Eddington

When the world turned to shit approximately five years ago, satire marched ahead, determined to outpace the banality of lived reality. Old-school broadcasts and appeals to reclaim the political center lacked the traction of identity politics, the ironic pizzazz of deep-fried memes, and the virulence of everyone being everywhere all at once, doom-scrolling and tweeting from their living quarantines into deadly oblivion. Now, arguably, the satire industry is busy playing catch-up with the shit it spawned. Irony’s a poison, sincerity a fool’s rush-in, and any hint of the contemporary universe, violently expelled from the promise of nostalgia, meets with a reflexive shudder.

An exercise for the reader, then, is this: should Covid-19 and the past five years be satirized at all? Premiering under a second Trump administration and amidst the pandemic’s ideological fallout, Ari Aster’s Eddington goes for broke with its hysterical yet surprisingly empathetic cross-section of American ressentiment. A microcosm of the nigh-irreversible divide between left and right, the fictional town of Eddington, New Mexico, also straddles the polarized terrain between those subscribing to singular Truths and those who don’t. The town’s sheriff, Joe Cross (Joaquin Phoenix), is affable enough and generally competent with the management of law and order, with two deputies at his beck and call. But small-town logic can’t quite survive a global pandemic, much less the infectious tendrils of a router connection. What begins with the sheriff’s disgruntled resistance to the mask mandate declared by the town’s mayor, Ted Garcia (Pedro Pascal), rapidly morphs into a political fracas by all and none, for all or nought.

The beef between both figures of authority is personal. Ted spouts vapid, quintessentially liberal rhetoric, welcoming investment from abroad in the form of a proposed data center. (Never mind the energy consumption or the structural unemployment, or the otherwise rote acknowledgements of stolen land.) He also may have impregnated Joe’s wife, Louise (Emma Stone), when she was underage; her catatonic state and constant paranoia, the film implies, could stem from related and unresolved trauma. Joe, meanwhile, quickly escalates his vitriol and falls into a cycle of impulsive action, contesting the upcoming mayoral election with nothing but a makeshift campaign vehicle (his pick-up), his two underlings, and Louise’s increasing withdrawal from his orbit. For a good third of Eddington, the stakes are built around this relatively straightforward antagonism, buttressed by the predawn cracks of conspiracy mumbo-jumbo and Covid skepticism voiced by, among others, Joe’s mother-in-law (Deirdre O’Connell).

But Eddington doesn’t stop there, and taking the risky gambit of using the death of George Floyd as a catalyst for the acerbic carnage that ensues, the film propels itself on its sheer bite, descending into an indulgent if also intensely entertaining potpourri of absurdity. A gun-toting Western with Instagram and TikTok as its central mediums alongside several slurs to boot, Aster’s fourth feature will undoubtedly come under fire for playing it safe and irresponsible all at once, taking aim at both the heavy hand of performative politics as well as the heel of unchecked and unbridled brutality. This view, however, harbors the implicit assumption that satire as an interpretive category always holds post hoc; the collective madness of Eddington, in contrast, hasn’t quite withdrawn its psychological imprint, and the sheer range of its talking points presents a deliberate quagmire in which we — the self-assured arbiters of hindsight (“20/20,” the film’s tagline reminds us) — are meant to stew. Initially rumored to be a zombie flick, Eddington does not exactly head in that direction, but the literal state of things it intuits, coupled with the unsettling currency of its register, threatens to make figurative zombies out of us all. — MORRIS YANG

Actor-turned-filmmakers seem to be the highlight of the 2025 edition of Cannes, but Official Competition newcomer Hafsia Herzi — already with two feature films under her belt — clearly plays in a different league. In the literal sense, too, as the Dickinson-Johannsson-Stewart trio has been given lovely and encouraging spots in the Un Certain Regard section by Frémaux’s team. But for those unfamiliar with the festival’s inner workings, The Little Sister is one of those films that make you wonder how it made it into the Official Competition.

