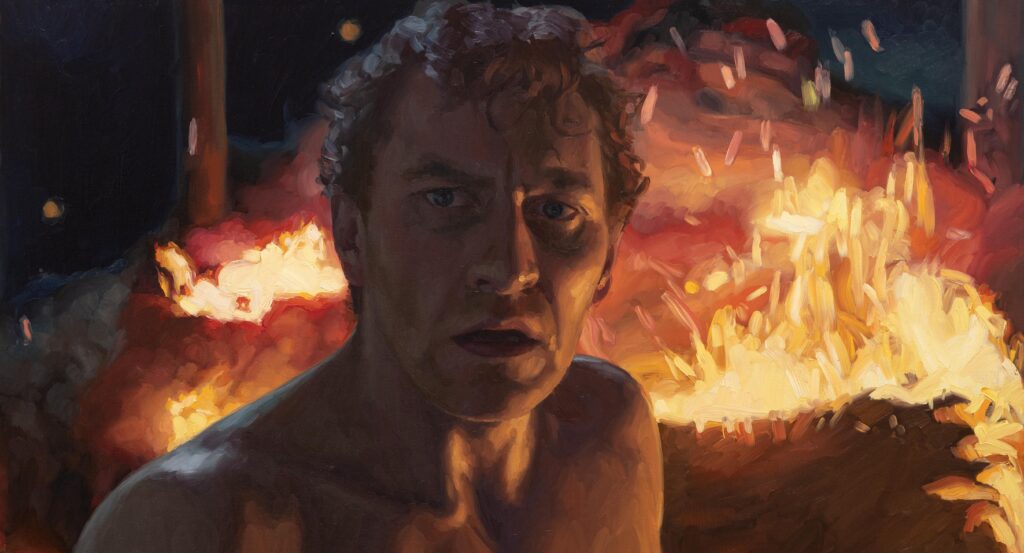

Cinema has undergone two significant, canvas-expanding innovations so far in the 21st century. The first, as ushered in especially by the films of Timur Bekmambetov and Bazelevs Company, came was the advent of screenlife. As with the introduction of sound, color, or 3-D, film art here demonstrated a new mode of presentation. The second innovation came with the paint-animation films of D.K. and Hugh Welchman. The married couple’s first painted feature film, 2017’s Loving Vincent, was a biography about the death of Vincent van Gogh, and each of the film’s 65,000+ frames was hand-painted using an oil painting technique in the artist’s own style. On average, the frames took about 2 ½ hours to paint. For The Peasants, their second paint-animation film and an adaptation of the Nobel Prize-winning Polish novel of the same name, the elaborate and detailed style, as well as the more sophisticated camera movements, made it so that each frame took roughly five hours to complete. As such, only the keyframes were painted, and then supplemented with the work of computer animation artists. The filmmaking process, which here took more than 200,000 hours of work, is, as Hugh Welchman says, “the slowest form of filmmaking anyone’s ever invented.” The labor of artistry pays off. Even if the film doesn’t work for a particular viewer, any fair-minded viewer would be hard-pressed to deny its marvel or spectacle. “They don’t make them like this anymore” is a cliché that doesn’t work with regards toThe Peasants. They never made them like this.

This interview was edited for clarity and concision.

Joshua Polanski: Congrats on the film. I loved it. It’s now in my top four on Letterboxd.

Hugh Welchman: Great. Wonderful. What are the other films?

JP: Wong Kar-Wai’s Chungking Express, Sergei Eisenstein and Grigori Aleksandrov’s October (10 Days that Shook the World), and Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s The Marriage of Maria Braun.

HW: Wow. We’re in great company. Wonderful.

JP: Yeah, just an awesome movie. Good luck at the awards as well.

HW: Thank you.

JP: [So, let’s get started.] Any film takes a long time to finish, especially the way you make your films. What about the novel The Peasants did you feel was compelling enough to spend the better part of a decade on?

HW: Luckily, we managed to do this one in half a decade. The plan was to do it in three years, but the complications of Covid and the Ukrainian war extended our timeline. So it ended up being four years. If you can count the promotion, then it’d be five.

To oil paint a film is an incredible undertaking and not one to be done lightly because it’s the slowest form of filmmaking anyone’s ever invented. And there are easier ways to make films. Pretty much every other way to make a film is easier than this and certainly quicker. It’s [also] a big financial risk to dedicate half a decade of our creative energies and life to one project.

