“This language of the unreal, this fictive language which delivers us to fiction, comes from silence and returns to silence.” – Maurice Blanchot, The Space of Literature

“Force, presence, shape, they were all only words and none of them mattered. It wore many masks, but it was all one.” – Stephen King, The Shining

Gothic cinema inherits an ongoing obsession with writers and writing from its literary ancestors, but how does it translate such text-based fixations into its own audiovisual grammar? How does it stage “objective” diegeses in concert with the innately subjective representations of writers and the act of writing? This article approaches these questions, not by offering a comprehensive history of Gothic films depicting writers (that would require a long, book-length project), but by analyzing a trio of writer-focused Gothic films notable for their dealings with literary ancestry through negotiations between subjective interiority and diegetic objectivity.

Gothic literature shows up often as an object of study in film and television, with Gothic writers populating documentaries, biopics, and historical reenactments. Ken Russell’s pointedly titled Gothic (1986) gaudily dramatizes the mythic summer of 1816 at the Villa Diodati, where Mary and Percy Bysshe Shelley exchanged ghost stories with Lord Byron, John Polidori, and Claire Clairmont, and most importantly where Mary Shelley conceived of Frankenstein (1818). Mary Shelley is also the subject of the biopic Mary Shelley (2017), and the scripted drama Shirley (2020) centers on Shirley Jackson. Fictional versions of Edgar Allan Poe appear in Antonio Margheriti’s Danza Macabre (1964), Francis Ford Coppola’s experimental drama Twixt (2011), and James McTeigue’s schlocky horror-mystery The Raven (2012). Many documentaries study individual Gothic and Gothic-adjacent writers and texts (consider, for example, Stephen King: Shining in the Dark [1999], Bram Stoker’s Dracula: A Documentary [2007], Lovecraft: Fear of the Unknown [2008], and Edgar A. Poe: Buried Alive [2017]).

These “nonfictional” films and series adopt Gothic literature’s reflexive fixations, on haunted recordings and transcriptions, tormented authors and cursed manuscripts. Early Gothic literature constantly pores over its own written objecthood, from Horace Walpole’s foundational “found document” novel The Castle of Otranto (1764), to protagonist Emily’s poetic aspirations in Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), to the epistolary devices of seminal early-nineteenth-century works like Frankenstein (1818), Melmoth the Wanderer (1820), and The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824). Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick notes in The Coherence of Gothic Conventions (1986) that Gothic texts are often characterized by “tales within tales, changes of narrators, and such framing devices as found manuscripts or interpolated histories.” Relatedly, in New England’s Gothic Literature (1995), Faye Ringel asserts that the very “emblem of the Gothic is the hidden text: the lost manuscript, the missing will, the madman’s ravings.”

American Gothic cinema advances these themes in its own regional contexts, from the Hollywood screenwriter protagonist of Voodoo Man (1944) to the godlike New England horror author Sutter Cane of In the Mouth of Madness (1994). This national trend also stems from a literary lineage: the American Gothic expands on its British ancestry, with epistolary elements in Charles Brockden Brown’s foundational novels Wieland (1798) and Edgar Huntly (1799), and in Edgar Allan Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838). Shirley Jackson’s Hangsaman (1951) centers on a trauma-stricken young writer, and The Bird’s Nest (1954) also advances an interest in textuality and transcription. Psychically fractured writers populate much of Stephen King’s expansive oeuvre (among many other novels and stories, consider The Shining [1977], Misery [1987], and Bag of Bones [1998]). Joyce Carol Oates pays reflexive homage to King’s writerly fixations in Jack of Spades (2015), and King’s friend and collaborator Peter Straub engages with metafictional representations of writing in his Timothy Underhill sequence (Koko [1988], Mystery [1990], The Throat [1993], lost boy lost girl [2003], and In the Night Room [2004]).

Kristopher Woofter’s 2023 essay, “Actuality in the Shadows: F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu, Pseudodocumentary, and Mockumentary Aesthetics,” detects an evolution of literary impulses in Gothic horror cinema from its inception. Woofter notes that “early silent cinema was received not with naïve shock, but dialogically: a sensational combination of actuality and illusion where exploitation, manipulation and documentation of reality were always in/at play.” Woofter’s observation recalls negotiations of “reality” in the fraudulent authorship of “found document” novels like Otranto and Arthur Gordon Pym. Woofter turns to F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922) (an unofficial adaptation of Stoker’s Dracula) to identify an evolving interest in recording technology from literature to cinema. Woofter writes that, as “Bram Stoker’s 1897 source novel did with modern communication inventions such as sound recording and typing, Murnau’s film both references and builds its narrative upon new communication technologies. Glass, frames and screens were the materials of cinematic projection technology.” How, then, do Gothic cinematic metafictions expand on this rich lineage?

