Strange Way of Life

A 32-minute queer cowboy melodrama paid for by Yves Saint Laurent, Strange Way of Life is Pedro Almodóvar’s second English-language short and, like The Human Voice before it, feels so listless and underdeveloped that it makes you question why it was ever made in the first place. Is this just Almodóvar’s way to test his abilities as an English-language auteur? Or is he finally making up for the fact that he turned down Brokeback Mountain? Maybe it’s just an advertisement for the fashion label and YSL creative director Anthony Vacarello’s outfits; or, perhaps, it’s a sincere attempt at a serious piece of cinema? Or could it even be some deliberately hokey, ultra-ironic sort of joke? Whatever it is, Strange Way of Life barely feels like a movie.

The hurried-through plot goes something like this: Silva (an incredibly wooden Pedro Pascal) rides into a generic Western town looking for his ex-lover Jake (an incredibly hammy yet compelling Ethan Hawke). Silva’s son killed Jake’s daughter-in-law and now Silva is there to ask for Jake to spare his child in the name of their long-past love for each other. When Jake refuses, however, the drama of the past bubbles to the surface, manifesting itself in a violent denouement that unfolds so briskly that it’s barely believable. But first, they’ve got to do a little bit of gratuitous fucking — they haven’t seen each other for 25 years, and, no matter how tame the whole enterprise is, it’s still an Almodóvar film and he does know how to give the people what they want.

The film’s heart lies in its melodrama and Silva’s attempt to evoke the spark of their repressed romance. Therein also lies the major problem of the film: Hawke and Pascal have such little chemistry that it’s hard to believe they even have any present connection, let alone a loaded past one. It doesn’t help that their campy performance styles feel cribbed from two different movies and that it’s all shot in that overly bright and clean, fluorescent-heavy style of the director’s 21st-century work (almost all of which was lensed by José Luis Alcaine). Strange Way of Life has that static, overly-polished feel which smoothes away any of the expressive transgressive energy that might still remain in favor of a distanced, all-too-clean look. It also, coincidentally, sort of looks like a fashion commercial.

20 years ago, it might have been captivating to watch two very hetero A-listers fawn over and fondle each other, but today, in a post-Brokeback world where it’s become almost a career move — Benedict Cumberbatch, Rachel Sennott, Timothee Chalamet, etc. — to make that the sole selling factor of the film is almost regressive. Yet by the time the credits abruptly roll around mid-scene, almost like some meta/Godardian joke on film form, it’s hard to find anything else really on in the film, both on its surface and in its vague motions toward depth, besides the simple appeal of watching the sex. In a year where the concept of the auteurist short has really emerged in full-force, seemingly out of nowhere — see also works from Yorgos Lanthimos, Wes Anderson, Pedro Costa, and Lucrecia Martel — and seems to hold the significant promise of rejiggering film standards, it’s frustrating to find something so beguiling in its very existence. But maybe this is overthinking it; Strange Way of Life probably really is just a commercial for YSL. — JOSHUA BOGATIN

in water

As the star of Hong Sang-soo has improbably grown, the traditional (and often erroneous) stereotypes lobbed against his films have stayed stuck in the mud. None of these are fair, strictly speaking, impressions largely drawn from loglines and ignoring the often wild differentiations that arise between his films, especially those in… [Previously Published Full Review] — RYAN SWEN

La Chimera

Alice Rohrwacher’s cinema occupies a unique place in the festival landscape, part pleasingly familiar and part bracingly daring, especially in the context of her relatively meteoric rise. After her debut Corpo Celeste played in the Director’s Fortnight sidebar at Cannes 2011, her sophomore The Wonders won the Grand Prix at Cannes 2014, Happy as Lazzaro won general acclaim in 2018 (also at Cannes) and still stands as one of the most unexpected Netflix acquisitions ever), and her short film Le Pupille from last year somehow even garnered her an Oscar nomination. This has all come as her style and concerns have remained consistent, a melding of a general Italian neorealist heritage with a disarmingly casual approach to magical realism, all caught on rough-hewn textured images as shot by Hélène Louvart.

