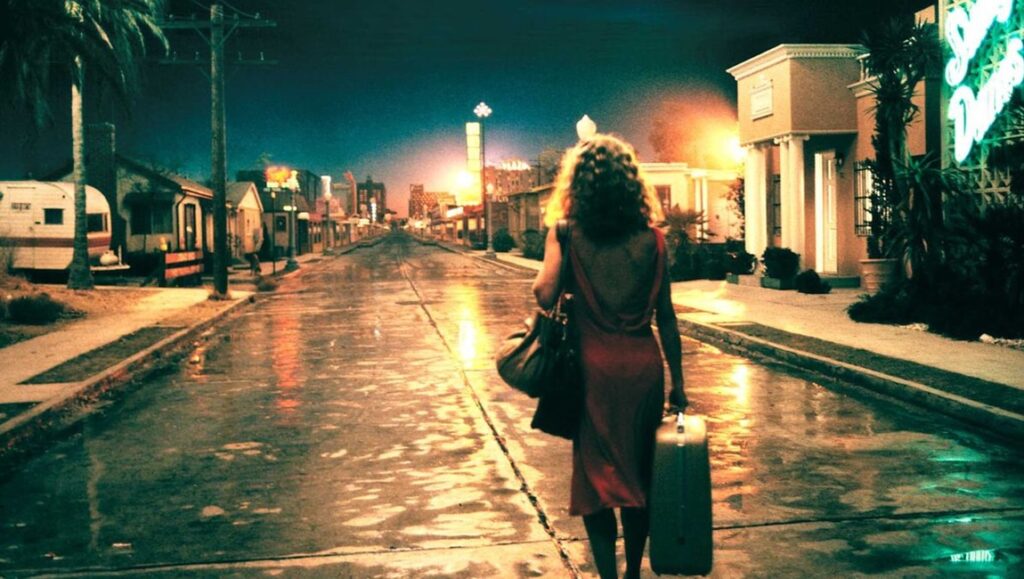

“You know what’s wrong with America, don’t you? It’s the light,” Hank rants to his buddy. “It’s all tinsel, it’s all phony bullshit, man. Nothing’s real!” An understandable sentiment coming from a man who lives on the edge of Las Vegas, that great monument to fakery — a city where you might stumble from the Great Pyramid to the Eiffel Tower, the Statue of Liberty to the Trevi Fountain, all in a few steps. But Hank is more right than he knows. His world isn’t Vegas but a dream of it: painted skies, gorgeously gaudy sets illuminated by impossibly bright lights. This is Sin City as imagined on the soundstages of Francis Ford Coppola’s Zoetrope Studios — a true simulacrum, a fake of a fake.

Hank’s girlfriend Frannie (Teri Garr) works in a travel agency, arranging dioramas in the glittering window — sets within sets — and fantasizing about true escape, a trip to Bora Bora. Hank himself (Frederic Forrest), meanwhile, is a mechanic at the aptly named Reality Wreckers, a junkyard filled with what looks like the detritus of a Hollywood backlot. It’s the couple’s fifth anniversary, and tensions quickly boil over into a fierce argument — hardly their first, we take it. They slink off into the night and swiftly fall, somewhat implausibly, into the arms of their fantasy lovers: Frannie with the endlessly charming cocktail pianist Ray (Raul Julia), Hank with Leila (Nastassja Kinski), a circus performer half his age. “Think she’s real?” Hank asks his buddy. We’re not so sure.

Coppola leans into this ambiguity, relishing the slippage between reality and fantasy. His compositions play with narrative space in imaginative ways; when a pining Frannie tries to call Hank from her friend’s apartment, the distance between them is dissolved by a simple switch in lighting setup that teleports him right beside her, even as he remains sat somewhere across town. Murnau would be proud. Maybe Busby Berkeley, too. One from the Heart isn’t exactly a musical, even if it is wrapped in an original soundtrack — sung by Crystal Gayle, growled by Tom Waits — tangentially linked to the action on screen. But it possesses the spirit of the musical, leaping from the mundane to the sublime, as in the scene where Frannie and Ray’s romancing spills out onto the streets and into an ecstatic flash mob, or when Hank conducts an orchestra of beat-up cars to impress Leila.

Coppola was coming off the back of one of the greatest four-film streaks of any director: The Godfather, The Conversation, The Godfather Part II, and Apocalypse Now, his Vietnam War spin on Heart of Darkness which had its own infamously troubled production. With a spiraling budget and nervy investors dropping like flies, One from the Heart was a considerable gamble on which was staked not only vast sums of Coppola’s own cash, but also his utopian vision for a movie studio of the future — involving video storyboarding, remote direction, editing during production, and even a four-day week. When the film inevitably flopped, it did so spectacularly, pushing Coppola and his studio to the brink of bankruptcy. All that technical bravado, it seemed, had eclipsed the promised romance. “This movie isn’t from the heart,” Pauline Kael wrote, “or from the head, either; it’s from the lab.”

Audiences stayed away, and you can sort of see why. Ostensibly a two-hander, the balance is tipped significantly toward Hank, in whose form we receive a truly detestable protagonist: belligerent, physically controlling, and saddled with a godawful haircut to boot. In one scene, he drags a naked, humiliated Frannie from bed into his car, where he promptly insists she cover herself up. By the time the climax arrives, and Hank rushes to the airport to win her back in true rom-com fashion, we are practically screaming for her to leave this piece of shit. And she does — for a moment. But minutes later, she’s back at the door, back in his embrace. Cue music box, end curtain. What a bummer.

Then again, it couldn’t have ended any other way — it literally couldn’t, Coppola seems to be saying. We could, of course, dismiss One from the Heart’s icky sexual politics as sexism, pure and simple. But it might also be that accusations of paper-thin characterizations and bogus resolutions miss the point. Even in what feels a more real, rougher musical — a deconstruction of the classical Hollywood musical through sheer excess — everyone lives their lives the only way they know how: like a movie. All these characters are archetypes, their resolution is predetermined. Even more perfectly than its hometown of Los Angeles, the film suggests, Las Vegas is movies: all the world at your fingertips, escapism through artifice, a place where dreams come true — for a price.

I was mid-way through writing this piece when I learned of the death of Fredric Jameson, the titan of Marxist criticism who wrote so memorably on the America Coppola conjures here — and who, it should be added, has been consistently undervalued as a film theorist in his own right. To my knowledge, Jameson never published anything about One from the Heart, and yet it contains all the contradictory elements of the postmodern work of art as he described it. It is, on one hand, exemplary of what he identified as the “nostalgia” film emerging in precisely this early ’80s period — a pastiche of past cinematic styles, concerned solely with its flattened, commodified surfaces. But Coppola’s film also carries both an echo of the modernist spirit of formal experimentation and an implied critique of the “phony bullshit” even Hank himself ultimately embodies.

Though it was a failure in its time, One from the Heart survives as Coppola’s blueprint for some other possible cinema, both onscreen and behind the camera. True to the spirit of Las Vegas artifice, it’s at once wondrous and repugnant. In a culture in which productions of this magnitude and ambition are usually test-screened to death in search of the likable, the palatable, perhaps we should be grateful that this beautiful, ugly film escaped unscathed.

Published as part of Francis Ford Coppola: As Big As Possible.

Comments are closed.