[Władysław] Reymont spent [seven] years writing the novel, his masterpiece novel. And when he won the Nobel Prize, a hundred years ago in 1924, he beat Thomas Mann and Thomas Hardy. They were all much better known internationally. When they awarded him the Nobel Prize, they [said something] very unusual. Normally, a Nobel Prize is for a lifetime of work. They said specifically they were giving this Nobel Prize for The Peasants, for the achievement of The Peasants, because it’s extraordinary.

There are many good things about it, but [I’ll say just a few].

The first thing is that it really covers the human condition. The conflicts, the family conflicts, the issues over property, passionate love affairs, the marriages, the weddings, the funerals, the battles, and the ongoing kind of interaction among the community. All of that is a kind of a microscope on this small community, and [it] deals with all the big issues in life: what it means to be human and [questions of] religion. And I think that’s because he’s very compassionate about his characters. He shows the awful things that they do, sometimes because of their lack of education, sometimes because of their patriarchal or bigoted views, or because of the fact that it’s such a Catholic conservative society. But often, just because they’re human.

The other is his style of writing. He writes like a painting. It’s so painterly and poetic. I was so disappointed when I went to visit Lipce, the village where the book is set. In real life, it’s kind of flat and boring. But in the novel, the descriptions of nature, the changing of the seasons, the weather, are really painterly.

After I read the book, I phoned DK [Welchman] who had got me to read the book but didn’t tell me that she wanted to adapt it into a film because she was worried it was too Polish. As soon as I finished the book, I phoned up DK and I said, “we should make this into a painting animation film.” If you did it in CG animation or live action, you’re going to miss [something from] his poetic prose. You’re going to miss that poetry of his descriptions of the visual world. You still need it to be intensely real, emotional, terrifying, uplifting. So it’s perfect for our technique because you still engage with the performances of the actors, but we can add this layer to the world that makes it slightly different.

The other thing is the way that we experience the 19th-century peasant world is through painting. There are very few black-and-white photos, and there’s no film footage. The painterly [style] was the most important. We didn’t want to do Loving Vincent Two: just find another painter and bring those paintings to life. We wanted to show that oil painting animation has infinite flexibility.

I’d also say, we felt the issues in the book are as starkly relevant today as they were then. Mobbing, canceling… The mobbing, I mean, maybe now takes place in an online environment. Sexual violence, obviously, is still almost exclusively against women too.

JP: Stanislaw Witkiewicz, of the Yount Poland movement, said that he wanted “the heads of both the mighty and the poorest protected by roofs of a common style.” I see a similar equalizing approach in The Peasants: an elegant painting style, informed by impressionism and symbolism, applied to a story about the rural peasant experience. I also think of Jagna’s paper cutouts: a peasant who is an artist. How did the social and class status of 19th-century Lipce inform the look and sound of the film?

HW: The Polish realists that came just before the Young Poland movement, they were all going out into villages, into the countryside, and, in each country, they were using [art] to critique [their] current society and also as a nationalist expression of where they were. They were using their painting to express Polish identity, because, you have to remember, this was in the time of partitions. Poland didn’t exist because it’d been carved up between Russia, Prussia, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. They were aiming to express Polish national sentiment, Polish culture, Polish pride in their work… whether that be highborn or lowborn

[We draw upon that] painting tradition in Poland and also the painting traditions across the whole of Europe. I don’t know if you spotted it, but there’s a direct reference to Jean-François Millet’s “The Gleaners.”

JP: Of the girls in the field?

HW: Yes.

JP: Ah yes. Thank you for that. And what about the film’s sound?

HW: The music is based on traditional Polish folk music. We gave it a contemporary twist, and it also had to be film music because folk music is played all night and over hours. That’s what it’s designed for. It’s like dancing for hours.

We are interested in this Slavic mysticism movement and this tribal music movement across Northern Europe. In [places like] Germany, Scandinavia, and Ireland, you have these bands that have come to prominence in the last sort of 10-15 years, where they’re trying to reimagine or reconnect with the tribal Viking, this peasant period, or our European origins. We were really influenced by this music movement and that’s why we’re working with Laboratorium Piesni, who are part of that movement. They’re often singing in Old Slavic, older kind of Slavic languages [that are] precursors to Polish. That was very important to us. And the dances, same thing. They are based in Polkas, Obereks, but they’ve been adapted for the film.

JP: How do you approach co-directing? Is it divide and conquer or is it more of every decision being made in consultation?