As Rohrwacher’s body of work has grown, her films have increasingly taken on a mythic dimension, signaled sharply by the mid-film time jump of Happy as Lazzaro, and her newest feature, La Chimera, moves several steps forward. Set sometime in the 1980s, the film follows Arthur (Josh O’Connor), a moody Englishman who has just finished a prison sentence in central Italy as he returns to the rural town where two groups vie for his attention: the denizens of the decaying estate where the mother (Isabella Rossellini) of his lost love Beniamina holds court, and the members of his gang of tombaroli (tomb raiders). He is the focal point of this latter group, using a seemingly innate connection to the earth and ad hoc dowsing rods to sense the locations of Etruscan graves, whose underground passageways and chambers are as much a promise of profit and liberation to Arthur’s brethren as they are an externalization of his inchoate desire to be reunited with his lover.

La Chimera is powered by such cycles of excavation and potential rebirth, during which Rohrwacher’s approach constantly shifts, jumping between three shooting formats and corresponding aspect ratios — 1.66:1 super 16mm, the primary medium; 1.33:1 16mm, used for brief shots that may be flashbacks or may be dreams; and 1.85:1 35mm, interspersed seemingly at random — and throwing in direct address and scenes of sped-up motion that resemble silent comedy. The effect is one of instability, where everything about Arthur’s situation feels tenuous, most of all his mercurial nature and wavering feelings about his profession, exacerbated by a potential new love in the suggestively-named Italia (Carol Duarte). O’Connor anchors this all with a marvelously beleaguered demeanor, using his relatively towering stature and rumpled suits with a forcefulness entirely different from the sanguine lead in Happy as Lazzaro.

The beauty of La Chimera lies in its grace notes, its unexpected invocations and subterranean motifs. Though nearly all involved suffer a tangible, realistic downturn in their fortunes, with Rohrwacher’s sister Alba providing a cameo as a multilingual antiques fence that stands in for all the wider economic and cultural forces chipping away at these hapless paisans, it is romance and myth that govern the day, in loaded images such as frescoes slowly oxidizing when the underground seal is broken, a swirling flock of birds seemingly flying at random, and a red thread that invokes the myth of Ariadne and the labyrinth. Arthur’s quest, in the end, relies equally on the machinations of man and seemingly divine intervention, and Rohrwacher’s film is expansive and wondrous enough to incorporate both with an overwhelming grace. — RYAN SWEN

The Sweet East

An easy bit of advice to give to any filmmaker who tries, whether with journalistic integrity or well-meaning folksy soapboxery, to make a film about our contemporary political moment: don’t. It’s easy enough advice to follow, and it frees the advice-ee from the label of cringe that can only come from the same culture that had initially… [Previously Published Full Review] — ZACH LEWIS

Trailer of a Film That Will Never Exist

We’ve just passed the one-year anniversary of Jean-Luc Godard’s death via assisted suicide. Those closest to him suggested his advanced age and ailing health led to the decision, while others claim he was simply exhausted by life. There’s a thousand eulogies and obituaries out there, a testament to Godard’s towering stature and importance to the art form, although there’s no real way to make sense of his immense body of work in its totality — Godard was too opaque, cryptic, willfully gnomic for such easy summations; the existence of the new Trailer For a Film That Will Never Exist: Phony Wars presents, then, a confounding (if extremely beautiful) object — a fragmented preview of a larger work that will never come to fruition, a suicide note, a communique from beyond the grave.

Common for Godard’s work, the English-language trade press has little to no use for this sort of film, but Craig Keller has provided the great service of translating and publishing Marco Uzal’s writing on the film after its Cannes premiere. Uzal writes, “for Godard… every movie is a construction site, and every film construction site is itself a film.” Uzal cites as precedent Godard’s penchant for releasing essayistic “scenario” films, i.e. Scenario of Sauve qui peut (la vie), Scenario du film Passion, and Small Notes Regarding the Film Je vous salue, Marie; Orson Welles had a similar penchant, and of course as Jonathan Rosenbaum has observed, “Godard was hated as much as Welles by the commodifiers who could find no way of commodifying his art, of predicting and thereby marketing his next moves.”

