Seijun Suzuki made his name with a string of Nikkatsu-produced genre flicks — The Naked Woman and the Gun (1957), Voice Without a Shadow (1958), Man With a Shotgun (1961) — but is probably best known to contemporary audiences for his yakuza films. A relatively inhibited take on American gangster noirs quickly evolved into a kaleidoscopic assault on the form that made him both beloved and infamous, with what’s now his most acclaimed work — 1967’s eclectic, satirical yakuza classic Branded to Kill — initially landing as a critical and commercial failure, and leading to Suzuki’s dismissal by Nikkatsu, for making “movies that make no sense and no money,” according to the filmmaker. This then led Suzuki to successfully sue the production company, but the ordeal cost him a decade-long blacklisting.

Though Suzuki’s freewheeling cinematic sensibilities can actually be traced all the way back to his debut film, 1956’s Victory is Ours, the first genuine flashes of his trademark style appeared in the 1958 crime film Underworld Beauty. Not only was this the first of his films credited to Seijun Suzuki (as opposed to Seitaro Suzuki, his birth name), but it also featured an unorthodox visual creativity — cleverly obscured nudity; deep, mysterious shadows; creepy mannequin set design — which was nevertheless noticeably restrained by Nikkatsu’s expectations of commercial viability. Take Aim at the Police Van (1960) and Detective Bureau 23: Go to Hell, Bastards! (1963) can be similarly described. But then came Youth of the Beast, which marked a true turning point for the filmmaker.

One of four Suzuki films released in 1963, Youth of the Beast saw the auteur truly embrace his playful pop artistry for the first time — even Suzuki himself called it his “first truly original film.” The plot is essentially a spin on Kurosawa’s 1961 samurai film Yojimbo, wherein a wandering ronin, Kuwabatake Sanjuro (Toshiro Mifune), infiltrates the organizations of two opposing crime bosses struggling for supremacy to bring peace to a small village. But unlike Kurosawa’s classic, Suzuki’s crime tale has no place for such noble aims. Joji “Jo” Mizuno (the famously chipmunk-cheeked Joe Shishido) is an ex-cop driven solely by revenge. Having been wrongfully convicted of embezzlement, the newly released Jo becomes singularly focused on avenging the murder of his loyal former partner, whose death was staged to look like a lover’s suicide.

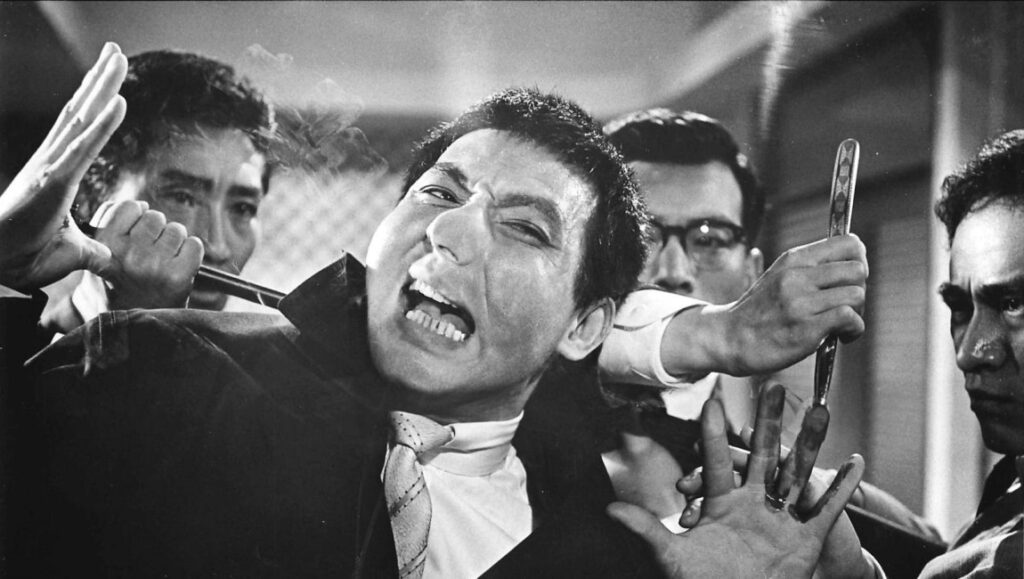

Jo’s pursuit of “justice” becomes a relentless, violent, and slyly comical odyssey through Kobe’s criminal underworld. Although 1966’s Tokyo Drifter would mark Suzuki’s first identifiably deconstructionist take on the genre, Youth of the Beast scans as similarly satirical. The film occupies a space between straightforward gangster film homage and Godardian pranksterism, amplifying genre tropes to near-absurd levels with increasingly convoluted violence, plot machinations, and set pieces — at one point, Jo disposes of his adversaries while hanging upside down from a chandelier — while occasionally pushing things into the realm of the avant-garde. For every blade violently shoved under a fingernail, there is a shot of radiant red flowers illuminating the otherwise black-and-white frames of the film’s intro. And Suzuki’s farcical tough-guy introduction for Jo — he beats up young delinquents before heading to a club to drink and beat up some more people — feels like a purposeful escalation of Breathless‘ Bogart-obsessed main character, Michel (Jean-Paul Belmondo).

Youth of the Beast’s gritty textures don’t rival Tokyo Drifter‘s arresting production design. But Suzuki still provides his share of striking images, such as when Jo invades the office of crime boss Shinzuke Onodera (Kinzo Shin). The head honcho’s office walls are illuminated by images of American and Japanese B-movie gangster melodramas — the kind of films that Suzuki was slowly but surely leaving behind. (Incidentally, Onodera, as well as his rival Tetsuo Nomoto (Akiji Kobayashi), are depicted as weaselly, bottom-line-obsessed businessmen, far removed from the honor codes often employed to romanticize Japanese organized crime.) This juxtaposition ultimately acknowledges the framework that the film — for all its clever subversions — operates within, obscuring the visceral violence that ensues by calling attention to its artificiality.

This unsentimental, stylized approach would prove influential on filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino, Park Chan-wook, John Woo, and Takashi Miike, whose genre efforts often echo Beast‘s elaborate brutality. Even Scorsese might have looked to Keiko’s (Naomi Hoshi) agonizing junkie floor crawl for The Wolf of Wall Street‘s infamous Quaaludes scene. Suzuki’s later, more surreal efforts overshadow the legacy of the first true Suzuki original, somewhat, and he remains tragically under-discussed as a talented dramatic filmmaker (1964’s Gate of Flesh and 1965’s Story of a Prostitute rank amongst his best work). But it’s with Youth of the Beast that his anarchic vision truly snapped into focus, and converged with a searing poignancy, felt in its ending: after the antagonist finally dies a horrible, razor blade-related death, Jo succumbs to despair and has a vision of a grayscale graveyard, where flowers once again gleam with red-hot menace.

Published as part of InRO Weekly — Volume 1, Issue 16.

Comments are closed.