Natchez

Director Suzannah Herbert’s documentary Natchez, which counts Sam Pollard among its executive producers and won this year’s Documentary Competition at the Tribeca Film Festival, captures the contradictions and tensions of a small Mississippi town reliant on Antebellum tourism with polyphonic complexity. Its implications broaden as its focus grows ever more specific, and in Herbert’s humanistic yet uncompromising direction, Natchez emerges as a microcosm of how the violent white supremacy embedded in the founding of the United States continues to infect the present.

Director of photography Noah Collier captures Natchez, the documentary’s setting and subject, with a hazy, sunbaked glow — which, in its subtle contrast with Herbert’s rigorous, near-anthropological approach, echoes one of the film’s main thematic threads in its very form: the tourism economy of Natchez has long presented the historic town as a beautiful escape from the harsh present, a seductive and lucrative dream that encourages people to look away from its more complicated, often brutal past. Natchez, pre-Civil War, was a hub for the cotton industry and had the most millionaires per capita in the United States. Throughout the 20th century, with diminished wealth but an array of well-appointed historical mansions, Natchez re-oriented its economy toward tourism, with its prominent Garden Club giving tours on twice-yearly “pilgrimages” that emphasize the luxury and beauty of wealthy Antebellum lifestyles, while papering over the economy of human trafficking and forced labor that propped it up.

Herbert, filming in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic and the 2020 mass protests for racial justice, finds Natchez at an economic and cultural crossroads: tourism is diminished, with millennials and Gen Z uninterested in revisionist Antebellum history, and the town’s Black community and the National Park Service are in the midst of a long, frustrating process to change the local narrative of history to more meaningfully incorporate the facts of slavery — even as the Garden Club tour guides, mostly women who lead their tours in full hoopskirts, seem more interested in continuing to highlight the mansions’ beautiful furnishings and inaccurately describe slaves as “servants.”

Herbert follows numerous subjects from Natchez to paint a complex community portrait. Perhaps the most prominently featured is Tracy “Rev” Collins, a Black pastor from a neighboring county who gives tours of Natchez that emphasize the history of slavery. Herbert presents a generous amount of footage from these tours, and the charismatic and erudite Rev — with his accuracy and rigor in delineating the histories of slavery, reconstruction, and Jim Crow in Natchez — becomes our de facto tour guide as well. National Park Service rangers and Deborah Cosey, the first African American member of the Garden Club who gives tours of the former slave quarters she lives in, are also highlighted as effective stewards for the experiences of enslaved people in Natchez. The white Garden Club members’ mansion tours are given plenty of screen time as well, but Herbert homes in most on the inaccuracies and elisions of their tours, some of which tip into blatant racism. Herbert and editor Pablo Proenza effectively use montages of repeated phrases and themes between tours to emphasize the common false narratives perpetuated among the traditional Garden Club tours, and they also frequently juxtapose these revisionist presentations against the direct honesty of tour guides like Collins and Cosey.

Herbert takes care to capture the town and its residents accurately and with all their attendant complexities. Natchez cannot be simply boiled down to a backward-looking town that needs to adapt or die; it is referred to repeatedly as a “blue dot” in a red state, and it was the first town in Mississippi to elect an openly gay mayor. The town’s current mayor, Dan Gibson, is portrayed as a unifying, forward-looking civic leader — a key scene shows him presenting Cosey with a key to the city — yet the obviously more conservative Garden Club is a cultural and economic power center.

In a culminating sequence late in the film, Herbert captures the contradictions inherent in Natchez’s white population, specifically, to startling effect. Tracy McCartney, a white Garden Club member who has recently divorced her wealthy husband, takes Rev’s tour, and is empathetic and attentive to his stories about the brutality of the slave trade in Natchez. Herbert intersperses this scene with David Garner, a prominent figure of the local gay society who has lately been struggling to give tours of his home due to Parkinson’s disease, delivering an unprompted racist tirade directly to camera. Herbert has portrayed these two subjects as largely sympathetic, though ambiguous, figures up to this point, and her ultimate juxtaposition of them is coldly revealing: In pushing past the pleasant veneer of revisionist history accepted by the white population for generations, one might find in any individual either a reasonable willingness to learn the truth, or unbridled, hateful racial animus.

The question that ultimately lingers at Natchez’s conclusion is whether the white arbiters of Natchez’s cultural heritage will accept the factual history — and still-lingering problems — of their town, or content themselves to continue retreating into the fanciful, morally corrosive fictions they were raised on and have profited from, despite the largely Black community members’ efforts to preserve and commemorate their town’s full history. This question, of course, is as relevant nationally as it is locally, particularly in the protracted period of racist backlash American society is currently festering in. In her probing and critical, yet invariably empathetic, interrogation of this tension in the unsettled community of Natchez, Herbert has crafted a major achievement in documentary filmmaking. — ROBERT STINNER

Married directorial pair Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani have consistently risked being hit by the type of criticism that considers “postmodernism” a dirty word. Many a contemporary arthouse filmmaker likes to riff on the tropes and stylistic sensibility of the disreputable but distinctive film genres, and they are hardly the first filmmakers to pay homage to Giallo horror, sexploitation, and chintzy spy movies. What sets them apart is not having much interest in simply striking the poses and allowing the viewer’s knowledge of the references to poke gently at nostalgic spots. The real B-movies of this kind always had a little bit of weirdness to their edits and compositions, or an excess to their framings and colorings, and the Cattet/Forzani style tends to use these for a form of stylistic extremity. The rhythms are skittery and staccato, with attention-grabbing edits to make the garish framings feel like riding a bumper car. With Reflection in a Dead Diamond, they’ve delved deeper into their bag of tricks than they ever have before and come up with both their finest film to date, and something like the ultimate postscript to James Bond and the spy movie as a whole.

