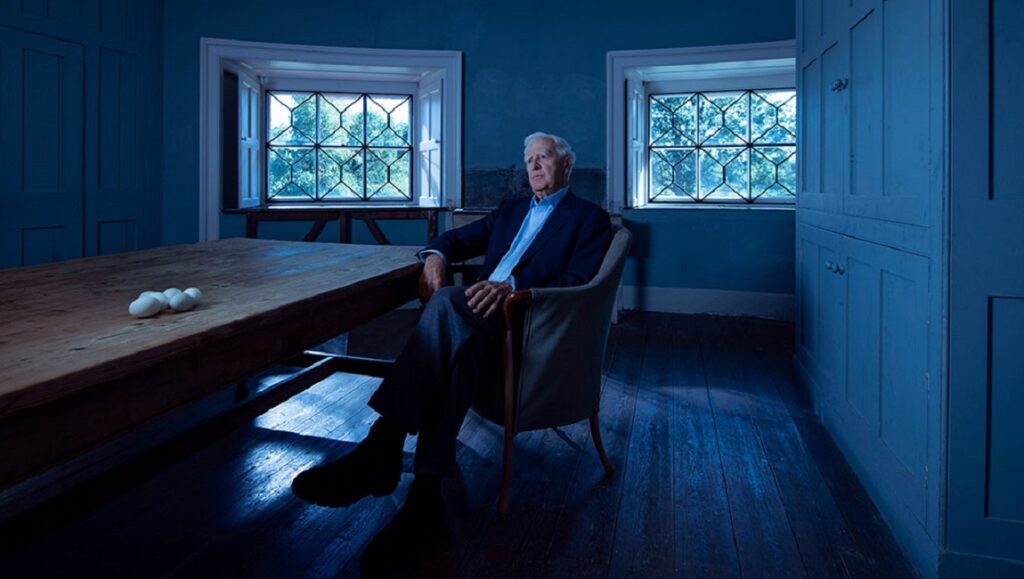

The main question asked in Errol Morris’ newest film — a presentation of late author John le Carré’s final interview — is not posed by the documentarian and interviewer, but spoken by the subject: “Who are you?” A former British spy whose experience with interrogation goes beyond decades of interviews given as a novelist, le Carré, whose real name was David Cornwell, clearly wants inside his interviewer’s head to get a better sense of his specific goals with this project; he’s seen Morris’ films, he says, and finds that the director is sometimes a “god,” sometimes a “spectral figure,” and other times something else entirely. The Morris of this film does not adopt a god-like guise — which is to say, he does not construct his own narrative out of his subject’s words — but neither is he content to merely fill the role of the interviewer. Morris largely gives The Pigeon Tunnel over to le Carre, allowing his legions of fans 90 more minutes with the deceased master, but the documentarian does structure his film into neatly and thematically divided thirds. Morris also pairs le Carre’s words with both his typical reenactments as well as clips from adaptations of le Carre novels (mostly the BBC stuff, but there’s room for The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and Lumet’s The Deadly Affair, too).

The Pigeon Tunnel begins with le Carre’s beginnings — or rather, Cornwell’s — and with it an explanation of this film’s title — which is taken from the author’s autobiography. “The Pigeon Tunnel” was, at one point or another, a working title for each of le Carre’s novels: the phrase references a memory of the pigeon hunting trips Cornwell’s father would often take, and which would end when the birds would travel down a long funnel and emerge on the other end to be shot out of the sky. If the relation of that story to the content of le Carre’s novels needs explaining, Morris cues a clip from the ending of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold — of Leamas and Nan (Liz in the novel) running for the Berlin wall under threat of gunfire. Le Carre’s spies are set-up, duped, constantly put in danger by powers that move in shadows above their pay grade and who, during the Cold War especially, gladly employed former Nazis to fight shallow ideological conflicts while burning their own men. Morris links this tendency not only to Cornwell’s time in the secret service, but to a series of betrayals in his childhood, as the son of a conman and an absent mother who could not go on living with his deceptive father.

Moving on from this exploration of Cornwell’s childhood, The Pigeon Tunnel takes on his years in spycraft, and then his work as a novelist. The spectre of Kim Philby’s betrayal of Britain, and the betrayals committed by Cornwell in the line of his own duty, form a throughline here. But this section is also perhaps the least novel in the film; the insights into le Carre’s work that Morris offers will all be familiar to anyone who’s read even the foreword to his republished editions. Le Carre’s work is disillusioned and angry with the espionage business, a refreshing counterpoint to the heroic illusions of James Bond. But the author has always cautioned against praise that he’s received when it’s framed around the idea that his more bleak tone makes the work more “realistic.” If he has a regret about his publishing work, it’s that he sometimes constructed a fantasy in which the secret services are confident puppet masters instead of the reality of an espionage apparatus in shambles, where everyone is acting blindly, or on bad, disorganized information — his MI-6 is called “the Circus” for a reason.

The Pigeon Tunnel’s final half hour jumps back to its subject’s personal life to offer a more in-depth look at le Carre’s relationship with his father, conman Ronnie Cornwell, who was incarcerated for portions of his son’s childhood and whose relationship with le Carre only grew more fraught late in life. What’s here is a psychological portrait of both an author and a spy, an investigation into the root causes for the impulse between both of le Carre’s professions. It’s a compelling narrative, to be sure, but also one that eventually seems in search of a point. Pointedly, there’s no moment where le Carre breaks down in tears or reaches a new realization. And while it’s great that the film is able to avoid such easy dramatics, it also shows Morris butting up against the limits of psychology. Le Carre is an odd subject for the director — not a profoundly evil man like Robert McNamara, Donald Rumsfeld, or Steve Bannon (who can all, Morris proved, be given enough rope with which to hang themselves), nor someone with a strange, compelling story, like the subjects of Tabloid or Gates of Heaven. Instead, this is a man who was part of the Cold War machine and whose work, disillusioned and even-handed as it may be, proceeds from a set of liberal ideological assumptions. Morris, with all his psychoanalytical investigation divested of ideology, can muster few concrete answers about what shaped the most literary of spy novelists. Le Carre is quick to compare himself to the metaphorical room harboring all the secrets of the state: access only reveals the room to be empty. Taken as a final interview with one of the great writers of the second half of the 20th Century, The Pigeon Tunnel is a joy — an engaging time spent with a lively, entertaining mind. As a new documentary from one of the masters of the form, however, it appears minor; a film lacking in purpose and new insight.

DIRECTOR: Errol Morris; CAST: Jake Dove, Charlotte Hamblin, Garry Cooper; DISTRIBUTOR: Apple TV+; STREAMING: October 20; RUNTIME: 1 hr. 32 min.

Originally published as part of TIFF 2023 — Dispatch 2.

Comments are closed.