HW: Definitely a divide and conquer. We wrote it together. But the plan was [DK] was going to direct it on her own and I was going to work on other films. There were some issues with my other films because of Covid, and I was on the set and she put me in charge of doing the music and the costumes, the choreography, the dancing. I was doing that while she was directing. Then we had the Covid shutdown and DK was unwell. So, after the shutdown, I had to take over directing for the final two weeks of shooting.

DK is a painter. I could never be as good as her in terms of detailed approval of the paintings or analysis of the painting animation. She obviously has to specialize in that side of it, and then I work on the sound, the music, and the visual effects. We do it together and we’re equally important as writers, [but] she’s a more important director than me.

JP: When I caught the film in Tallinn, Estonia, a representative of the film mentioned something about the breaking of production with the war in Ukraine and that the production team helped some of the filmmakers get to safety. They also mentioned backup power supplies being purchased and sent to Ukraine. What can you tell me about this?

HW: The day after the war broke out, BreakThru Films, which DK, myself, and Sean Bobbitt are the heads of, immediately bought tickets for all of the Ukrainian painters because we knew that there was going to be a rush for tickets. It turned out that only the women could leave because the men were all of military age.

Most of the women took us up on the offer and took the trains and arrived with rucksacks or suitcases. A few of them were like, “Oh no, we think it’s going to be okay.” So they stayed, and then they decided like a week later, “No, we have to leave.” Then it was more complicated for us because there were no train tickets a week [into] the war. They had to hitchhike instead.

It was just carnage, really. We were in constant contact with them. And, Sean, who lives in Warsaw, which is five hours away from the border point, and one of our heads of painting and one of our production managers would drive to the border and pick people up. Some of them had to come out with their children or elderly mothers. Then we had to find them places to live. The local mayor [of Sopot, Poland] helped us very much. They needed a place for their kids to go to school and we had to register them, which the Polish government made quite easy for refugees. We were just helping them with all of that stuff. And yeah, they started working at our studio. We had 13 refugees working at our studio. We got 15 [artists] out, and two people, very upset and traumatized, decided to not work on the film.

[The refugees] became a very important part of the studio. They just had an incredibly positive attitude. Everyone was a bit upset from Covid and the rising prices, [and we were] miserable because people we were expecting to come couldn’t come. So it felt a bit sad and difficult compared to Loving Vincent. And then, these 13 women turn up who are like, “We don’t have bombs being dropped on us… Let’s paint this! Let’s work. Let’s send money back to our families.” They were so positive, which is not what you expect when you’ve got people who’ve had their houses bombed, been separated from their families, and don’t have any possessions. They’re also amazing painters.

There was pretty much 50% unemployment after the war in Ukraine [began]. So [the male painters left behind] had no means of living and were like “[are] you going to reopen the studio?” We’d lost all our money from Ukraine. Financially, it made no sense to reopen the studio, but we felt like it was an important, small thing for us to do as part of efforts to support the Ukraine and the Ukrainian war effort. So, after four months, we reopened it. Once we reopened it, the strategic strikes by Russia on the power infrastructure meant that there [would be] between one and eight hours of power cuts every day. [Some artists were] traveling up to two hours to get to the studio and sometimes they were just sitting by candlelight or by a head torch light reading or watching stuff on their phones because there was no power.

Every month we were just getting enough money to pay the wages and nothing more. We had zero, zero, zero spare money, and we were borrowing money every month to just get enough just to keep the whole thing going. To buy a generator big enough for the studio was $15, 000, and we just didn’t have $15,000. So we ran a Kickstarter campaign and sold Loving Vincent paintings. We raised $20,000, I think, which was enough to buy this big generator in Germany and ship it to Ukraine.

And then finally, 10 months after the war started, we had a fully operational studio and we got 18 more Ukrainian painters working on the film in Kyiv. It became our second-biggest studio. We also had our 13 Ukrainians working in our studio in Poland, so like a quarter of all the painters were Ukrainian, which was great because there’s a huge talent base there. It’s a huge country [whose] art education system actually trains them in realist painting. They’re like gold dust to us because they’re trained in the painting style.

We really wanted to try and do something to help. We did a charity auction of Loving Vincent paintings to raise money to help build daycare centers for Ukrainian refugee families in Poland. Obviously, we couldn’t raise enough to build the centers. It was a much bigger project that we were a small part of. We raised enough money to pay for the counseling for 50 families, in terms of coping with their new life, integrating into their new life in Poland, and coping with what happened to them in Ukraine.