Adapted from Fatima Daas’ eponymous autobiographical novel La Petite Dernière, the film follows Fatima, a 17-year-old closeted French-Algerian teenager, as she navigates a process of self-discovery and comes to terms with her lesbian identity — an experience that stands in tension with her cultural upbringing and religious beliefs. While Herzi’s approach to her protagonist, combined with Nadia Melliti’s grounded performance, demonstrates emotional intelligence and sincerity, the film’s latent instrumentalization of identity politics and its occasional narrative sloppiness result in a half-baked work — a structural weakness it shares with Robin Campillo’s Enzo, which also premiered in the Directors’ Fortnight and similarly explores queer identity as a process of discovery.

We meet Fatima in the spring, as she prepares for her high school qualification exams. Usually framed in interiors tinted with dark shades of blue, her introduction to the film conveys a sense of routine that seems to both protect her and render her invisible. She does her morning prayers, goes to school, hangs out with an all-boys group — the bullying type — and plays football. A rare case of a socially accepted tomboy, it’s her hard work that compensates for her perceived lack of femininity in the eyes of her family. She also has a painstakingly courteous Muslim boyfriend who hopes to move their relationship forward in halal ways.

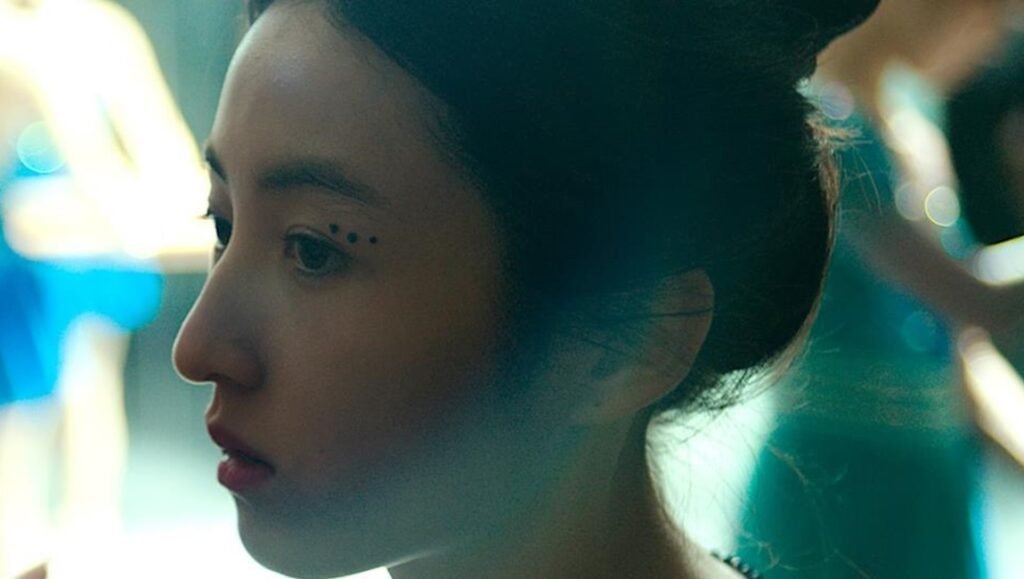

For Fatima, being normal serves as a form of protection — until it doesn’t. During a class argument, someone calls her a “lesbian” — the first breach that reveals something hidden, prompting her to confront parts of herself she had kept buried. That’s when she downloads a dating app and begins meeting women under false identities. Herzi is at her strongest in depicting Fatma’s “undercover” trysts, focusing above all on the ways she seeks self-expression through invented names and shifting personas. Melliti skillfully captures Fatima’s restrained curiosity and the cool butch performance that conceals her inexperience.

Yet Fatima’s interactions with her entourage — whether with her family, her friends, or during her brief nightly encounters — lack a natural flow, a casualness in their rhythm. Herzi is a filmmaker who plays it safe, avoiding risky choices. From her decisions in framing, blocking, and editing to the venues where the characters appear — one of them being La Mutinerie, the emblematic lesbian bar no French queer person could fail to recognize, also featured in Anna Cazenave Cambet’s Un Certain Regard film Love Me Tender — Herzi tries a little too hard to deliver a polished queer representation. Wanting to make a film that would prompt audiences to say, “Finally, a film that gets the lesbian coming-of-age trope right,” might sound good on paper and is a valid ambition, especially given the current state of French cinema — but this deliberateness weighs so heavily on the film that it ends up overshadowing its main character.