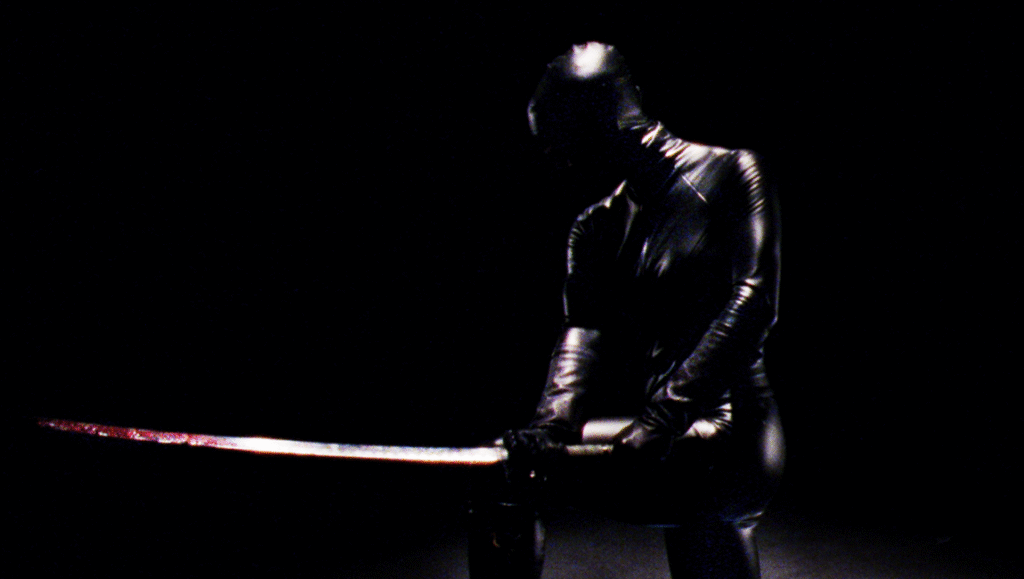

Summarizing what happens in Reflection will be beyond the abilities of most reviewers, and possibly the creative team’s: even the most skeptical would have to concede that its use of montage is closer to experimental film techniques than most narrative films. It starts off as something about a 70-year-old spy in a white suit (Fabio Testi) at a luxury hotel by the Côte d’Azur who’s obsessed with a woman also staying at the hotel. But once we start flashing back to his younger self (Yannick Renier) and his involvement with the mysterious leather-suited Serpentik, the film becomes profoundly disinterested in making itself clear and turns into a whirlwind of gaudy transitions and untraceable shifts in power dynamics. It’s like a Spy vs. Spy cartoon with real people, particularly the ones where the female Grey Spy triumphs over the two men.

Some of the creative choices in Reflection are easier to approximate, such as the two most memorable outfits being Serpentik’s highly feminine and highly deadly fetish-adjacent gear, and a metallic dress whose mirrors serve as cameras: catnip to any filmmakers enamored with cutting loose formally with reflections and playbacks. There’s also comic book panels, plenty of meta-cinema, enough latex masks for eight more Mission Impossible films, and ridiculous props like a bullet-shaped lipstick. Descriptions of certain formal choices and stagings would likely defy description, but the recurring use of hotel carpeting patterns to mark transitions recalls Scott Stark’s great Hotel Cartograph, and certain sequences suggest what could have happened if avant-garde filmmakers like Paul Sharits were fully embraced by popular cinema. The titular diamonds get used for everything from mise en scène glitter, to sharp-edged weaponry, to op art-influenced graphics in a way that allows the film to pay tribute to the James Bond opening credits sequences in its own nutty fashion. One fight scene even turns the need to obscure particular elements of violent scenes into a sort of Brechtian joke about how blatantly obvious these types of cuts and framings can be in most movies.

