The year before he starred in Witness — Peter Weir’s acclaimed drama about a cop sent to protect a young Amish boy who witnesses a murder in a train station bathroom (a traumatic first journey out of his hermetic vicinage) that became the eighth-highest grossing film of 1985 and earned its marquee megawatt his first Oscar nomination — Harrison Ford returned to one of his two enduring iconic hero roles: Indiana Jones, in The Temple of Doom. This culmination of the first phase of his career, which found the actor playing incorruptible and unstoppable American heroes in blockbusters, fighting off fascists in the desert and in space, now saw him defeating cultist enslavers of children, and becoming a surrogate father figure (very Spielberg) to hundreds of abused kids. An impassioned homage to the Republic Pictures B-grade serials of the ’30s and ’40s, and the essential Hollywood blockbuster sequel, Temple of Doom is perhaps the film Ford had to make to shake free the shackles of megastardom. Spielberg and George Lucas crafted a series of astonishing and absurd set pieces strung together like pearls glistening on string, with little care or concern for character depth or meaningful ideas; Temple of Doom is a film unburdened with political consciousness or sense of decency, instead flaunting an unalloyed childish sense of fun, while remaining cruel and violent enough to help engender the PG-13 rating after kids left theaters crying and confused.

What makes Temple a great film is that it repudiates the blockbuster respectability of The Empire Strikes Back and instead basks in glorious, stupid, tasteless fun which, while based on the archaic entertainment of the serials, also anticipates the dominant style of movie culture in the decades to come. It’s a film made by unhappy man-children, grotesque and puerile and ravenously fun. In its technical and imaginative braggadocio, the mean spirit lingering over every scene like a bad aura, and its preference for outlandish spectacle over emotional resonance, Temple of Doom is maybe the best dumb blockbuster sequel; as such, it left Ford with no other choice than to move on and challenge himself. From 1980 to 1984, Ford only appeared in films blessed (and, in a way for Ford, blighted) with grandiose budgets for grandiose visions. Movies made to be popular. Movies made for movie stars. With Witness, Ford took his first big step toward being taken seriously not just as a hero boys want to be and girls want to be with, but as an actor — playing, of course, another hero. This good guy, though, is rooted not in the rationale of sheer cinematic escapade and spectacle, in the way of Indy and Han Solo, but in a perhaps jejune, though charmingly earnest, imagining — cinematic still, but a slower, smaller, quieter kind — of a specific reality, alien to us. It’s one which we have seen in pop culture, and heard about, and joke about, but have rarely experienced ourselves, beyond maybe buying some of the sturdy furniture they make: the Pennsylvania Amish.

An Amish man has died. His community gathers, a mass of black-garbed grieving friends with heads covered and beards robust packed into one modest, cleanly-kept home to say goodbye. Then we see these odd Amish, willfully bereft of all modern conveniences and purposefully living pitifully. In their horse and buggy trodding along down the modern asphalt road, a semi-truck and many cars puttering along at an agonizingly torpid pace behind them, they coexist with a present which they ignore, and which ignores them. Images of swaying green fields and the buggy and the cars transecting the screen recur in the opening scenes. The dead man’s widow, Rachel (Kelly McGillis), and her son, Samuel (Lukas Haas), hop a train to visit her sister, passing through the modern Gomorrah of Philadelphia. Here, the impious outside world cannot be ignored; its evils will invade theirs.

In the train station, a beguiled Samuel gazes with awe at the strange people and foreign technology around him, gazes with twinkling wide eyes at Walker Hancock’s bronze statue of the Archangel Michael, patron saint of cops and soldiers, looming with heavenly vigilance over the vast station, his pedestal adorned with the names of all 1,307 railroad employees who died in World War II. Women who see Samuel call him “cute.” But then Samuel goes to use the bathroom, and witnesses two men murder a third. One, played by Danny Glover, stands out to Samuel because he has never known a Black man before. Samuel represents the child who inevitably loses his innocence when first confronted with the ugliness and violence bred prodigiously by this country. And the police are the bad guys! (Witness is worth watching alone just to see Danny Glover as a man and cop whose wickedness is so much the opposite of the kindly, too-old-for-this affability for which he is often known.)