The most dissatisfying instance of this deliberate cautiousness comes in the relationship between Fatima and Ji-Na, the nurse she meets at a medical center where she goes for her asthma, and with whom she later goes on a date. Played by a luminous Park Ji-min, Ji-Na represents the first authentic and romantic relationship Fatima dares to pursue. The scenes of them flirting, eating and slurping noodles, having sex, hugging, and kissing each other joyfully at a Pride parade quickly turn into a game of “spot the reference” for connoisseurs. In the third act, Ji-Na suddenly announces that she no longer feels well in the relationship, leaving Fatima to silently grapple with her prematurely broken heart — turning the entire course of their relationship into a direct cinematic quotation of Abdellatif Kechiche’s Blue Is the Warmest Color. Herzi’s recourse to these easily identifiable references stems less from a desire to disown Kechiche than from a will to rework and readjust his gaze — to show how a lesbian relationship should have been depicted instead.

The attentiveness of Herzi’s camera when filming queer, racialized bodies surely won’t go unnoticed. The Little Sister seeks to assert the female, or rather, queer gaze to every inch of its core — but it remains a gaze that is paradoxically “correctional,” dependent on what it strives to free itself from. Herzi’s latest is a counterpoint film that eats its own tail, so to speak. — ÖYKÜ SOFUOĞLU

Militantropos

In the wake of the Russian full-scale invasion on February 24, 2022, a Kyiv-based auditorium turns into an ad hoc military classroom. Civilians take turns studying the mechanics of semi-automatic rifles, loading up their cartridges with ammo, and taking them outside for their very first weapons training. One can only assume that, out of necessity, many of them will have to become much more proficient warriors in the not so distant future — in this regard, Mstyslav Chernov’s harrowing frontline documentary 2000 Meters to Andriivka, which screened during the “Ukraine Day” at the start of this years’ Cannes Film Festival, functions as an eerie flash-forward.

Here, then, we can already see in real-time how the central thesis of Militantropos, the first installment of a documentary triptych by TABOR Collective (consisting of Alina Gorlova, Yelizaveta Smith, and Simon Mozgovyi), is developed. Fusing the Latin milit (soldier) and Greek antropos (human), this trio of Ukranian directors describe through a series of intertitles that the portmanteau of the film’s title refers to “a persona adopted by humans when entering a state of war.” Foregoing the character-driven narratives of many of their filmmaking peers in Ukraine, Militantropos instead captures how an amorphous collective is tasked to embrace a new identity in the aftermath of war.

Much like Olha Zhurba’s masterful Songs of Slow Burning Earth, Milantropos plays like a sprawling observational documentary that ventures into the shifting subconsciousness of a country and its people. Mostly framed in static shots, the pensive cinematography constantly seeks to envelop human beings in their urban and rural environments. Instead of singling out individuals as clear-cut heroes in a linear narrative, the film takes a more abstract turn by exploring the delicate interplay between men and nature against the ever-evolving backdrop of war. And just like the citizens of Kyiv evacuating the capital city at the beginning of Milantropos, the film itself traverses deeper into the heartland, gradually removing itself from stark realism toward affective expressionism.

Even though the color grading of the film is desaturated to the point of grim miserabilism, there is still a painterly quality to the insisting greyish hues. TABOR Collective extracts natural tension from their stark compositions of jagged trees, depleted sunflower fields, mist-covered meadows, and dilapidated country homes. It invokes a time-worn mysticism that seems to be ever-present in the forlorn and wistful landscapes. When bursts of color do enter the picture, it’s because of the engine that propels the film to something greater than just the sum of its many parts. The war machine at the heart of Militantropos produces the most beautiful and scary imagery: scorched horizons ripple in the background of the frame, the luminosity of military surveillance equipmentLED-screens pierces shots with artificial lightning, and the violent reds of nightlights on soldiers’ helmets jump around with expressionistic rage.