James Kenelm Clarke’s Exposé (1976) offers an interesting entry point into the tradition of writer-centric Gothic cinema. It follows a writer named Paul Martin (Udo Kier), who retreats to a secluded cottage to complete his second novel. It is in many ways a crude and lurid exploitation film, narratively and ideologically dubious, but it exemplifies the imbrications between literary and cinematic Gothic recordings. Clarke directs the film with a feverishly libidinal charge, braiding creativity with Freudian sublimation while also testing the division between writer subject and written object, both formally and thematically. The camera roves, hovers, and leers, a restless participant in the entanglements of recording.

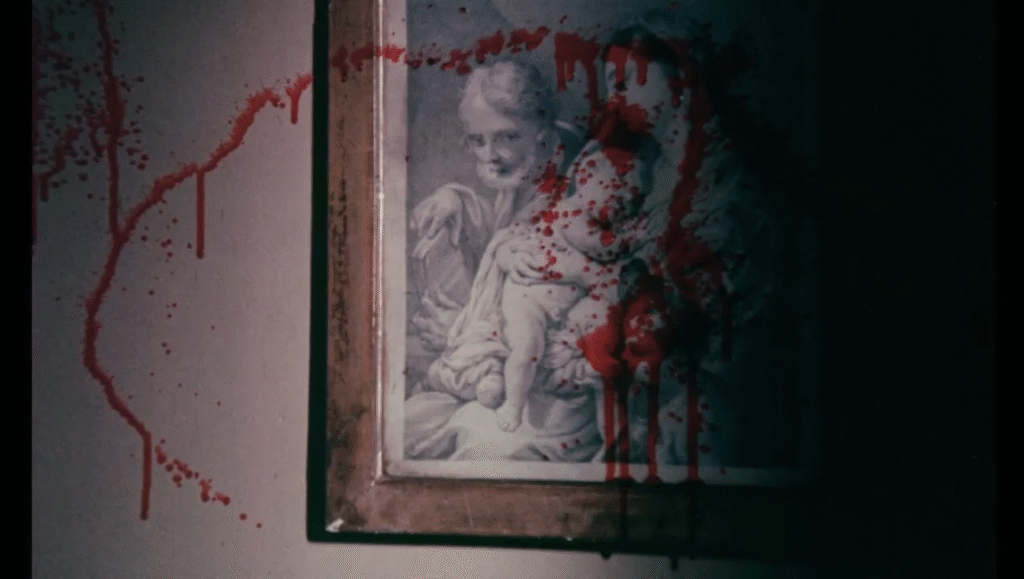

An early montage represents Paul’s psyche while he’s having sex. The sequence submerges us in Paul’s disturbing subjective visions, which build in tandem with the “objective” coital act. The hallucinatory episode concludes by rupturing the divide between subject and object, pleasure and pain: blood drips onto a manuscript’s title page before spattering onto Paul’s screaming face. Later, Paul recites his novel aloud for his secretary Linda (Linda Hayden) to transcribe. This is a scene of pure cinematic Gothic, the filmed act of writing: narrative materializing within narrative “in real time.” This episode also advances the film’s overarching interest in creativity as libidinal sublimation; a relentless lasciviousness permeates Paul and Linda’s blurry relationship, in which they enact various games of psychosexual deception that escalate into a finale of hurried, anticlimactic revelation and violence. The hastily explained resolution shows Paul to be a literary thief and impostor, one in a long line of Gothic frauds.