In the aftermath of the murder, John Book (Ford) is assigned to the case. He protects Rachel and Samuel. He introduces them to hot dogs, figures out what’s going on, has a brief gun fight (in which the bullets never seem to strike the cars they’re hiding behind, though John does catch one himself), and, wounded but too proud to get help, goes back with Rachel and Samuel to their farm when the corrupt cops decide to come after them.

Witness‘s sometimes incongruous, sometimes too-safe visualization of the film’s naive ideas — and the glacial pacing Weir uses gorgeously to sustain a hallucinatory air in his best films, like in Picnic at Hanging Rock, is here, as in many of his mainstream Hollywood movies, too often a crutch on which he seems to fall back when unsure of how to bring middling writing to life — are held together by the melodious photography of John Seale. Seale has had a dizzyingly diverse career, from the Oscar-ready respectability of The English Patient, to The Talented Mr Ripley, a film disguised and sold misleadingly as Oscar bait but is actually an edified telling of a psychosexual story of obsession, identity, and murderous passion, to the variegated vibrance and resplendent, rambunctious maximalism of Mad Max: Fury Road. Again, versatile. Here, the DP finds not just the obvious beauty in Weir’s distinctive style, but makes scenes of B-movie bad guys (not Weir’s style) flow tonally with Ford and McGillis swooning and the Amish going about their quotidian duties, in their universally-recognized modest outfits and demonstrating the resolute dedication universally expected from such mysterious people who are, for lack of a better word, iconic — easily identifiable in look and attitude, as if they’re film characters rather than real people. The ethereal poetry of Maurice Jarre’s (David Lean’s vital accomplice on Lawrence of Arabia, Doctor Zhivago, and A Passage to India) music, possessing hues of Vangelis, pairs so prettily with the imagery that you may forgive the film its childish, or perhaps more accurately child-like, notion of profundities, which earned the film a Best Original Screenplay Oscar.

It’s Ford, though, who inculcates Witness with its lasting power, delivering a performance which does not dazzle in the mega-acting histrionics way, but instead in its beaten-in honor and exhaustion and stubborn moral integrity which, at last, shows viewers a human Ford. He still brings his cockeyed grin and unpracticed masculine suavity to the show, but has toned down the cockiness into something more like a genial insinuation of middle-age grumpiness, a been-there-seen-that kind of guy; in his character, who is not particularly compelling on page, Ford finds a lovely hope, shining not unlike the hot golden sun that hangs mighty over the fields filled with men pouring sweat into the dirt and grass and homes erected by the many hands of a community. McGillis’ visage, unsullied by make-up, espouses deep, unspoken feelings, shared not even with God, perhaps. You can see, in the stoicism Rachel wears like a protective mask to keep the strange man and his modern world at bay, and in the annoyance she can’t hold back, and the smile she finally permits, her evolving emotions, and the frightening, then exciting, curiosity and passion she develops for a man with such an unacceptable demeanor who nonetheless has begun to stir her soul.

Witness may not be a great film. It’s too simple and ingenuous in its ideas and the trajectory of the plot, and Weir is seemingly less interested in its requisite action-thriller elements. But it’s nonetheless a seminal one in the history of cinema, freeing Ford from the encumbrance of blockbuster heroism and showing us — showing producers — that he is just as adroit at serious acting as he is at valiantly kicking evil’s ass. His subsequent dramatic roles — not to undersell his forthcoming comedic work, where he used his grumpiness to wry effect — all stem from what he did in Witness. And an actor, he only got better and more nuanced from here.