The most alarming sequence of all filters a shot of soldiers sneaking through a forest at the border of the frontline through striking infrared-like pixelation. The uncanny textures of this nightmarish image are the rare example of when Militantropos truly succeeds in finding a visual language that speaks to the convergence of humans and soldiers. Unsurprisingly perhaps, it’s the single moment that most strongly recalls Alina Gorlova’s magnum opus This Rain Will Never Stop (2020), arguably the best Ukrainian war documentary made so far. Garlova’s atmospheric black-and-white film is composed with such clarity and edited with such ferocity that it managed to capture the war-scarred psyche of humanity on a near metaphysical level. It’s this exact sensation of cinematic transcendence that is lacking in Militantropos, as it feels like the directors are still in search of the connective tissue that can tie their project together.

Possibly due to the collaborative nature of Militantropos, this first installment of TABOR Collective’s trilogy at times feels weighed down by its huge ambitions. On a formal level, the directors do deliver a meditative piece of cinema that captures the durational effects of war. Conceptually, however, Gorlova, Smith and Mozgovyi still lack the sharpness that is needed to translate such a grand cinematic endeavour into something that bursts with immediacy and urgency. Nonetheless, the unique approach of Militantropos leaves one wondering in which novel direction TABOR Collective will head next. — HUGO EMMERZAEL

Girl on Edge

There are two kinds of cinephile: those who hear a movie described as “Black Swan on ice” and sneer, noses upturned, their one-line, one-and-a-half star review already written in their head; and those who hear the same thing and think, “hell yeah, let’s go!” Judging by the French-language reviews on Letterboxd, the Cannes Film Festival has an abundance of the former. But this writer, for better or worse, lands in the latter camp. Viewers likewise inclined, then, should get hyped for the best movie about youth sports we’ve seen in years.

Wendy Zhang Zifeng, a child actress with credits in films like the Detective Chinatown series, Oxide Pang’s Andy Lau vehicle High Forces, and Feng Xiaogang’s disaster film Aftershock, plays a young skater named Jiang Ning who is training for the last big tournament of the year: win and she moves on to the world championships; lose and her career is over. Her mom, Wang Shuang, also her coach, is tough and demanding. A former skater herself, she pours all the frustrations of her own failed career onto her daughter. She’s a nightmare of a stage mom, alternately biting in her criticisms or flat-out ignoring her daughter in favor of other skaters. Zhang is 24 years old now, but it’s unclear how old her character is supposed to be: with her slight skater’s build and runaway emotions, she seems more troubled teen than burnt-out adult, but it’s vague and really it doesn’t matter. Complications ensue when Jiang meets and befriends a girl who works at the practice rink, Zhong Ling (played by newcomer Ding Xiangyaun), who skates on her own after hours. Zhong is everything Jiang is not and wishes she could be: free, confident, open to the world. But Wang notices her too, and when she takes Zhong on as a student, Jiang’s precarious psychological state becomes increasingly erratic.

Black Swan is the obvious point of comparison, but there are elements too of ‘90s psychological thrillers like Single White Female, Basic Instinct, and Perfect Blue, post-feminist films built around women competing with each other for personal and professional success. But where Darren Aronofsky in Black Swan pushes the horror elements of the scenario, emphasizing the grotesque effects ballet can have on the human body (and drawing a parallel between them and his heroine’s psychological contortions), Girl on Edge plays its drama relatively straight. Jiang Ning may fantasize and hallucinate, but director Zhou Jinghao grounds his film in the everyday realism of the sports film. Nothing too crazy happens in Girl on Edge: the parties are normal teen parties (albeit in an abandoned mall-turned-roller rink), the injuries, scrapes, and bruises are real but not ghastly, and the little indignities and cruelties of the mother-daughter/coach-athlete relationship are all too common. Zhou pays special attention to the skate sequences, which are uniformly excellent and filmed in a variety of interesting ways, all to maximize the beauty, difficulty, and impact of the skater’s movements, and just how precarious they are at all times, gliding on a knife along hard frozen water.