“What does it all mean?” largely comes down to how seriously you take it. The two most notable film influences cited by the directors are Mario Bava’s colorful ’60s campfest Danger: Diabolik and Monte Hellman’s late period digital ramble Road to Nowhere, which also stars Testi. The latter film being heavily focused on deconstructing Vertigo might serve as the key for how Cattet and Forzani combined these two influences: the spy who usually saves the day in a self-consciously ridiculous fashion is now chasing a woman who he doesn’t even recognize anymore, she’s largely stringing him along, and the means of cinema will shape his downfall. It’s a playful reconfiguration of the so-called magic of the movies: you still wind up absorbing the spirit via osmosis of the old tricks, but it’s as upside-down and mirrored as the titular visual. — ANDREW REICHEL

Predator: Killer of Killers

Without raising too much of a film culture racket, the Predator films have endured for nearly four decades, steadily turning out a new entry every few years to keep the brand name alive. The persistence is commendable, but the results run the gamut from spectacular to abysmal, with the highest of highs going back to 1987’s The Predator, a meathead masterpiece with a genuine stake to the claim of greatest American action film ever made. The lows, meanwhile, include an ill-advised crossover with the Alien saga and, more recently, 2018’s The Predator, an exceptionally idiotic sequel that nearly killed off the franchise outright. Breathing new life and restoring focus to the series was 2022’s Prey, which pit the iconic Yautja beast against a fierce Comanche warrior in 18th century America. Directed by Dan Trachtenberg, Prey was met with quite this positive reception, despite not having been granted a proper theatrical release and left to compete for its audience amidst the glut of streaming content. That film was crucial in getting Trachtenberg the gig to return to the live-action Predator world with Predator: Badlands, due in cinemas this fall, but in the meantime he’s released Predator: Killer of Killers, an adult animated anthology film that explores the violent history of the Predator species. And while far from the best the Predator franchise has to offer, Killer of Killers does at least make for an entertaining amuse-bouche, spinning three tales of honor and survival that are jam-packed with stylish animation and plentiful servings of ultra-violence.

The first story is set in Scandinavia, 841 A.D., charting a Viking expedition out to eradicate an enemy clan. The leader of the pack is the ferocious Ursa (Lindsay LaVanchy), a vengeful Valkyrie who has brought along young son Anders (Damien Haas) in the hopes of molding a warrior out of him yet, forcing the boy headfirst into battle to gain firsthand experience in combat. As Ursa and company home in on their target, an invisible menace observes from the periphery, waiting for its moment to strike. Admittedly, the animation style for Killer of Killers takes some time getting used to, as the 3D-rendered characters are designed to emulate live-action movements, at least during the more dramaturgically pressing sequences. It’s a baffling design choice that recalls the worst of the Into the Spider-verse series, reducing any non-skirmish sequence into a soporific eyesore. Thankfully, matters do improve once the action heats up, allowing Trachtenberg and co-director Joshua Wassung — working from a script by Micho Robert Rutare — to kick things into high gear, first charting the might of Ursa as she rampages through an enemy Viking village, before setting her to square off against a Grendel Predator. Given its subtitle Killer of Killers, perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising that beheadings, bisections, and limb removals prove to be in ample supply, with Trachtenberg and co. relishing every moment to spill blood on screen, ending the first section on a high note.

This momentum carries on into the film’s middle section, which shifts the action to feudal Japan. Two brothers, Kenji and Kiyoshi (both voiced by Louis Ozawa), fight for the honor of becoming successor to their samurai warlord father, with Kiyoshi emerging victorious as Kenji flees the kingdom. Years later, Kenji returns as a ninja to confront his brother, though the reunion is cut short with the emergence of another Predator, forcing the skilled swordsman to take on an unfamiliar foe armed with futuristic technology. This section serves as the highlight of Killer of Killers, delivering a longer confrontation between Yautja and samurai that was only teased in 2010’s Predators. It also highlights the limitations of Trachtenberg’s concept, as any time spent watching Killer of Killers eventually gives rise to memories of the Spike TV series Deadliest Warrior, which likewise explored history’s greatest fighters and squared them off against each other in staged deathmatches. Here, that conceit remains fully intact. What would it be like to see a Predator fight against a Viking? A samurai? A ninja? What about a Naval fighter pilot?

Cut to act three, which nearly drops the ball completely. Moving on to World War II, our hero here is an American mechanic named Johnny Torres (Rick Gonzalez), who is drafted into the U.S. Navy and stationed in North Africa. When a Predator spaceship appears, Johnny takes to the skies with a Wildcat aircraft to fight off the invader. Killer of Killer‘s Ursa and Kenji segments benefit from centering strong, silent-type protagonists, letting the action do the heavy lifting and shading in the story. But in the film’s third segment, Johnny is realized as an irritatingly loquacious character, one who also he spends much of the aerial combat sequences hanging off the wing of his plane as he frantically tries to repair it — a feat that would have been more impressive had we not just seen Tom Cruise do this exact same stunt for real in last month’s Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning. But things don’t end at the conclusion of the third story, with Trachtenberg instead serving up a battle royale as an extended epilogue, even hinting at potential sequel territory with this project. By the time that tease occasions the screen, Predator: Killer of Killers has nearly run out of gas, despite clocking in a relatively concise 85 minutes. The final result slots in somewhere in the middle of the franchise’s spectrum of quality: it’s a not infrequently fun and diverting exercise, one where blood-soaked violence certainly is aplenty, but Trachtenberg and Wassung don’t leave the audience with much of anything lasting to chew on. Probably best to just look forward to Badlands. — JAKE TROPILA

Comments are closed.