Let us begin as I started: in media res. Two moths, born far too late to appear in the flurry of wings that made up Stan Brakhage’s classic Mothlight, decided to make their own contributions to the history of experimental film by flying into the projector on the nights that Orders XVI and XVII of Eniaios were projected. The first moth resembled an enormous hair in the gate, and even after they stopped the projector to clean its remains, one stubborn portion marred the top of the frame during the moments featuring a white screen until the reel was over and they could properly remove the rest. The second was not as prominent, resembling something like a scratch or a burn mark and being fairly easy to remove. It was hard to feel unsympathetic to the poor creatures: they were, like us, drawn to the allure of the light itself, before it faded away.

Traveling to the village of Lyssarea in rural Greece to see Gregory Markopoulos’ Eniaios at the site known as the Temenos has been described as the ultimate cinematic pilgrimage, a literal trek to see the magnum opus of one of the most influential filmmakers in the avant-garde canon. For the 2024 edition, about 150 of the most serious cinephiles in the world converged in Lyssarea for Orders XV through XVIII over four sundown screenings. Some (including myself) were first-timers, but many were veterans. Virtually everyone in attendance knew the basic principles of the work and its impetus, most especially the legend claiming the work runs 80 hours in its complete form. Representing Markopoulos’ reconfiguration of his oeuvre into 22 cycles comprised entirely of black leader, white leader, and incredibly brief fragments of images from his past body of work, the making of Eniaios occupied over ten years of his life before his death in 1992.

With only the last four cycles remaining to be reconstructed, it seems likely that Markopoulos’ would-be centenary in 2028 will mark the point where Eniaios is completed thanks to the efforts of many volunteers and archivists, all shepherded by his former partner and fellow major figure of the avant-garde, Robert Beavers. The viewing experience of Eniaios is inextricable from the fact that its quadrennial occurrences (with one exception due to Covid) send up a specific signal to allow for a small but worldwide community to congregate in a common space, although it seems to have grown larger: there were reportedly twice as many applications for 2024 as there were spots.

The site for the Temenos is outdoors and generally requires a half-hour walk, ending in a field featuring a white screen held up by wires and beanbag chairs making up most of the seats. The screening begins when the sun begins to set, and certain sights and sounds are just as common as the portions of black and white leader: the insects, the stars (shooting stars were sighted repeatedly on the first night), the occasional airplane in flight or a satellite quietly orbiting, village dogs barking. The sections of white leader are maybe the best visual demonstration of light pollution that I’ve ever seen: when the screen turns white, the stars seem to disappear. Falling asleep is common, but the bright light of the film and a general inability to fall asleep in the cold open air meant that I cannot testify to what falling asleep to Eniaios is like.