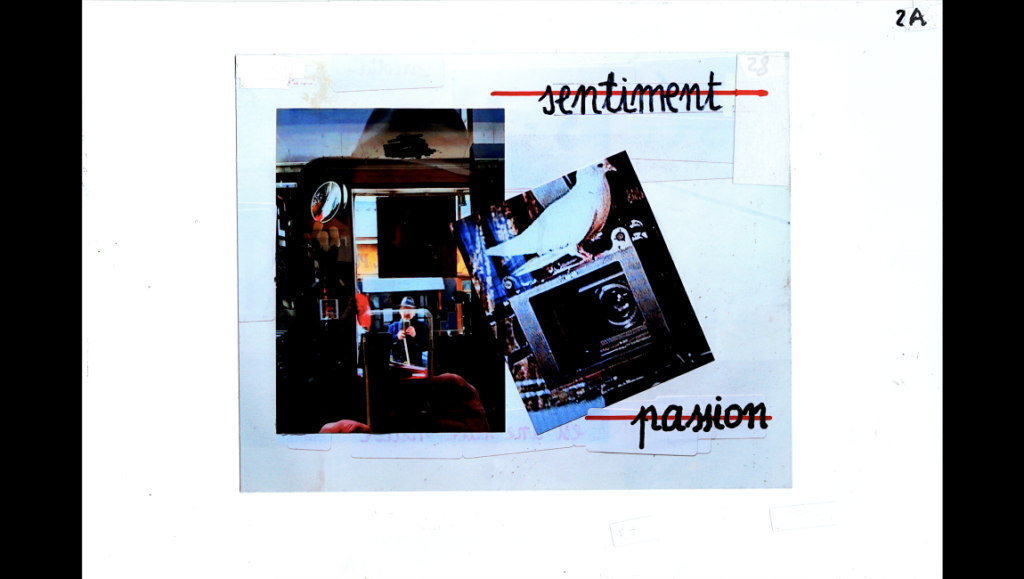

So the film is essayistic, yes, but maybe more in the way of a scrapbook, or a sketch. Multiple collaged images arrive with handwritten notes, scribbles, underlined passages, and crossed-out words, splotches of ink and paint. One recalls Maurice Serullaz’s quote, “Drawing is the artist’s most direct and spontaneous expression, a species of writing — a study of even the swiftest sketch discloses the mind and nature of its author.” Godard was of course a writer, too, a fine one, and Phony Wars often feels like a prolonged utterance, a run-on sentence that shades in some modes of thought while never settling on one or the other. So how to make sense of this unclassifiable object, equal parts film, video, sound, painting, writing?

The film begins in silence, as still frames flit across the screen. There is text, some more legible than others, and Godard indulges a kind of joke, the subtitles for which translate as “It’s hard to find a black cat in a dark room, especially if it’s not there.” Another image reads “Notre Guerre” (Our War). Eventually, somber chamber music swells on the soundtrack, then a woman’s voice begins speaking. More hand-written notes, like graffitied slogans: “the camera is just an old quantum epidiascope” (an optical projector capable of giving images of both opaque and transparent objects) followed by “the news from Spain was bad.” There are now reproductions of impressionist paintings, xeroxed copies of images, clippings from magazines and newspapers, Polaroids, smears of paint a la Franz Kline’s black line works, blown-out frames with the typography from Histoire(s) du cinema.