He reunited with Weir the following year on The Mosquito Coast, a film which lives or dies on Ford’s ability to understand and convey the desperation of a brilliant man who, disillusioned with the false promises of America, uproots his family and takes them to the innominate riot of verdance found in the Central American jungle. There, in a lawless tangle of foliage and the alien customs of the locals, he finds a purpose for his life — a purpose which becomes a dangerous obsession. The film is spiritually kindred to Witness, then, with both concerning a man who finds himself in foreign territory and contending with the intrusion of modernity. Only this time, the alien environment wins. Ford’s genius inventor Allie Cox tries to build a utopia which will offer everything the fallacious American Dream does not, including making a machine that creates ice in the environment’s oppressive heat, a concept everyone finds wondrous. But problems naturally arise. A reverend shows up to convert the locals, and Allie, growing draconian, commences an ideological clash, which, along with his increasingly intense desire to create the perfect society and his unreasonable demands of everyone around him, turns the disillusioned dreamer into something of a mad God ruling over an empire whose downfall is his own doing. The Mosquito Coast offers Ford’s most complicated performance up to that point in his career, and he pretty much single-handedly saves the movie from its own confused, even hacky, writing and Weir’s complacency (he shows little of the visual lyricism of his best films).

Two years later, in Roman Polanski’s deceptively intricate Frantic (a bona fide box-office bomb in 1988), Ford, as in Witness and The Mosquito Coast, again finds himself in trouble in a strange land. He plays Richard Walker, a respected doctor running around Paris looking for his wife, who soon finds himself entangled in a conspiracy beginning with the wrong luggage and involving a tacky tourist souvenir statue, a playful plot point befitting a story about a lost American who doesn’t speak French or know where anything is, and also a fun foil to Indiana Jones’ pursuit of rare antiquities. The film is an unhurried thriller, with scene after scene of Ford failing to convince anyone that something foul is happening and asking questions people can only answer partially and vaguely. Predominantly composed of longish medium shots capturing all needed information and relevant characters in the frame together, with small movements and adjustments to keep everyone on screen rather than relying on much cutting, Frantic uses its modesty to execute a slow, intentionally under-exciting twist on Hitchcock. (It isn’t until Ford meets John Mahoney’s liaison at the U.S. embassy that we get each man in separate shot/reverse-shots.) It’s a serpentine story, told with mostly simple, efficient visuals, and one fundamentally reliant on Ford’s subtle performance as a man who is perpetually worried and never in control of any situation.

In Frantic, Ford possesses the perseverance of his blockbuster heroes, but little of their skills. Instead, his defining quality is that he loves his wife, which makes this the actor’s first “wife guy” movie. (He would play an anti-wife guy in What Lies Beneath.) With scenes lampooning the classic Hitchcockian mystery — Ford operates as a kind of anti-Cary Grant here, in his ugly suit and with his perpetual befuddlement — and everything enveloped by a nagging sense of paranoia, Polanski realizes Paris a tangle of narrow streets leading only deeper into mystery, a drab city of useless bureaucrats who can only provide paperwork and seedy rooms populated by unsavory characters who all might know something Richard that does not. He might be smart and resourceful and absolutely undeterrable, but he’s still a mostly helpless sap playing sleuth. (Consider, as a counterpoint, how deft he is at solving his wife’s murder while evading some very dedicated U.S. Marshalls in The Fugitive.) When a man in a packed bar, hazy with smoke, asks if he’s looking for “the white lady,” Richard, thinking that the man means his wife, follows him to the bathroom expecting information. Richard instead ends up doing coke, and is clearly not a fan. (He buys some anyway.) Oftentimes, he doesn’t even seem to know what questions he should be asking all these people he tracks down. It takes a French woman with long legs whose luggage theirs was mixed up with, which set off the whole mystery, to usher in resolution, though her real role in everything remains unknown, and a source of suspense. Indiana Jones travels the world, never stumped or in the dark about any culture; Richard can’t even order a coffee.