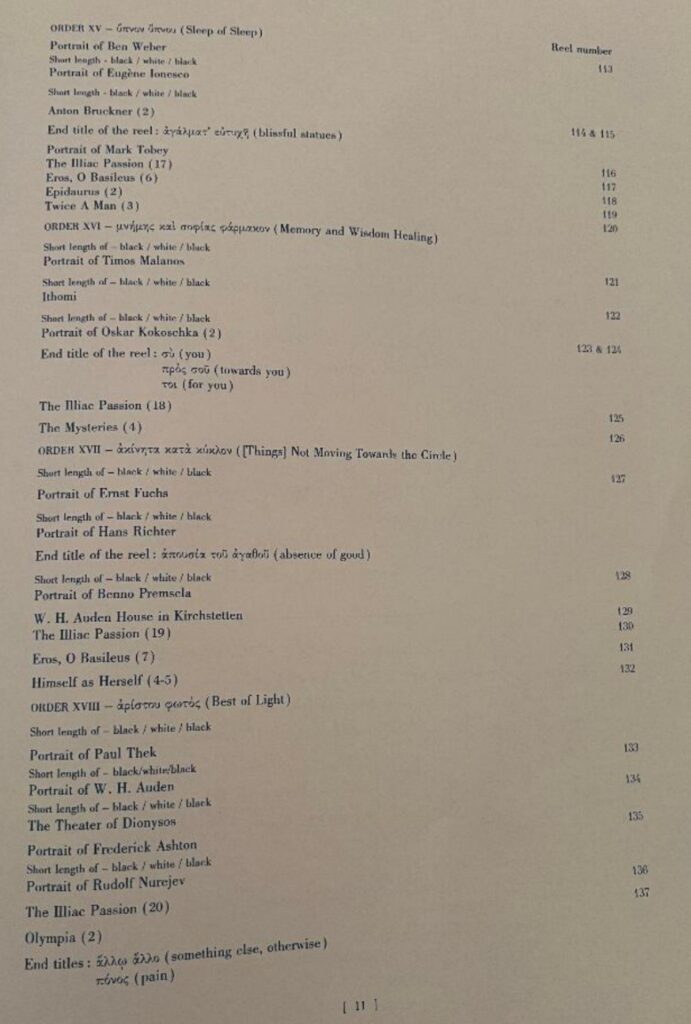

Of the four cycles of Eniaios that were screened, certain structural commonalities became apparent, especially when looking at the program for this year’s edition:

All of the titles listed in Greek never actually appear in the films, and the titles for individual cycles are not particularly illuminating. The end titles for the reels allow for a certain amount of poetic interpretation: the “blissful statues” of Sleep of Sleep are possibly in reference to a repeated flash of what appear to be legs arranged as precisely as carousel poles, while Memory and Wisdom Healing’s “you / towards you / for you” strikes me as a dedication to Beavers and/or the viewer. All the Orders seem to begin with portrait films and location footage, then generally conclude with deconstructions of the iconic images of Markopoulos’ most famous titles: from his academic passions to his carnal ones, all rendered fleetingly but in a sense of total enrapturement.

One title that did not appear in the program notes is nevertheless the Markopoulos film that best summarizes the formal techniques of Eniaios. Gammelion (1968), one of the director’s last films before he went to Greece and withdrew all his titles from circulation, similarly relied heavily on utilizing brief flashes of images alongside leader in order to produce distinctive afterimages on the eye. One does not need to merely look at the sky in order to see stars when watching either Gammelion or Eniaios, although Gammelion’s utilization of a few sound cues to give its economical running time some shape mean that comparisons only go so far. Eniaios is more of a cinematic heart rate monitor: the seemingly monotonous imagery turns out to contain infinite variations in its peaks and valleys, and its duration is that of the speed of life.

Eniaios’ brief resemblances to other moving image works never quite allow for comparisons to directly hit the mark due to its singularity. Some might say its lengthy cycles owe a debt to film serials, those with a more acidic wit might say that this combines with the event quality of its screenings to make it more like television. Some would feel that the screenings at the Temenos transform it into an installation piece, although how much the natural elements are meant to play a part comes down to whether the cycles will screen elsewhere in the future. The use of black-and-white frames is a silent variation on Peter Kubelka’s Arnulf Rainer and Tony Conrad’s The Flicker, while the long-form approach to the projection of monochrome squares is somewhat reminiscent of Paul Sharits’ extended color studies if you bleached out the garish shades. The sequences where past Markopoulos films are deconstructed and expanded makes Eniaios something like Brakhage’s The Art of Vision to those films’ Dog Star Man. Whether one prefers the economy of the shorter works or the slow-motion forensics of the epic collages is largely a question of both personal aesthetic preference and which titles one is even able to access — the ability to actually see 16mm film is becoming increasingly localized, although it seems that DCPs of certain Markopoulos titles have begun to be made. Since I would not recommend Eniaios to Markopoulos novices for the same reason I would not recommend having The Art of Vision be one’s intro to Stan Brakhage, greater access to the Markopoulos filmography will hopefully render Eniaios’ artistic approach more accessible as a result.

