When the band Slowdive came out of a 22-year hiatus with a self-titled album, the silhouetted graphic of a face that made up the album cover possessed a simple, iconic serenity. It was ideally suited for the spacy noise flights of Star Roving, the mellow dreams of Sugar for the Pill, and the melancholic longings of No Longer Making Time. Many a fan who was curious about its origins may have been in for quite a surprise upon viewing its source, the film No. 12: Heaven and Earth Magic (1962) by Harry Everett Smith, a film of manic moods and chintzy sound effects that only resembles the lushness of Slowdive’s soundscapes when left on a carefully chosen pause.

One of the great eccentric polymaths of the Beat Generation and a notoriously difficult individual to get along with, Harry Smith’s fondness for numbering his films chronologically was frequently undercut by his self-destructive tendencies to destroy his own works or re-edit them altogether. (He was known to have thrown projectors out of windows.) Seven of his first ten silent films, from 1939-1956, were later compiled into a work entitled Early Abstractions (1965) and set to Beatles music from their poppiest era, partially inspired by his desire to have their graphic patterns appeal to college-aged stoners. Stop-motion cutout animation was generally Smith’s forte as a filmmaker, and Heaven and Earth Magic finds figures from both 19th-century catalogues and contemporary magazines put through a series of visual twists and turns. It is reported to have initially run six hours, but now only exists in the one-hour version that Smith subsequently trimmed it down to.

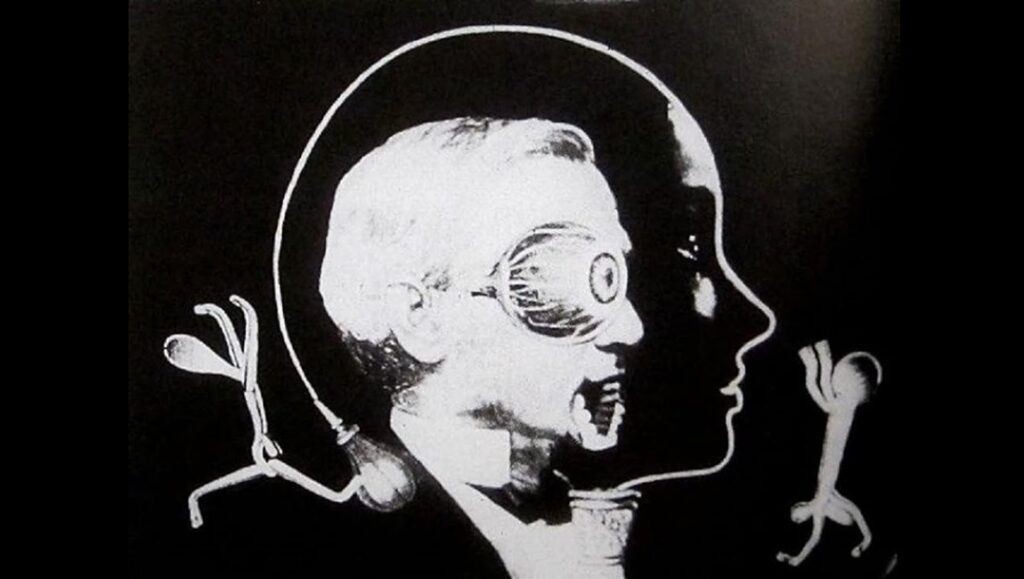

Smith claimed the film was about a woman who went to the dentist for a toothache, ascended to heaven “in terms of Israel and Montreal,” and then “[returns] to Earth from being eaten by Max Müller on the day Edward VII dedicated the Great Sewer of London.” This inspired its makeshift title, which does not appear in the film itself and was coined by Jonas Mekas. What the so-called plot really serves is to justify Smith’s fondness for collecting as many things as possible for his own purposes. It is not so much a narrative as it is a testament to animation’s power to play shapeshifter with found objects, and it can be called one of the few works of animation where truly anything can happen. For viewers accustomed to the medium being a vehicle for simple childhood toy commercials that preach and prattle, it can feel like nothing is happening at all. Body parts are shifted in the blink of an eye and rearranged into nonsense, and the sound effects are nothing but cliché stock noises in the vein of ticking clocks and meowing cats. The blank black spaces that inspired Slowdive’s void-like album cover are frequently filled with creatures straight out of the exquisite corpse drawing game, such as a man with an eyedropper for a face or people seemingly made out of spoons. (Liquid coming out of mechanical body parts is a recurring visual: perhaps the supposed focus on dentistry meant the notoriously unhealthy Smith had an interest in body horror before it became a fully realized idea.)

Smith frequently used color in his earlier films, but No. 12 is entirely monochrome, resulting in stark graphics like the white silhouette of a lizard crawling across the black screen, an elevator appearing to descend via white orbs moving like upward streaks of light, and humans that resemble mannequins for him to play with. They dance and move at a rate of single-frame edits, are combined with other drawings to create new forms of humanity, and break apart very easily to be reassembled again. Experimental film tends to be compared to music at its best, and since this film always takes place in its pure black field, it can feel like a one-hour movement with new elements coming in and out of the void, flowing like the cutout drops of white water. The frame is airtight, but what occurs within is in constant chaos and impossible to pin down.

Terry Gilliam would take plenty of cues from No. 12 for his cutout animations in the Monty Python TV series and its subsequent films — one extended castle sequence feels like it could have very easily been placed into Monty Python and the Holy Grail — while Stan Brakhage frequently showed the film in his classes and took the ideas about abstraction in animation even further when he began venturing into fully hand-painted films. Smith himself would develop even wilder internal logics for his remaining films. An incomplete fragment of his never-finished The Wizard of Oz-inspired project, No. 16: Oz: The Tin Woodsman’s Dream (1967), goes from cutouts of The Tin Woodsman to live-action kaleidoscopic effects. His attempt to one-up Heaven and Earth Magic, No. 18: Mahagonny (1980), is a four-screen work of 140 minutes set to the entirety of the Weill/Brecht opera The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny. Despite his claims of a meticulous structure to the mad avalanche of footage in live-action and animation he assembled and edited over a whopping 10 years, legendary film scholar P. Adams Sitney has dismissed his claims by saying Smith would be listening to Gilbert and Sullivan while making the film.

Smith’s work as a collector and makeshift cultural excavator was arguably more famous than his filmmaking. Paper icon stand-ins of his collections of Easter eggs and string figurines make recurring appearances within Heaven and Earth Magic. His out-of-print 78 rpm folk recordings were turned into the hugely influential compilation record Anthology of American Folk Music, but the vague, anonymous quality of his sound effects in this film resembles that of someone who is going through all the sound effects in a library, unable to afford anything else. Smith was living in the Hotel Chelsea without paying his rent for many years while making most of his films. His pioneering work in anthologizing folk music gave him some leeway, but the bills racked up and his increasingly unsustainable drug and dietary habits gradually ruined his health. Always a difficult individual who introduced himself to Jonas Mekas for the first time by saying “I don’t like you!”, he was known to have a sweeter side, rooted in his desire to encompass culture and art in its totality and entirety out of a boundless love for all the forms it could possibly take. His artistry was rooted in trying to encompass as many ideas as humanly possible through a series of internalized graphic designs and organizational systems. Heaven and Earth Magic is Harry Smith’s ultimate visual conduction of his own form of star roving, from the lights of heaven to the sugary commercials of earth.

Comments are closed.