on as he shot his way into folk hero status, photographs of Rhyging are rare, and the few that exist have deteriorated to the point of indecipherability, his image largely living on in the cultural imagination.

Cliff’s portrayal almost functions as yet another instance of Rhyging suddenly reemerging after having, in a sense, “disappeared into the dark,” as the Kingston-based Daily Gleaner so aptly described his seemingly miraculous vanishing act after committing a murder. The dissemination of images has been an important element through which history is understood, and there’s a lot of ink to be spilled about how these processes tend to favor certain groups of people over others — photographs of Billy the Kid or Jesse James are far better preserved, their moral character being no less dubious than Rhyging’s. As such, The Harder They Come stands not just as a fiery crime film, but also as a necessary corrective to a neglected photographic history of Jamaica.

The film was a sensation upon its Jamaican release, with showtimes regularly being overrun by enthusiastic filmgoers who, in an era of worldwide political upheaval and widespread anti-government sentiment, were thrilled to see the famous criminal finally come to life in a way he hadn’t been allowed to before. Even though the impact of its soundtrack has somewhat overshadowed Henzell’s debut, it hasn’t lost an iota of its radical power. Henzell himself has downplayed Rhyging’s status as a folk hero — in a 1988 television interview, he said, “[Rhyging] was just seen as a guy who created a lot of excitement… He’s a character, and people recognized that” — but his visceral take on the story nonetheless ensured that the myth will live on for generations to come.

Part of Kicking the Canon — The Film Canon.

Published as part of InRO Weekly — Volume 1, Issue 6.

Comments are closed.