The superficial recreations of the Wes Anderson AestheticTM have kickstarted a new metric in art evaluation based on their ease of A.I. appropriation. While A.I. struggles to decipher Margaret Atwood’s syntax from bootlegged copies of her books, its “success” in spawning Wes Anderson content in Star Wars trailers and architectural spaces surely points to Anderson’s failure as an artist, his status on the verge of being relegated to the same trash heap as naïve, pretentious “modern” artists in this codified capitalistic world, with smug smart alecks soon boasting about how their kids could make Wes Anderson films once A.I. is fully mainstreamed.

The kernel of truth in this glib condescension is, of course, that Wes Anderson’s films are instantly recognizable. But even his detractors, a demographic this writer leans toward from time to time, will agree that his aesthetic, at least in his initial films, comes from a position of personal involvement, a means to explore certain themes dear to him rather than a customizable warm palette tailored for audiences who don’t want their films to be too dark. In such a stultifying climate, any critical comment on his films (too twee, cute but cold style, glib, politically stunted, etc.) is only weaponized by the self-proclaimed “A.I. Artists,” leaving us to carefully weigh their criticism.

If the A.I. posts are terrible pastiches of Anderson’s works, his late string of films, at their worst, often end up being pastiches of his earlier films, with their leftover emotions and themes barely holding his narrative conceits together. Anderson is skilful enough to ensure that they don’t fall apart, but his films often end up being… too twee and calculated indeed. Hazy allusions to loss, loneliness, and love don’t seem enough anymore, and what felt fresh in Rushmore — cross-generational connections, discordances between societal expectations and personal wants, alienation in a rapidly transforming world — appears worn out now, especially when he transposes his themes onto politically fraught backdrops. Anderson’s inability to discern anything concrete from his settings, aside from some vague suggestions of encroaching darkness, renders his environments as nothing more than pretty wallpaper; consequently, his characters suffer as well.

His latest feature, Asteroid City, is beset with both these problems, and once again, the film is, again, too twee, as Wes Andersonian whimsy fills the emotional void his characters leave (although nuclear paranoia whimsy is still way better than Oppenheimer’s aggrandizing self-importance). However, he does something interesting by doubling down on his artifice, responding to criticisms of “style over substance” through articulate self-reflexivity. The fiction at the core of Asteroid City is overmined by the fiction behind the making of it, intricately tying the creative process with its result as Anderson seamlessly transitions between the two. It isn’t a surprise that the most poignant sequence comes from the backstage of the televised play staging the main fiction of Asteroid City, where the actor playing one of the protagonists (Jason Schwartzman) casually talks to an actor (Margot Robbie) from another play about a deleted scene in Asteroid City. Ghosts from discarded drafts waft into the hallowed airs of the finished work, the profound insights and petty frustrations weaving themselves equally into it. Art is a welter of contradictions held together by artifice, so fussing over style and substance is rather moot.

The sprawl of Asteroid City, emotionally and politically, lets these interesting ideas slip away from Anderson’s grasp, so the choice of adapting four Roald Dahl short stories provides him with a more intimate setting to concentrate on the metaphysics of artifice and adaptation. In each of them, Anderson immediately calls into question the notion of a “faithful” adaptation by making his narrator(s) address the camera and narrate the sentences near-verbatim from the texts with a deadpan rapidity. As always, the characters are boxed in ornately symmetric frames, though they might be positioned slightly off-kilter. The subtlest of inflexions from all the actors betray their position of objectivity fleetingly, only for them to regain their composure quickly. Sudden frissons of emotion are attenuated by a measured “he said,” and the character-narrators occasionally turn toward their peers in a conversation, only to turn back to the camera with a machine-like precision. The narrator’s near-stoic presence in the foreground appears to be almost at odds with the shifting backgrounds and conveyor belt of players (characters and makeup artists). This deceptively simple tension between foreground and background transforms the literature, rendering it as a cinematic object even if, or rather because, Anderson uses what is considered to be a “literary” or “theatrical” device of narration. These films are about the process of transposition itself, and harping on the faithfulness of adaptations ignores the possibilities inherent to the medium of adaptation.