Finally, we hear his own voice, raspy and labored, but quite beautiful in its way, still somehow stentorian even as it quavers. Godard begins describing his admiration for Belgian writer Charles Plisnier, and how he had hoped to adapt his novel False Passports into a film titled Carlotta. Godard says he was interested in the way that Plisnier “drew” portraits of certain activists he knew in the 1920s, presumably fellow Trotskyists who would all eventually be expelled from the Soviet Union. Plisnier would eventually abandon Communism for Catholicism while maintaining his allegiance to Marxism, a convoluted sort of melange that would presumably appeal to the political vagabond Godard. The director observes, “he [Plisnier] was more like a painter than a writer, he painted portraits of people’s faces or how they looked.” Godard wonders aloud if he could go back and make a film knowing what he knows now, and if he could make it in the way of Melville’s Le Silence de la mer.

Kent Jones once wrote an essay titled “Can Movies Think?” That’s a hard question to answer, but certainly, Godard’s films are exhibits of one artist’s thinking, volatile and out loud, thinking rendered as a piece of action painting as much as a film. Godard long associated his filmmaking with the 20th Century, finding them intrinsically linked, and often declared the “death of cinema” as the world barreled toward fresh barbarism while refusing to reckon with past atrocities. But as Patrice Rollet has observed, one of the “possible types of cinematic death” belonged to both Serge Daney and Godard, for whom “in its disappearance, cinema appears.” “I wonder sometimes,” Daney writes, “if it were necessary for cinema to disappear to move from a state of limbo to center stage, from fog to light…” Godard liked to say that “cinema taught him how to live,” so perhaps it is fitting that even in death, he is still using cinema to try to make audiences see anew. — DANIEL GORMAN

Music

Read a review of any of Angela Schanelec’s feature films and you’re bound to encounter adjectives like “elliptical,” “confounding,” and “obscure.” It’s true — the German filmmaker has a peculiar approach to storytelling, favoring all manner of narrative obfuscation while honing in on movements, gestures, and that… [Previously Published Full Review] — DANIEL GORMAN

The Settlers

A lush, elemental reckoning unfurls across the relatively condensed runtime of Felipe Gálvez Haberle’s debut, The Settlers, even if few of its proceedings strictly qualify as terse. In fact, the film’s tersest narrative developments are matched by a formal languor which, enveloping the mountainous landscapes of Patagonia alongside its portraits of fin de siècle colonialism, conjures the phantasmic imprints of a history hastily realized and therefore not quite resolved. This history has a name and face: the Tierra del Fuego gold rush from 1883 to 1906, drawing Chileans, Argentinians, and Europeans alike to the southernmost tip of mainland South America in pursuit of untold riches, also precipitated the displacement and genocide of its indigenous tribes, notably the Selk’nam people. Whether due to purely economic calculation or to scientific (dis)interest — many of those slain had their skulls shipped to Europe for anthropological research and display — or simply out of wanton contempt, the colonial quest for profit heralded years of destruction whose reverberations continue to haunt the region’s illustrious cultural legacy.

In The Settlers, however, what’s at stake isn’t gold, but sheep: garish intertitles note the comparable worth of livestock, or “white gold,” to the colonial enterprise. The national drive toward modernization coincides happily with the individual search for wealth, and one José Menéndez (Alfredo Castro) pursues the expansion of his sheep business with ruthless resolve, entrusting the search for safe passage — to transport his herds across Patagonia — to a handful of mercenaries. They comprise Alexander MacLennan (Mark Stanley), donning the uniform and prestige of the British army; Bill (Benjamin Westfall), Texan sharpshooter and archetype; and the mestizo Segundo (Camilo Arancibia), whose reserved demeanor stands in sharp contrast to the bluster of his companions — effectively his superiors. Traversing cliffs, ravines, and the odd smoke-stack of primitive civilization, Menéndez’s crew journey to the ends of the world and, by extension, those of the imagination. Their encounters with the Selk’nam, as well as other prospective settlers, gradually reveal a universe fundamentally bereft of certainty except in nature’s stark moral indifference: where the elemental terrain meets the mercurial will, violence almost always ensues.

