In the grips of the beating sun, we see a group of young radicals — ranging from Black Power activists to draft dodgers — attempting to traverse roughly 50 miles of the Californian desert’s barren landscape in order to reach an American flag. In doing so, they will avoid lengthy prison sentences cast down upon them for what the Nixon administration defines as attempting an insurrection. Of course, like everything in America, the system is rigged against them, and as they walk across the desert, slowly dehydrating, armed police officers chase them in vehicles — with the sole intention being to not let a single person reach the finish line. Alongside these images are ones of a separate group of activists, being tried by a collection of governors, senators, and civil servants, all awaiting their persecution, forcing them to become the next in line to be sent to the aptly titled Punishment Park.

Despite these images looking and feeling like genuine reels from a documentary, with the sweat from the beating sun and dust from the sand dunes lending wholly a sense of the corporeal, they are, in fact, fictional. Peter Watkins’ 1971 mockumentary delivers a startling vision of alternate history, one that is only a slightly exaggerated version of actual material reality in America. Punishment Park heavily relies on its own believability to instill a sense of shock and outrage within its audience, often feeling closer to replication than dramatization. The film acts as an extension of Watkins’ signature pseudo-documentary style, which he began shaping in early shorts such as Culloden and The War Game, and which take events such as the 1746 Battle of Culloden or a nuclear war and treats them as if they were documentaries being filmed as the events actually occur. In the case of Punishment Park, we follow a European news company attempting to capture the Nixon administration’s controversial penal system. Here we see Watkin’s style eroding the thin line separating reality and artificiality, until both eventually collapse and become indistinguishable from each other.

Punishment Park’s images of police brutality and activist crackdowns feel like a specter that still looms over American society today: newsreel footage of the police’s brutal assaults on Black Americans; images of riot squads being used to suppress protests. But more obviously, it continues to reflect the state’s response to Palestinian protests, which have seen hundreds of thousands of Americans rally against their own governments’ continued support for the apartheid state of Israel and their continued genocide against the Palestinian and now Lebanese populations. Whilst the protestors in the film are largely fighting against America’s unjust and deeply evil war in Vietnam — which saw countless civilian deaths, the destruction of infrastructure, and war crimes committed — their words resonate with America’s complacency in yet another genocide. One protestor cries out to the jury after being accused of acting immorally, “War is immoral, genocide is immoral, poverty is immoral,” a collection of statements still depressingly relevant to contemporary American politics, with the film providing a bleak look into how little has changed with regard to both foreign and domestic policies.

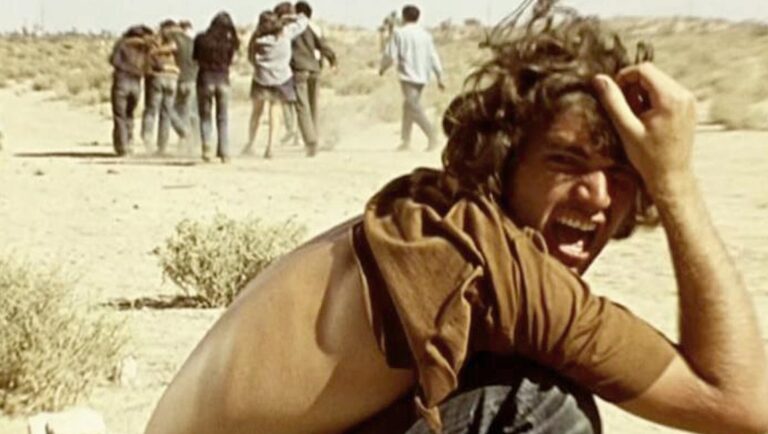

However, despite being an object to convey Watkins’ rage and bitterness toward the state of American politics in the 1970s — be it the war in Vietnam, police brutality, or the demonization of “radical” politics — it’s also a beautifully made film, specifically in terms of both editing and composition. Punishment Park highlights Watkins’ fixation on capturing the human face, often filling the frame with a closeup of a singular face: a shaken national guardsman who is trying to make excuses for shooting an unarmed person; an activist being driven to the depths of the desert knowing they might not return; a police officer’s emotionless expression while discussing killing people in the field of duty. Watkins uses these close-ups to further express the characters’ own political views, with the collision of these views becoming the driving force of the film’s conflicts. Further exasperating this is the fact that most of the cast is made up of non-actors who let their own personal views — be they conservative or leftist — bleed into their characters on screen, aiding the film’s prevailing sense of realism.

Elsewhere, Watkins uses editing to create a rhythm of continuous conflicts, often cutting between the reactions of different characters to convey how each of them feels about the specific scenario: despair at witnessing police brutality or smugness after detaining an activist. Through montage, Watkins exposes the power dynamics set within capitalistic structures. By cutting between the different characters in rapid succession, we are able to see who is in control: the officers of the State have the weapons, food and water, whereas the brutalized and dying prisoners have nothing but communal strength. When we see groups of activists being tried, the camera cuts rapidly between a collection of different speakers, including the defendants and the numerous people on the jury. Despite the multitude of different characters and voices, in execution, this never feels overwhelming, with Watkins giving enough time for the activists to fall into monologues about their own feelings on contemporary America.

More than anything else, what still registers most palpably is how tangibly full of rage and sorrow Punishment Park is, with Watkins’ feelings coming out in full force during the film’s final moments. Even at the end, where groups of sole survivors have banded together and made it to the flag buried deep within the mountains, they are violently attacked by police officers waiting for them. Their only crime is the ability to actually beat the State at its own game, despite every possible force working against them. As the last protestor is beaten and dragged away, images of the police cut across the screen with the faux documentary filmmakers — who, at this point, have become an extension of Watkins himself — demanding a reason for their actions. But despite all of this being “caught” on camera, the fascists can only whimper up a response falsely asserting that the protestors charged them first. With how much State violence has been recently captured on camera — whether at home through barbaric border policies or abroad with the destruction of hospitals in Gaza, for instance — and how many officials still deny them, one can only despair at how little has changed since these “fake” images were captured 50 years ago. The borders of Punishment Park are bigger now than ever.

Comments are closed.