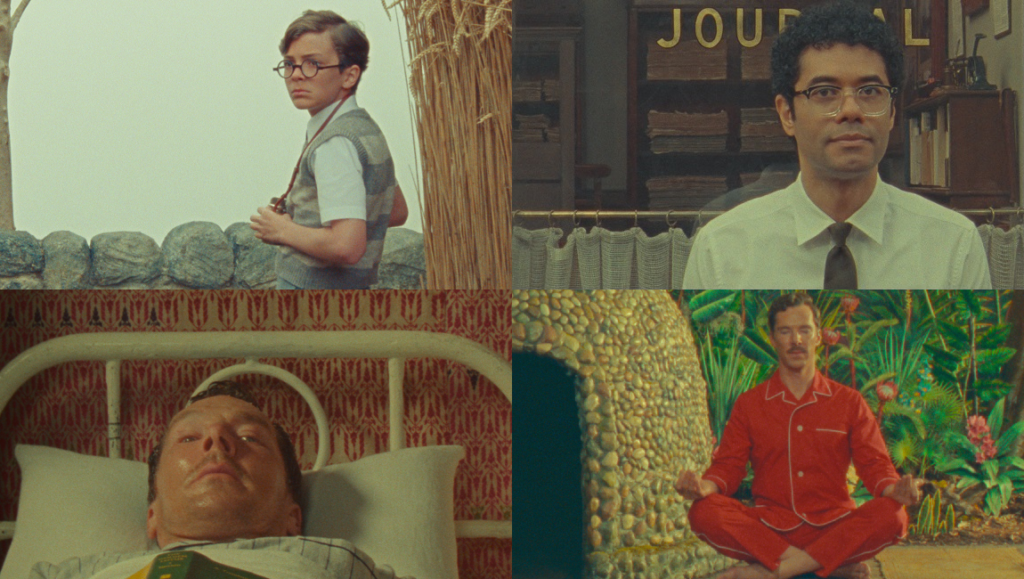

Though all four films similarly involve the theme of transposition, Anderson uses the natural variations in the stories to push these themes in different directions in order to critique our engagement with art. The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, the longest and most acclaimed of the quartet, involves a nested narrative; easy to understand why Anderson was attracted to it. Roald Dahl (Ralph Fiennes) tells the story of a British aristocrat, Henry Sugar (Benedict Cumberbatch), discovering a document written by an Indian doctor (Dev Patel) about Imdad Khan (Ben Kingsley), a man who can “see” without his eyes after learning the skill from a yogi. Dahl’s continent-spanning tale is actualized through shifting sets that are pulled apart or raised to reveal newer sets, with the previous narrator dutifully passing the baton to the next in line. Though the story’s denouement of Henry Sugar discovering the futility of monetary gain is too pat and the redistribution of his wealth reeks of the naïve myth of the benevolent billionaire, Anderson’s handling of Henry Sugar’s narration as a man passing on his knowledge from an enlightened perspective is nothing short of extraordinary. The transformed Henry Sugar regards overt displays of emotion as petty superfluities, and the only semblance of excitement emerges from a wide-eyed Patel shocked at Imdad Khan’s abilities, before he tempers it in favor of “objective” narration.

Henry Sugar was also praised for its commentary on spiritual appropriation, though this seems to be tenuous at best, like the nebulous political commentaries in his other films. The Poison, however, is an upgrade on that aspect, as the “faithful” adaptation of the source story also leads to a directness of address. A racist British landlord (Benedict Cumberbatch), terrified of a krait on his bed, makes his Indian servant (Dev Patel) call for an Indian doctor (Ben Kingsley), only to be later embittered by the fact that an Indian saved his life. The overt racism in the story allows Anderson to subtly explore the class and racial stratifications inherent in colonialist India, and this manifests with a remarkable lucidity absent in his other films. The story is mostly narrated by the Indian servant, and Anderson’s handling of the various spatial planes indicates the rigid demarcation of rooms in the house, with the servant afraid to even imagine himself in his master’s room without the latter’s approval. Even though Patel’s narration is clinically focused, subtle tinges of fear creep into his eyes when the doctor enters his master’s bedroom, and the narration shifts to the bedroom only when the servant is called for by the doctor.