Ironic, then, is the film’s title, which ostensibly substitutes the more explicit denotation of “colonizers” for an outwardly benign description of terraforming and settling on land implicitly parceled out for this specific purpose. But settling just as easily recalls its negative, often applied to the foreign and uncanny: in The Settlers, Patagonia unsettles precisely because no such injunction towards exploitation, whether God-given or legally decreed, is truly commensurate with the moral compasses of those caught up in its compelling fever. Segundo, whom we first see tending to livestock, is of ambiguous yet clearly different origin from the trigger-happy Alexander, and his complicity (first in taking up the mission at the latter’s request, then in directly perpetuating some of its violence himself) painfully comes to light in Gálvez’s antipodal Western. Playing with some of its most vaunted conventions — the men search, strip, and shoot their way to infamy — yet retaining a disquieting clarity amidst the delirium, The Settlers keenly dismantles the romanticism that percolates through most contemporary renditions of expansionist madness. In this regard, its acuity and reflexivity far surpass that of Hlynur Pálmason’s acclaimed but emotionally inert Godland, a diorama ravishing in substance but emptied of all formal inventiveness.

This inventiveness may be mistaken as the trappings of directorial inexperience, for Gálvez’s treatment of the settlers, especially before the onset of terrible savagery, vacillates somewhat arbitrarily at first. From antics of ribald masculinity, upon meeting their Argentinian counterparts, to downright sadism by the misty dawn of a sleepy indigenous dwelling, the film’s tonal dissonance traces, rather, a continuity between the markers of humanity and the viscera of untempered bloodlust; here, Gálvez defiantly reconfigures historical memory to juxtapose civilization with its inhuman tendencies, tacitly undermining the settlers’ claim to moral justification. Of course, this is nothing new in a time where past exploits have been routinely decried, and one could certainly situate The Settlers amid a tradition of post-colonial, post-modern cinema, the likes of which include works by Lucretia Martel, Lisandro Alonso, and Pedro Costa. But Gálvez’s ambitions are also more modest and more concrete; his film, bearing a quote from the humanist Thomas More, examines how the brutal logic of territorial and capital gain frequently overshadows any resurrection of humanist idealism. More, in his Utopia, wrote of sheep “now become so great devourers and so wild, that they eat up and swallow down the very men themselves.” What The Settlers does tremendously well is to revive this notion in a twofold way: first by underlining this materialist logic, and then by demonstrating how Patagonia’s colonial legacy, unlike the aspirations of many a prospector, is something that can never really be settled. — MORRIS YANG

The Zone of Interest

The issue at the heart of Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest is one of the oldest in the cinema: how does one represent the unrepresentable? Loosely adapted from Martin Amis’ novel of the same name, and set in 1942, the film is centered around the Höss household: a German family who live in… [Previously Published Full Review] — LAWRENCE GARCIA

Kidnapped

Many critics’ wrap-ups from Cannes this year included dismissive language directed at Ken Loach’s new film competition film, The Old Oak. As is often the case with late Loach, the consensus has been that the director’s heart (and politics) may be in the right place, but that he sacrifices nuance in the name of agit-prop. Well, the same… [Previously Published Full Review] — MICHAEL SICINSKI

Close Your Eyes

Víctor Erice’s Close Your Eyes opens to a beautiful autumnal scene of the French countryside in 1947: an old fictional mansion (called “Triste le Roy”) is peacefully visible in the background, surrounded by immense gardens where, in a corner, the bust of a two-faced Janus, with a face of a young guy looking back at what once was and an older bearded man looking toward what’s yet to come, is singled out. In this scene, we find a private eye named Monsieur Franch meeting with Monsieur Lèvi, a wealthy and ill old man whom we understand intends to hire Franch to find his missing daughter in Shanghai. But it’s right after this roughly 15-minute, one-on-one conversation between the duo, when the detective accepts his mission and steps out of the mansion, that we realize via voiceover that what we’re watching is merely a film-within-a-film (titled The Farewell Gaze) and Franch a character played by a Julio Arenas (José Coronado), a famous Spanish actor who disappeared in 1990 with nary a trace and plenty of speculation.