This means that while Girl on Edge takes the scenario of psychological horror, it actually plays like a sports drama. It’s outlandish elements are not so much an opportunity for shock or titillation as in Black Swan — this film’s equivalent of that film’s love scene finds the two women sharing a bed during a sleepover, scooching ever so slightly closer together while facing opposite directions under the covers — but instead function more as metaphor for the demented requirements of high achievement in any kind of youth sport. Girl on Edge’s world of figure skating resembles almost exactly the worlds of ballet and youth baseball that this writer’s kids are trying to manage, in their insane demands for time and energy, but also in the fact that much of the psychological pressure they inspire is wholly self-inflicted — one of the film’s slightest yet most affecting scenes comes when Jiang confronts a rival skater who she thinks has sabotaged her, only for the girl to respond that she came in next to last in her last tournament: she’s going to college and doesn’t care if she wins or loses, certainly not enough to mess with another competitor. It’s a cliché, but it’s true: an athlete never competes with another person; their greatest opponent is always themself.

As the requirements of the scenario unfold in the film’s final 20 minutes or so, Zhou isn’t content to simply rest on the revealed, but by no means unexpected, twists. Rather, he drives home this lesson and allows his heroine her moment of triumph. In these last scenes, Girl on Edge turns into a truly moving sports movie. It’s not just “Black Swan on ice.” It’s The Cutting Edge, but more alive and half as cruel. — SEAN GILMAN

Her Will Be Done

Julia Kowalski’s Her Will Be Done begins with a cryptic series of images; pitch-black night, a pile of discarded clothing, closeups of various faces, impassive & expressionless. A figure writhes around, engulfed in flames. The camera lingers on the visage of a young girl, then cuts to a shot of Nawojka (Maria Wróbel). It’s unclear if we’ve just seen a flashback or a particularly grim dream sequence, but something clearly haunts Nawojka. We proceed to follow several days of her life on the family farm; she’s surrounded by her stern, gruff father and two brothers, one as odious as the other. The eldest brother is on the cusp of marriage, a ceremony that will bring together most of the denizens of this small, rural French community. But Nawojka and her family are outsiders, Polish immigrants who have slowly but surely been integrated into the community, and their dour life is captured in a string of claustrophobic interiors and damp, muddy fields by cinematographer Simon Beaufils.

Kowalski is doing a few things here: creating a fully lived-in, mostly realistic milieu, and then slightly heightening the bad vibes until things begin to tilt over into horror territory. There’s nothing outright scary here, just an ominous mood and slowly encroaching dread. We gradually discern that the film’s opening scenes are of Nawojka’s mother dying, and that Nawojka now fears that the same evil that possessed her mother has been passed on to her. She prays fervently, endures episodes of night terrors, and is occasionally gripped by convulsing fits. Is it witchcraft? Or is this all in her head? And does the mysterious illness tearing through the cow herd have anything to do with it?

Into this simmering psychological landscape comes Sandra (Roxane Mesquida), a former resident who has returned to the village after a long absence to sell her recently deceased parent’s’ property. Sandra cuts a vibrant path through this sallow world; decked out in short shorts, dyed hair, and a leg brace that she makes no effort to hide, the woman awakens something in Nawojka — a sexual energy, yes, but also a sense of power, and a refusal to be cowed by the small-minded, hopelessly ignorant people of the village.