The Poison represents a quantum leap for Anderson in terms of his political filmmaking, which subsequently leads to the deepening of his style. It’s possibly his best work since Rushmore, though one could make a good case for The Ratcatcher as well. A reporter (Richard Ayaode) tells the story of a rat exterminator (Ralph Fiennes) who boasts about his understanding of rat psychology until his trap to kill the rats fails. Casting Ralph Fiennes as both Dahl and the exterminator is a stroke of genius as Anderson, clearly brimming with multiple ideas, also critiques Dahl’s work as a writer. This strain is at its clearest in The Ratcatcher, and its casting shows that the shorts don’t exist in isolation, but are intricately interconnected with each other and must be taken as a part of a broader whole in the vein of anthology films like Le Plaisir (as Richard Brody pointed out). In The Ratcatcher, the exterminator appears to find a kindred spirit in rats, as evinced by Fiennes’ rat-like demeanor: awkwardly broken teeth and gnawing grins. As an oddity, the ratcatcher is a fascinating figure — professionalism in his case is a mirror of perversion. It’s almost immaterial how successful he is at catching rats, as watching him is itself an arresting experience, so much so that Anderson does away with the poison and rat so that he might simply have him enact in pantomime. Despite the plethora of cinematic devices at his disposal, Anderson withholds them here to conjure the powers of imagination. The objectivity of the reporter momentarily gives way to an expressionistic sequence whereby Anderson blackens out the entire background to light up only the faces; the ratcatcher has thrown all objectivity out of the window. Only when the ratcatcher bites the rat — Anderson shows a plastic rat for this scene alone — does the fascination become unbearable, leading him to quickly scamper from the scene. Being an artist, sometimes, is like being a tightrope walker.

All three of these shorts see subjectivity sinuously creeping into the objective narration, but The Swan, the fourth in Anderson’s Roald Dahl anthology, deals with this the most clearly. A tale of horrific brutality, The Swan is narrated by an adult (Rupert Friend) — about a scarring bullying incident when he was a child — in the third person. He only casually reveals that the story is about him in its middle, after which he switches to third-person narration yet again. Anderson constantly undermines Friend’s deadpan narration through make-up artists entering the scene like clockwork to apply blood to the actor playing him as a child (Asa Jennings). Modernism’s famous theme of the constructive nature of memory is enmeshed with questions about the manipulation of narrative through this very device, although it must be said that this is where Anderson’s cleverness minimizes the powerful emotions in the narration — a near-death experience is rendered limply, with Anderson being more interested in questioning the veracity of the incident than the horrors associated with it in itself. It’s all the more puzzling that the most devastating scene in this anthology occurs at the end of The Swan, with the landscapes emptied of characters, leaving behind only Friend’s narration of the brutality, after which the cracking of wood blackens the entire frame and Fiennes completes the story. The impossibility of reimagining trauma and the manipulation of narration are at odds with each other in this film, and perhaps Anderson needed more than its 18-minute runtime to flesh out these themes better.

As a quartet, however, these shorts are a pleasant surprise, opening up different possibilities of cinema broadly and Anderson’s style specifically. Pauline Kael famously described cinema as a bastard art, and true to that dictum, Anderson pinches elements from theater, painting, and literature. But like his commentary on adaptation, cinema is capable of uniquely synthesizing these elements into something different. Gone here is the staleness that infected his recent work, and though he might remain a stubborn stylist, only a stubborn stylist can plumb deeply into the latent possibilities of their style, thereby pushing the art form in newer and bolder directions.

Comments are closed.