We’re then thrown into 2012 Madrid, where Miguel Garay (Manolo Solo), the director of that unfinished film and Julio’s longtime friend, is about to attend a TV program (Unsolved Cases) which tries to bring the latter’s enigmatic case into the spotlight again after 22 years. This occasion eventually leads Miguel down a labyrinth of memories and encounters, in which he tries his best to figure out what actually happened to Julio. Is he really dead? Was he involved in a fatal affair concerning the authorities, as one conspiracy theory journalist claims? Or did he merely trade his stardom for precious anonymity? One thing is certain: while narratively, the idea of finding Julio presents a parallel (or even subsidiary) driving force for the film to play as a slow burn thriller, we can still readily expect that Close Your Eyes, in Erice’s hands, will gradually move from the investigation of a mystery to broader, introspective investigation. Erice’s virtuosity in poeticizing genre — 1973’s The Spirit of the Beehive is, to this day, one of the greatest examples of amalgamating horror tropes within European arthouse aesthetics — as well as his subtle and patient storytelling results in a magnificent tale of self-discovery, shaping itself as a detailed reflection on life and death, love and friendship, and the philosophical quagmires of time, memory, oblivion, and remembrance.

Mainly structured as a series of lengthy one-on-one conversations between Miguel and other characters, which usually take place in various interiors in order to emphasize the sense of privacy and intimacy, Close Your Eyes treats mise-en-scène in a way that allows the natural flow of the actors’ rhetorical abilities to play a crucial role in enhancing the whole of the film’s beguiling atmosphere. Utilizing plenty of various materials, from books to photographs, archival footage to movie posters, and even a couple of songs that assist Miguel’s (personal) investigations along the way, Erice’s unique visual regimen and tranquil narrative distributions embrace a very specific archeology of the past; politics, lost loves, and, perhaps most importantly, film history itself — it’s indeed not accidental that Miguel once published a novel whose title (Ruins) bears an eloquent echo. This archeology is also expertly articulated through Erice’s baroque chiaroscuros — the different shades of light and dark working in tandem with the film’s essential concepts of appearance, disappearance, visibility, and invisibility — and elegant compositions (specifically, his random frame-in-frames).

Whether through the movie posters of Charlie Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux and Nicholas Ray’s They Live by Night or through direct homage to Howard Hawk’s Rio Bravo — in one of the rare scenes that features more than two characters in conversation, Miguel and some friends sing “My Rifle, Pony & Me” — Close Your Eyes’ undeniably cinephilic weight and scope are a perfect fit for Erice — who himself arguably disappeared, or at least became somewhat of a recluse. This film marks the director’s first feature in 31 years, after the release of his 1992 docudrama Dream of Light, and is an excellent vehicle through which to re-examine questions of life’s meaning with the help of his appreciation of film. But despite all of Erice’s obvious allusions to the medium, Close Your Eyes is still inherently a meta-film that must be viewed simultaneously as a fraction and overlap of fact and myth, truth and fiction, the real and the image; the subtler connotations between his work and that of Michelangelo Antonioni’s in L’Avventura and Blow-Up (with certain amounts of Hitchcockian tendencies) may be of interest to viewers as well. In the film’s penultimate scene, before Miguel finally hosts his climatic, emotionally moving private film screening — which can also be seen to mirror the unforgettable scene Erice conjures in The Spirit of the Beehive where children watch James Whale’s 1931 Frankenstein — Max (Mario Pardo), an old friend who is a projectionist and archivist, skeptically but kindly asserts, “You think a movie can bring about a miracle? Give me a break! Miracles haven’t existed in movies since Dreyer died.” It’s a fitting statement to engage with the work Erice delivers in Close Your Eyes: the director allows us to keep our faith in the beauty, mystery, and magic of films as a constant act of remembrance in the face of oblivion. It offers up a very particular immortality in the face of death, such that, in a Janus-like manner, we can turn our gaze toward both the past and the future of cinema. — AYEEN FOROOTAN