JP: Wow. That’s a lot. It’s fascinating to hear. As you were talking about the refugee women, I was thinking about the scene in The Peasants where the neighboring village is creeping in on the territory of Lipce. Obviously, it’s different. But there is a conflict over land. Was that something on the minds of people as you were painting those scenes?

HW: Well, that’s a class struggle. Because it’s the local squire. The historical context was that after the third uprising, the nobility in Poland were also suffering a lot because they had been part of organizing the uprising. The Russian authorities were clamping down on the nobility, and the nobility had to sell off their assets. They were deeply in debt to money lenders. There were these situations like the situation in the film where the local squire owned the land, but for time immemorial, the peasants had the right to collect the wood and to graze their animals in the wood. So, if he chops this down because he needed the money, he’s going against the agreement with the peasants that’s been in place for a couple hundred years or whatever. This is a big deal for the peasants. They were defending their rights. I think that, in our minds, it’s about them standing up for what’s really theirs.

But I think that was more in Ukraine with the Ukrainian painters. The Serbian painters and the Lithuanian painters were in a different situation, but, you know, it’s their heritage as well. And actually, a [good] proportion of the paintings that were inspirations were painted by Polish painters in lands that are now Western Ukraine. So a lot of the images, a lot of the visual inspirations, were actually in places that are now in Ukraine. And yes, I felt like… there’s a lot of trauma and conflict in our film, and it seemed to be reflected in what was going on around us and in our production. Next time, I’m going to make a film about rainbows.

JP: I was struck by the complexity of the world-building. There’s a Jewish man wearing a kippah in the background. The seminarian character comes and goes with the seasons, and you still have all these little moments where it really feels like this is a town that’s much larger than what we see.

HW: Yeah. Their village is very homogenous. But when we go into the market, [it’s different.] The Jews often owned the inns in Polish villages. They got the licenses to do that. In the village, there’s one Jewish family, which is the innkeeper. But the local town is very cosmopolitan. We have people speaking in German, Russian, Polish, Yiddish. We have like four languages in the soundscape. That’s all represented.

JP: It really feels like you’re viewing an episode of the life of a city that’s been around for a long time, if that makes sense.

HW: Absolutely. It’s a year in the life of this village, and it feels very real. That’s what [Reymont] manages to capture.

Another interviewer asked me what our film references were, and we didn’t really have any. For Loving Vincent, we had lots of film references.

JP: It’s been adapted before. Were any of the other adaptations important for you?

HW: DK didn’t even look at them. There are only two. One was in the 1920s and is lost. Then there was one which was famous in Poland, a six-hour TV series from the 1970s. It was good for me to watch, but it was completely irrelevant for us. I mean, their Jagna was 34 years old. The story doesn’t make sense if you have a 34-year-old actress for me.

JP: Loving Vincent seems to have been an incredibly laborious feature debut. From an outsider’s perspective, it seems like The Peasants was even more intensive. I’m wondering how many more of these sorts of films do you think you have in you? And is it something that you can only make at this stage in your life when you’re both youthful and near the beginning of your filmmaking careers?

HW: Well, I did do some stuff before Loving Vincent. But I don’t think anyone in the world apart from us would ever do this. It’s insane the amount of labor that goes into it. For me, it’s important to do a trilogy. I already did something about independent spirit and artistic spirit. For me, Loving Vincent was more than just a biopic of Van Gogh. It was trying to show the importance of art in our lives and in helping with our mental health. The Peasants is about how we’re all peasants, really. And we haven’t moved on that much in our communities and the way that we treat each other. The Blaze, [my next film,] is about all of us and where we come from. For me, three will be enough.

JP: Are you moving away from animation after this? You both had an animation background before as well, right?

HW: We both have live-action and animation. We’ve done live action, visual effects, and then different styles of animation: CG, 2D, and stop motion. We’ve done all the different types of filmmaking really.

JP: You even made a new kind of filmmaking.

HW: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Actually, at the moment, I’m very interested in miniatures. DK’s looking at more pure live-action. For myself, I’m always interested in something that’s visually providing something different for audiences because everything’s CG animation or digital VFX. Everything. And now, a lot of the narratives are very similar.

The incredible amount of films and TV series coming out all conform to a more narrow visual look than 20 years ago. We got more material, it’s more slickly made, it’s easier to watch because it’s so well made, but we’re lacking variety. You know, we’re losing languages. We’re losing variety in music too. The same thing is happening there. People are putting together formulas that are nice to listen to, but they’re very similar.

