British director Charlotte Regan’s feature debut, Scrapper, is a vibrant and charismatic film on the joys and heartbreak of adolescence and newfound fatherhood. Set and shot in the Limes Farm estate in Chigwell, Essex, Regan’s film clearly locates itself within Britain’s filmic legacy of gritty kitchen-sink dramas — the only exception being that Scrapper is filled with highly saturated colors, crafty working-class humor, and an infectious brightness that recalls the magical charm of Sean Baker’s The Florida Project and Joe Gilgun’s working-class comedy series, Brassic.

Scrapper centers on 12-year-old Georgie (Lola Campbell) as she raises herself up in a council estate after the death of her mother to illness. Not wanting social workers to find out that she has been left unattended, Georgie invents an uncle named Winston Churchill (a testament to her naïveté) and forces the corner shop owner to pre-record Churchill’s pleasantries for when the workers do their phone check-ins. She also spends most of her spare time with her best mate, Ali (Alin Uzun), stealing bicycles and fencing their parts for pocket money. By all accounts, Georgie is a self-assured, precocious, and resilient girl who cleverly navigates the adult world, fully believing that she can make it alone. And maybe she just can.

But we are also first introduced to Georgie as she arranges an empty house back to the way her mother has left it. She cleans the dishes, meticulously vacuums the floor, and stubbornly refuses to kill a spider because it was there before her mother died. While Georgie puts up a cheeky front to everyone, Scrapper lets us know that this is a girl who is trapped in stasis, unable to move on from the immensity of her grief. The wall that Georgie builds to protect herself from potential hurt, too, is reflected through her frantic and paranoid attempts to keep her dead mother’s bedroom locked. Behind the mystery door lies a tower made out of scrap metal and errant bicycle parts. The tower is small and incomplete. But it leads to somewhere bigger, like heaven.

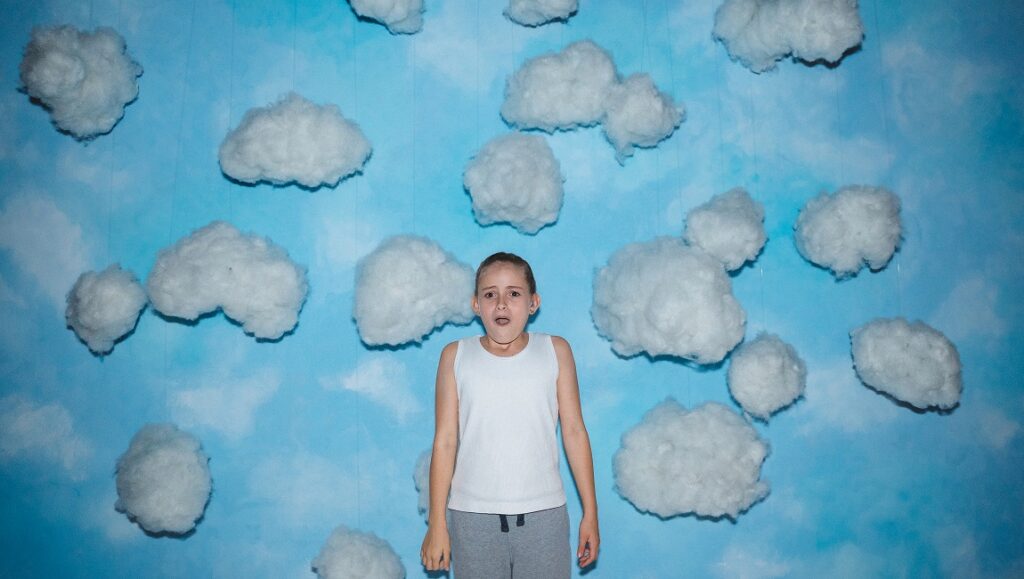

Georgie’s solitary circumstances change when her deadbeat father, Jason (Beach Rats’ Harris Dickinson), unexpectedly turns up and demands to live with her. Predictably, Georgie gradually warms up to Jason, who grows up and learns how to care for someone besides himself. In return, Georgie is allowed to be a child who simply misses her mother. Where Scrapper shines is its commitment to portraying grief from the complicated perspective of a child, whose sadness is as insurmountable as a tiny handmade tower behind a locked door, and yet also filtered through the colorful lenses of an unbridled imagination. Documentary-style interviews filmed in a smaller aspect ratio abruptly interrupt Georgie’s conversation with Ali about the spiders in her house: in these fantasies, the spiders make fun of Georgie’s loneliness, and their words are captured in speech bubbles befitting of graphic novels. What Georgie is unable to put to words, Regan does so through visually striking means that imbue a child’s incommunicable grief with both brutal honesty and innocent wonder.

While Regan charmingly revises the melancholic tone associated with the kitchen-sink genre, these creative attempts come at the cost of the film’s thematic complexity, which shows in the under-baked relationship between Georgia and Jason, and the superficial critiques of Britain’s welfare services. In addition to depicting Georgie’s grief, the documentary-style interviews also feature weary (and cartoonish) social workers who gloss over the ridiculous name of Georgie’s uncle and her unusual circumstances. However, when the gravity of state negligence is conveyed through what is meant to be a lighthearted aberration in technical style, it also crudely undercuts the film’s desire to criticize these institutions.

Jason’s failure to show up for Georgie in all the years of her life is also skimmed over as quickly as the film’s half-cooked critique of the country’s welfare system. It’s to Dickinson and Campbell’s credit that their electrifying chemistry transforms Georgia and Jason’s relationship into something sweet and gentle to behold. This is not to say that Scrapper is completely devoid of depth when it comes to characterization, but it is unusually restrained when addressing the deep-seated cracks present in Georgia and Jason’s relationship. Every conflict is purely expository — Georgia often tells Jason that he abandoned her — but the film refuses to properly explicate Jason’s absence in her life, or even give Jason the chance to really seek amends. In turn, the reunion between Georgia and Jason feels unearned. In carefully protecting Scrapper from delving into the purported miserabilism of British working-class dramas, Regan sacrifices a layered portrayal of state neglect, paternal abandonment, and child grief. While a boisterous portrayal of working-class joy, it’s still a shame that the kitsch aesthetics of Scrapper ultimately sacrifice the potential for richer interpersonal study.

DIRECTOR: Charlotte Regan; CAST: Lola Campbell, Harris Dickinson, Alin Uzun; DISTIRBUTOR: Kino Lorber; IN THEATERS: August 25; RUNTIME: 1 hr. 24 min.

Comments are closed.