Last Summer

As Catherine Breillat’s first film in a decade, Last Summer scans initially as an altogether more mannered affair for the director. Known for her sexually frank inquiries into desire, taboo, and transgression, Breillat’s latest drops us into the upper-crust world of Parisian… [Previously Published Full Review] — LUKE GORHAM

We Don’t Talk Like We Used To

We Don’t Talk Like We Used To, the title of Joshua Gen Solondz’s latest film, has a few potential meanings to account for. The first is an intimate shorthand, referencing a confidentiality between two people that forms the daily thread of a relationship. To speak these words can herald either a reunion or a final disbanding. The other meaning might take “we” in the universal sense, and “talk” to stand in for communication writ large. Meaning, this proposition suggests, is not transmitted how it once was. The old lines have been cut, and reunion becomes a little more complicated.

Cinematic language was developed in response to a world scarcely recognizable from the one in which we live today. Better than most, Solondz understands its inadequacies to the demands of the present moment. The filmmaker’s flicker-stutter strategy rushes the optical nerve before his images have a chance to be corralled by conscious understanding. Solondz meshes textures, rarely lingering in one format long before it’s corrupted by a strobing overlay. Our access to a stable bottom layer is perpetually thwarted. Often, this is accomplished with a stratum of clear film leader that’s been scratched, painted, and seemingly dragged through the dirt. Otherwise, collages of saturated video footage intervene, deconstructing the discreet image and veering constantly from figuration to glitch art abstraction. It’s jarring when the obstructions fall away, and a steady stream of 16mm frames proceed unmolested for a moment, but Solondz’s decision to leave the gate hairs in, persistent Morgellons fibers crowding the edges, should be understood as just that.

Smoke billows into many of Solondz’s images, and intertitles penned in dripping death metal scrawl attest to an apocalyptic climate. “It feels like you’re on fire, you say,” one asks. Another feels less cryptic: “The air is thick with poison.” The film is flush with masks, largely balaclavas with and without eye and mouth cutouts, and the centerpiece prominently features an N-95. In an arresting sequence, Solondz alternates split-second moments of a masked figure donning and removing the PPE. The cyclical movement — stretching over six minutes — is protracted to the point of hysterics, but it hews closer to the actual memory of living through Covid than anything made since. Inside one day, outside the next, masks are only for doctors, masks are for everyone, cases up, cases down. The fingers, adjusting the elastic straps in both ends of the movement, seem to twitch and squirm in a dizzying cycle. It’s a trance only broken when Solondz cuts to a scene of himself tying a plastic bag around his head.

This transition doesn’t simply echo the oft-heard complaint that masks are suffocating. Masks have been a fixation for Solondz since long before the pandemic — 2016’s Luna e Santur, for instance, found the filmmaker shooting two figures in bedsheet ghost costumes, and again working with visual obstruction, forcing the viewer to squint through a migraine-inducing flicker to perceive his images. But We Don’t Talk Like We Used To proceeds with the manic energy of one recognizing in the world what was previously known via instinct. If it’s a redoubling of his strategy, rather than a reinvention, it raises the question of post-pandemic art to the level of urgency. Covid didn’t reveal anything especially novel about society, but it did make pre-existing contradictions impossible to ignore. Solondz returns to the same drawn-out approach for his finale. Two masked figures approach one another as they simultaneously seem to pulse and flicker apart. Their final embrace is equal parts emotional and disconcerting. It reminds of an image from earlier in the film, of an empty pair of pants attached to some sneakers, with thick smoke pouring out of them. There might be a reunion, but things will never be the same. We don’t talk like we used to, because we’re not what we used to be. — DYLAN ADAMSON

The Delinquents

Blanket declarations about three-hour-plus runtimes always seem curious when filmmakers employ said length for wildly different purposes. Though the sweeping epic may be the most classic Hollywood implementation, the space can be used to house labyrinthine plots, emphasize repetition, or facilitate other… [Previously Published Full Review.] — JESSE CATHERINE WEBBER

Comments are closed.