I’m interested in making [art] that looks different and is going to challenge people’s expectations and give them a rest. It will challenge their eyeballs, but give them a rest from CG and the digital [look] that is everything now.

JP: That’s why I love both of your feature films.

HW: Thank you. You should check out Peter and the Wolf. My short film that won the Oscar.

JP: I will.

HW: We went for this hyperreal style. It’s directed by Suzie Templeton, who’s just a fantastic visionary. It’s such a shame she never made anything after that. We created this incredible hyper-real puppetry. All handmade. We actually had a forest that had 1,700 trees in it. Piotr Dominiak, who became the head of painting for Loving Vincent and The Peasants, was in his mid-20s at the time, painting the backdrops for Peter and the Wolf. Some of my team, we’d been working together for 18 years.

JP: When did you first fall in love with movies?

HW: Yeah, I’m not like most directors or filmmakers. I was more interested in sport and nature, but I loved acting. I loved acting at school. I loved acting. When I went to university, I did academic subjects. I wasn’t [particularly] interested in them. I just did them because I got reasonably good results. I was studying politics at Oxford. And I didn’t really have any interest in my subject. [Though] I was doing a lot of acting and writing for theater, I just couldn’t see myself fitting in with the theater crowd.

I didn’t fit in with the theater people, so I thought I would do film because I like telling stories. It was an impulsive decision. I knew what I didn’t want to do: I didn’t want to go into politics or banking or financing or insurance or be like any of the people who are coming and recruiting at universities. I didn’t want to go into theater. So I just made a decision.

I love[d] Jungle Book, Star Wars, but I didn’t get to see anything other than that. My dad used to watch a lot of John Ford films. He also liked [Michael] Powell and [Emeric] Pressburger, classic British films, and American films. Westerns and stuff like that. Good quality, but Westerns. We used to drink and watch films. We probably watched the same films several times over, like The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and Dr. Strangelove. We watched those quite a few times. They were kind of favorites.

It was really my dad’s films. I queued up for E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial when I was [young], and went to all the Star Wars films, [and] you know, Tunes of Glory. Yeah, I was quite influenced by my dad’s film taste. When I went to film school, it was like a whole new world. Everyone knew about all the European film movements. Every day people would [ask,] “Oh, have you seen this? Have you seen this?” I’d just write everything down and then just watch everything. That’s where I discovered animation. For me, animation was like kid stuff and Disney. It’s all right, but I didn’t like it that much. Apart from The Jungle Book, which I always loved. I was never really into Disney stuff. And then I discovered all this art animation: [Jan] Švankmajer, the National Board of Canada, and Eastern European [animated] films. I was like, “Oh, wow, this is a whole artistic universe I didn’t know existed.”

Animation directors were so much nicer to work with than live-action directors when I was studying producing because they knew how to make films. If you animate, you have to know how to edit, you have to know about crossing the line, you have to know about eye lines. You can’t blag it. If you’re an animator, you can’t blag it. You need to know about the construction of a film, whereas, you know, a surprising amount of live-action directors, at least at that time in the early 2000s, didn’t know about basic lens choices or crossing the line. That’s when I really kind of got into animation.

JP: You said your next film will be about rainbows, but that’s not what I heard about The Blaze, right? It doesn’t sound like it’s about rainbows. Humanity is near extinction, right?

HW: No, it is, it is, I think it’s a very positive film though. It’s set 140,000 years ago at the time that was the bleakest time of Homo sapiens. There was a time in our genetic history when there were only 10,000 surviving genes. Our population was lower than the gorilla population today.

If you were an alien looking at the planet, you’d see the Denisovans — probably half a million of them in Asia — looking like they’re doing pretty well. The Neanderthals never looked like they were doing that well, but with about a hundred thousand or so of them, they were doing better than we were. If you’re looking down at us, you’re probably thinking, “Those ones in Africa, they’re goners, they’re never surviving.”

We went on to survive and outlast, interbreed, or slaughter — whoever’s theory you take — our cousins to create the age of sapiens, the Anthropocene we live in now. All eight and a half billion of us now came from those 10,000. So it’s a story of those people who were among those 10,000.

JP: Will it be a painting animation film?

HW: I think we’re going to do a combination of CG animation and oil painting animation. We want it to be more kind of caricatured and more iconic, and to relate to cave paintings and early sculpture and not as specific. Because, quite honestly, people in Kenya and Ethiopia today are just a tiny amount more genetically related to these people than we are. It’s so far back in time that we’re all pretty much equally related to them.

Comments are closed.