For the sequences centered on deconstructing prior Markopoulos films, the effect was frequently like seeing stills for a film one badly wants to see. What little Markopoulos allowed Eniaios viewers to see of the chiaroscuro eroticism of The Illiac Passion, and the youthful glow radiating off a naked Beavers as the titular god of love in Eros, O Basileus, was so enticing that I mostly just wished to see the films in their original forms: both to understand Eniaios’ goals better, and for the simple pleasure of their visual beauty. (Beavers’ filmography includes his own cycle of 18 films, with a title that intriguingly rhymes with his gestures in Eros: My Hand Outstretched to the Winged Distance and Sightless Measure.)

Among the two listed films that I was familiar with, I only saw one go through the Eniaios treatment: the Twice a Man material of Sleep of Sleep was unfortunately announced to have been misplaced, meaning most people who attended don’t quite have a complete picture of that particular entry. Himself as Herself’s appearance in [Things] Not Moving Towards the Circle was the one hint at a greater understanding of what Markopoulos achieved: the hour-long film was given an entire concluding reel of restructuring to itself. Taking out the soundtrack and making the film’s central preoccupations of gendered clothing even more repetitive captured the same moods with different methods, most notably when the leader tricks resulted in afterimages that brought out new colors and unusual shapes, from a white tuxedo shirt and a blue-gold sari.

Whether it was because I developed a greater understanding of the inner workings as it went along or because of issues with Sleep of Sleep that bled into Memory and Wisdom Healing — along with the missing reel, it had to be partially screened the same day as Memory due to excessive humidity on the first night — [Things] and Best of Light struck me as more comprehensible than the first two. That’s not to say Sleep and Memory were lacking in beauty: the former contained striking excesses of black and white leader, while its portraits featured Ben Weber shifting from sitting silently to seeming to yell in a fright wig, and Mark Tobey’s remarkably expressive wrinkled face and fingers. The latter took the most famous shot of Markopoulos’ The Mysteries, of a naked man lying with a skeleton, and drew it out for a small eternity, as if we were truly laying with death.

[Things] featured the portrait that most felt like it had been conceived specifically for the formal methods of Eniaios. Hans Richter is shown at a film rewind bench, and the film’s flickering manages to approximate the sensation of film whirring by as you see flashes of images. Even more critical is the metatextual element of Hans Richter’s early experimental film masterpiece Rhythm 21, a likely influence on Eniaios’ formal approach for being nothing more than a black screen populated by white squares. It’s a perfect homage to Richter, and it was followed by a particularly aggressive use of white leader for Benno Premsela reading a text: words on a page and images against leader both leave their marks on you. The other original material featured an eccentrically costumed Ernst Fuchs, and the lines of the W.H. Auden house turned into something like the window-matte games of Barry Gerson’s underseen Luminous Zone.

The concluding Best of Light featured the most pleasingly logical relationship between the portraits: a five-act parabola of young-old-ancient-old-young, and a great addition to Markopoulos’ better-known homosexuality psychodramas thanks to its focus on his fellow gay artists. Paul Thek is shown alongside a particularly sexual example of his meat statues before we see the face of an elderly, unmoving W.H. Auden. He turns into a statue from the Theater of Dionysus, which is followed from its face to its legs in what might just be a suggestively spread pose, concluding with a series of broken and disconnected feet that transition into the frozen dress shoe of Frederick Ashton. His queen-bitch pose in his living space, occasionally moving slightly, turns into the outright dynamism of Rudolf Nurejev. The great dancer’s movements aren’t even particularly notable in their own right, but the bright colors of the outdoor space he’s in, combined with the motions of such simple actions of putting on a jacket, work in tandem with the flickering afterimages to feel like a testament to the fleeting beauty of youthful movement. Knowing Nurejev would die only a year after Markopoulos from AIDS complications makes the stillness of the final two segments that follow the portraits particularly wrenching: a deconstruction of The Illiac Passion that features solitary bodies frozen in sexualized poses, and footage of the grave-like stones of Olympia. What “something else, otherwise / pain” means is as interpretable as anything else in Eniaios, but the final word reconfigures the meaning entirely, and is as impactful as a single frame of Markopoulos’ images. For all the supposed gigantism of its running time, construction, and the travel one needs to view it, Eniaios and the Temenos are fundamentally an intimate affair, characterized by the silence and stillness of life’s internal revelations.

Comments are closed.