Kowalski is playing in fairly well-trod territory here; a young woman beaten down by a patriarchal society, afraid of her own sexual desires, society and witchcraft as metaphor for coming of age and free will, etc. This is standard folk horror territory, but it’s enlivened here by the filmmaker’s careful attention to detail, patiently establishing an emotionally grounded world before pulling the rug out from under the audience. Kowalski also has a real eye for composition and pacing, slowly turning the screws until tensions finally burst during a prolonged wedding celebration. A drunken midnight drive seems inspired in part by the nightmarish Wake in Fright, and ends in a similar fit of violence. The fearful, ignorant masses will always try to destroy what they can’t understand, and breaking free of that cycle is sometimes victory enough. Her Will Be Done is both tragic and triumphant, the two extremes inextricably tied together. Nawojka seems to succumb to a prescribed fate, before realizing that there is no fate but what you make. — DANIEL GORMAN

A Useful Ghost

One day, noticing an influx of dust into their apartment due to some construction outside, a person known only as an “academic ladyboy” (as they call themselves and are credited on IMDb) buys a new vacuum cleaner. It seems to work well, but that night the vacuum coughs out all of its dust. A call to the shop brings a repairman almost instantly, who informs them and us that the machine is probably haunted. In fact, the whole factory where it was built is haunted. He relates the story of one ghost, a vengeful spirit who died at work and takes control of the machinery there at inconvenient times, leading ultimately to the factory’s closure. But he also tells us a love story, one about the son of the factory owner whose wife (Nat) dies and comes to inhabit another, different vacuum cleaner. This ghost tries to be helpful.

The first story is rather brief, the kind of ghost story you expect: a person has been wronged and their spirit lingers out of an otherworldly need for vengeance. The factory closes and that appears to be the end of it. The second story is more unusual, romantic in that the dead wife loves her husband so much that she returns to him, albeit in altered form. He loves her just as much, which is where the difficulty comes in: for him, the vacuum is his wife; for the rest of the world, this guy appears to be hanging around, talking to, and making out with a common household appliance.

The metaphor here is obvious enough, about people learning to accept love in whatever form it happens to come, even if it seems absurd to them. But director Ratchapoom Boonbunchachoke is not interested in simple metaphors. Or rather, they’re interested in spinning this basic scenario (ghosts are real and can inhabit appliances and interact with people) in as many different metaphorical directions as possible, and then compound them by freely mixing their meanings and implications. The result is as dizzying as it is beguiling.

The romance takes up the bulk of the movie, as Nat is gradually more accepted and believed in by her husband’s family. She ultimately proves her worth by the fact that she can enter living people’s subconscious. It is asserted that a ghost is created in one of two ways: either the ghost can’t give up a living person, or a living person can’t give up the memory of the person who died. Nat’s husband’s family uses this power to find out which of their employees is attached to the ghost that’s been terrorizing the factory, then they solve the problem by forcing them to forget the person who died.

That first story then becomes a romance as well, as the worker who died has returned not for vengeance so much as because they are in love with another worker. What we thought was a simple story of neglect by management leading to the revenge of a worker from beyond the grave turns out to have been not the owner’s fault at all. However, the only way they discover that is by inflicting even worse abuse on the workers (drugging them all, invading their dreams, then erasing their memory via electroshock treatments).

Thus in its second half, the film turns from quirky romance into political polemic, as Nat’s ability is used not just by the factory owners, but, through a chance meeting with a government minister, eventually by the state itself. It seems the minister and his allies are plagued by ghosts as well, ghosts of all the activists and radicals they’ve murdered. Nat must choose whether to take their side, or that of her beloved and his family. And in the end, it all ties back into the mysterious repairman and the academic who hears his stories.

Comparisons to the worlds of Apichatpong Weerasethakul are probably inevitable, because his films are also populated by ghosts and spirits whose interactions with our world are treated as matters of fact. The first ghost, in possessing a giant air processor in the factory, seems to intentionally invoke memories of just such a device given a memorable zoom in Syndromes and a Century. But in truth, one’s mind wanders more to Wes Anderson when watching A Useful Ghost. Boonbunchachoke’s images are bright and colorful and carefully arranged, and he often shoots his speakers frontally, with them addressing the camera in closeups, rather than in standard conversational over-the-shoulder shots or Weerasethakul’s languorous long-shots. And the tone, whimsy hiding a dark, deeply pained and melancholic core, is more Anderson than it is Weerasethakul’s weary and wary wonderment. Boonbunchachoke uses a variety of techniques to evoke dream imagery, mostly adapted from the flaws of old film photography (scratches, flares, jagged cuts) which contrast with the plain, if colorful, digital reality, and the ghost possessions are visualized with charmingly simple special effects. And so, though the film seems at times dangerously close to becoming cute, ultimately it navigates deftly both the uncanny and the beautiful, finding the sadness in romance and the romance in righteous anger. — SEAN GILMAN

Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk

Iranian director Sepideh Farsi’s Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk seems likely to be the most important film to screen at the 2025 Cannes Film Festival. A personal document of life under Israeli siege and bombardment in Gaza, Farsi’s film peers into what life in Gaza is like in 2025 through the eyes of a single Palestinian woman, the 25-year-old Fatima Hassouna, a photographer and citizen journalist. Hassouna was killed by an Israeli missile strike that specifically and precisely targeted her family’s residential apartment on April 16, 2025. Ten other members of her family, including her pregnant sister, were also killed in the strike. The state-authorized family murder happened one day after Cannes selected the film for the parallel ACID program.

Hassouna might have had the brightest smile and biggest eyes in all of Gaza. As observed in Farsi’s film, she seemingly never stops smiling, even as the sounds of air raids and buildings falling distract the director, on the other end of a series of WhatsApp video calls. She is genuinely grateful for her life, and her infectious optimism seems like an impossibility in her position, though she doesn’t let Israeli injustices rob her of her humility and pursuit of happiness. Farsi asks about this too, pointing to the dissonance between the violence she describes — such as when she introduced us to an aunt whose head was found in a separate location from her body — and the beautiful and happy face that delivers the news to her. Hassouna loves to share her photos with Farsi over their video calls.

It’s difficult to identify any other regional cinema with as tilted a cinematic inclination toward documentary over fiction as the cinema of Palestine. Within this strong tradition of documentary filmmaking, a necessarily rich diversity of approaches persists. Farsi, an Iranian banned from her home country for her political films, has made films about Palestinians before, and is no stranger to filming beneath oppressive regimes. Her approach here involves three camera sources: the two screens Hassouna and her chat on, and a third camera to record the screens from an arm’s remove. The calls go in and out as Hassouna struggles to find consistent Internet access, pixelating and dropping at random. She could have chosen a more screen-life approach and actually used the material presented on her screen, but instead, she chose to record the video call bootleg style from another device at about an arm’s length away. It’s like a friend showing a photo on their phone, something that actually happens quite a bit in Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk: the observing friend can’t enter the world of the photo, but they do have a window into the lives of their friend. And that window mobilizes their capacity for empathy.

Carol Mansour’s Aida Returns from last year similarly exists at a stylistic remove between the digital and real worlds, emphasizing both the emotional closeness and real-world separation between those living in Palestine and caring observers who don’t. In that film, Mansour, unable to travel home to Palestine, records a series of video chats between two Lebanese friends (one of whom gets detained at the border) and herself as her friends return the ashes of Aida Abboud Mansour, Carol’s mother and a Nakba survivor, to Yafa, Palestine. The similar styles of Mansour and Farsi’s latest films highlight more than mere creative approaches to practical filmmaking problems; they point to the attempted isolation of Palestine from the rest of the world while still balancing a calling to catalyze empathy. Without the empathetic voyeurism of the way the calls are presented to us, the stakes of this balance would be jeopardized.

A long and deafening week after Hassouna’s death, Cannes released a statement that broadly condemned violence while also removing any perpetrators of violence from the responsibility of having ended her life. They do not use the word “Israel” anywhere in their statement that mourns her death. A more morally appropriate response came from the more than 750 signatories of “artists and cultural players” who signed a statement to “refuse to let our art be an accomplice to the worst” and to use cinema to carry the messages of those who die in indifference. Petitions, of course, are meaningless without action — but hopefully these filmmakers follow up on their statement to create art that pushes against the divisive agendas of the pro-colonial far-right and neoliberal. The art these filmmakers make in response will be, in some way, an extension and reflection of Hassouna’s legacy. — JOSHUA POLANSKI

Comments are closed.