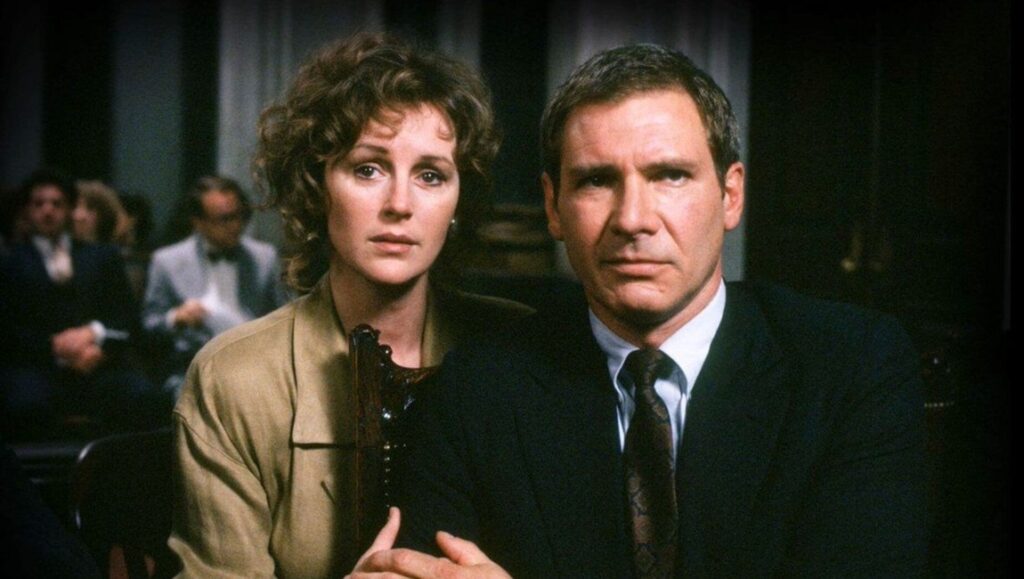

All of this leads to 1990’s Presumed Innocent, where one can find Ford’s most brilliant moment as an actor, in one of the great endings to any studio movie due to how unexpected it is. This arrives not just in a plot twist sort of way, but in our witnessing the final epiphany for Ford’s emotionally tender lawyer, Rusty Savage, now declared innocent — which comes as a relief to viewers, despite us still not knowing if he did it — an epiphany Rusty didn’t want. It’s a moving, beautifully melancholy scene, and arguably reflects Ford’s knottiest role (producers were reluctant to cast him because they didn’t think audiences would like Ford as a less-than-lionhearted guy). It consists of just one terse syllable swollen with pain, choked out with a sense of defeat and emasculation and utter heartbreak that Ford had never delivered before. A look of hate. It’s the only time he’s played a loser. We think of Rusty pitifully begging a woman to take him back, and we see the desperate longing on the face he can’t keep from quivering as she coldly rebuffs him without even giving him her full attention. This man is no hero. Rusty is framed off-center in every shot, except when he is in profile for a short scene of him face-to-face and furious with the man who will oppose him in court. He often sits alone looking distraught, moments and facial expressions which, on a second viewing, tremble with sincere sadness, scenes of a man who may not only lose his job, but who has been rejected by a woman for whom he was willing to ruin his family. He sits sadly, alone, thinking about happier days with her, the woman he can’t get over, unable to accept that she viewed him simply as a means of advancement. It isn’t love he feels for her: it’s obsession.

In the film’s final scene, his wife explains, in a quiet, serious tone and with poetic phrasing, why she killed the lecherous woman: she did it to save their marriage. “Saved?” is all Rusty says, eyes drowning in tears and his face contorted into a look which silently screams out in agony and baffled anger, one word telling us everything. We know, in this moment, that Rusty would rather be with the woman who used him, who never loved him, than the wife who killed just to get his attention, an act of dangerous love for a man who betrayed her. With that one word, we finally know who this man is. After two hours of hoping that he is innocent, because he is Harrison Ford, after being taunted with one misleading revelation of Rusty cleaning the bloody hammer in the dark-as-pitch basement, we believe are the end, and are left feeling hurt that cinema’s great hero murdered a woman because she dumped him. But then this moment is suddenly usurped and revealed to be an untrue assumption, a misinterpretation of visual storytelling, with an even greater revelation arriving in a softly spoken confession, expressed with more relief than guilt. But now, at the end, after one word, and even though he is innocent of murder, we might like this man, as manifested by Ford, less than ever. That’s the Ford effect, and we have only to look back to Witness to see how he got here, and what was ahead.

Comments are closed.