Since his breakout 1997 film Xiao Wu, Jia Zhangke has emerged as one of the most gifted artists chronicling life in 21st-century China. Three of his earliest films — Xiao Wu, 2000’s Platform, and 2002’s Unknown Pleasures, all of which were made outside China’s studio system — form a loose, low-budget trilogy portraying life at the bottom in an emerging superpower. Jia didn’t abandon that focus when he made the leap to bigger budgets and State approval — 2013’s A Touch of Sin, for instance, is also unflinching in its social criticism — but nevertheless, Unknown Pleasures especially captures the crushing ennui of the early 2000s era.

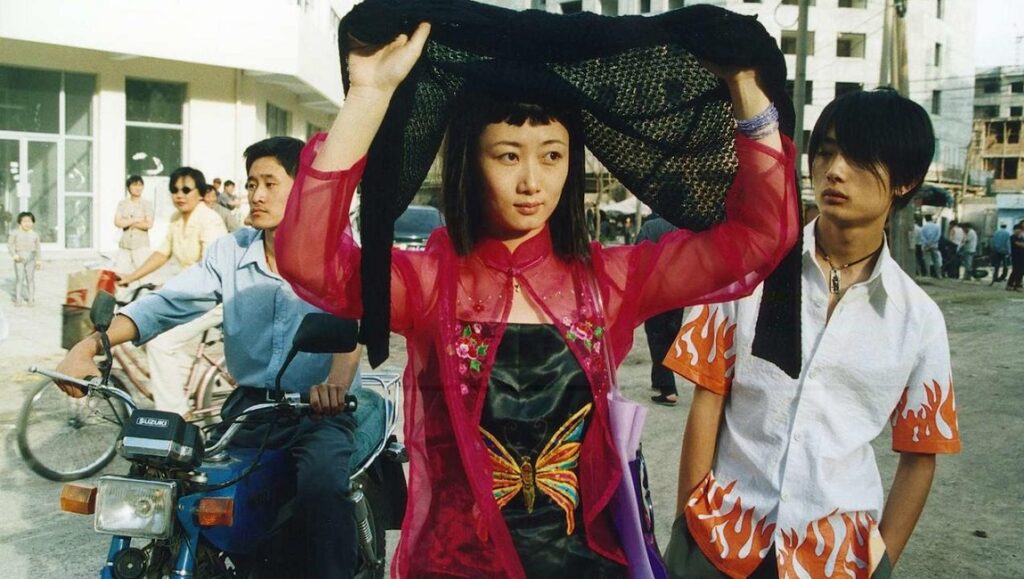

The film follows three disaffected young people as they navigate life in the changing People’s Republic. Unlike Platform — a sprawling, elliptical, and unwieldy reflection on the rapid social changes from the late 1970s to the early ’90s — Jia’s succeeding film is a more concise and decidedly contemporary tale of alienated youth. Xiao Ji (Wu Qiong) is a reckless scoundrel who falls in love with Qiao Qiao (Zhao Tao), a singer, dancer, and sex worker who performs at promotional events put on by her gangster boyfriend (and pimp) Qiao San (Li Zhubin). Xiao Ji’s best friend, Bin Bin (Zhao Wei Wei), meanwhile, struggles with depression caused by unemployment and the scorn of his ball-busting mother (Bai Ru), who is a follower of the Falun Gong church.

Xiao Ji and Bin Bin spend most of their time haunting pool halls by day and drowning their depression in nightclubs by night. The loud techno music, which remixes iconic pieces of Americana such as Dick Dale’s surf-rock spin on “Miserlou,” signifies the encroaching Western influence which coincided with the increasing liberalization of China’s markets, a development which culminated in the PRC joining the World Trade Organization. Jia roots Unknown Pleasures in the present by including contemporary news reports flickering across discolored, bulbous television sets — a group of textile factory workers are seen celebrating the announcement that the 2008 Olympics will be held in Beijing — and a pervasive sense of internet-era detachment, exemplified by a character nonchalantly asking if the Americans had invaded China again when she hears a loud explosion destroy the local textile factory.

Arguably, Unknown Pleasures’ portrayal of late-capitalist malaise could be read, if not as explicitly Marxist, then at least as a left-wing, anti-capitalist critique of globalization. The nature of Jia’s social criticism, however, is somewhat surprisingly far more conservative in character. “In Unknown Pleasures, young people lack discipline,” said the filmmaker in the film’s production notes. “They don’t have any goals for the future. They refuse all constraints. They run their own lives and act independently. But their spirit is not as free.” Indeed, the lives of his central trio are very much defined by the mass media that surrounds them, while Chinese culture has faded into insignificance. Their search for freedom has, ironically, presented them with more limitations — in the words of Neil Young: “And I know we should be free / But freedom’s just a prison to me.”

In what is perhaps the film’s most interesting aesthetic choice, Jia sets Unknown Pleasures in a crime-ridden, rubble-littered wasteland — heightened significantly from Platform‘s comparatively less seedy post-industrial setting — a backdrop that invokes a kind of post-apocalyptic reflection of the spiritual decay of post-Maoist China that Jia laments. The characters seek to escape their hopelessness through shallow hedonism that they mimic from the Western movies and TV shows that have recently become accessible to them. While sitting in a restaurant, Xiao Ji, eager to impress Qiao Qiao, tells her about his vague ambitions as an outlaw while making reference to Pulp Fiction‘s opening scene, quoting its dialogue and pointing his finger (mimicking a gun) at the other customers. Jia punctuates the scene with a rare moment of overt stylization, whipping the camera around in a blur to transition the scene to a nightclub.

This stylization is remarkable because Yu Lik-wai’s consumer- grade digital cinematography otherwise radiates pure home- movie transience, imbuing the film with something more ephemeral — an object found and observed, rather than consumed. Unknown Pleasures‘ musings on the purgatory at the end of history recall Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Millennium Mambo, released the year before, but Jia’s vision of neoliberal Weltschmerz is a lot bleaker than Hou’s. While Millennium Mambo‘s Vicky (Shu Qi) addresses the audience from the future of 2011, implying some form of resolution and development for the adrift young woman, Jia cuts his sparse narrative short with Bin Bin being made to sing for the cops who arrested him after a failed robbery attempt. The last glimpse the audience gets of him is standing in a police station — lost, humiliated, doomed to languish in purgatory forever.

Part of Kicking the Canon — The Film Canon.

Published as part of InRO Weekly — Volume 1, Issue 13.

Comments are closed.