Stephen King has often engaged with some of Exposé’s key themes, generally to more sophisticated ends. Many filmmakers have adapted the author’s writer-centered novels for the big and small screens, from Tobe Hooper’s Salem’s Lot (1979) and George A. Romero’s The Dark Half (1993) to David Koepp’s Secret Window (2004) and Pablo Larraín’s Lisey’s Story (2021). Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980) might be the most overtly cinematic representation of King’s career-long obsession with writers and writing, in that it deliberately evades literary interiority for the purpose of meaning-laden film semiotics. Kubrick’s adaptation strips away the novel’s rich backstory and characterizations, retaining the general narrative shape but significantly changing the final act. In the film, struggling writer and recovering alcoholic Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) is hired to serve as caretaker for the uninhabited Colorado Overlook Hotel during the winter. He brings his wife, Wendy (Shelley Duvall) and his clairvoyant son, Danny (Jake Lloyd), along for the seasonal appointment. Kubrick’s direction and Nicholson’s dark kabuki performance render Torrance menacing from the outset; the hotel’s supernatural energies and inhabitants seem only to nudge him toward violence he already intends.

In Kubrick’s cinema, characters typically read not as conscious beings so much as metonyms of cultural signification. Nowhere is this made clearer than in the director’s depiction of Jack Torrance as a leering patriarchal symbol, his thinly veiled corrosive masculinity hiding behind a flimsy “tortured writer” façade. The film’s writing sequences are pure performance: Torrance framed in an operatically vast hall, his chattering keyboard as frenzied as the choral Krzysztof Penderecki compositions that soundtrack his rapid breakdown. His wife Wendy’s secret discovery of his “manuscript” (a sort of madman’s concrete poetics, consisting of one repeated and restructured utterance (All work and no play make Jack a dull boy) betray the horror of the film’s semiotic obsessions: signifiers with nothing to signify, a void of meaning.

Kubrick’s adaptation is less faithful to its source material than Mick Garris’ underrated, King-penned 1997 miniseries. Nevertheless, Kubrick’s film successfully expresses King’s American Gothic obsessions (the 1977 novel is replete with references to Walpole, Poe, and Jackson). In Herman Melville’s seminal American Gothic novel, Moby Dick, the monomaniacal Captain Ahab proclaims that “All visible objects, man, are but as pasteboard masks,” a phrase Douglas E. Winter invokes in his essay “The Night Journeys of Stephen King”; Winter identifies the specter of Ahab’s revelation in King’s work, arguing that “horror fiction is an intrinsically subversive art, which seeks the face of reality by striking through the pasteboard masks of appearance.” Kubrick’s film follows in kind, slashing past illusive signifiers to expose the abyss beneath, archetypal images of horror gesturing to that which resists representation: an endless snow-crusted hedge labyrinth, seething waves of blood, faces contorted by madness, written language reduced to a cry of absence.

Like Exposé and The Shining, Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Loft (2005) depicts a creatively blocked writer retreating to a remote location. The film follows prize-winning literary novelist Reiko Haruna (Miki Nakatani), who is writing a romance book at her editor Koichi Kijima’s (Hidetoshi Nishijima) insistence. To help speed up Reiko’s process, Koichi recommends a spacious, isolated house where Reiko can focus, which happens to be situated next to an ominously decrepit archaeological research site. Reiko’s neighbor, Makoto Yoshioka, uses this site to study a recently uncovered mummy. The mummy becomes an object of increasing mystery, its identity ambiguated by the spectral emergence of a murdered woman discovered in the same area.

Loft recalls Exposé and The Shining in its approach to perspective. Exposé mostly follows its hack writer protagonist, but it also devotes some scenes to its deceptive secretary’s point of view. The Shining alternates between various perspectives: not only Jack, Wendy, and Danny Torrance, but also the Overlook’s clairvoyant head chef, Dick Hallorann. Loft is more complex than either film in its subjective representation: it is a film of psychic fractals, whose central Gothic mystery is amplified by cryptic shifts between the memories, visions, and nightmares of writer Reiko and archaeologist Makoto, which continually blur the distinction between present and past.

Loft’s mummy becomes an amorphous symbol of that most constant of Gothic symbols, the Return of the Repressed. The mummy might not only be an ancient woman’s preserved body, or the conduit for a more recently murdered woman’s revenant spirit; the mummy might also somehow possess the minds and bodies of both Reiko and Makoto. Throughout the film, Reiko inexplicably vomits ectoplasm-like geysers of black sludge, later learning that the mummified woman ingested mud as an unconventional anti-aging strategy. Relatedly, in a cryptic confession of murder, Makoto says of the mummy, or the revenant spirit, or both: “She slipped right inside me, in some inexplicable way. And then … I began to feel I’d made a terrible mistake about human life and death. In an instant, she shattered my convictions as a scientist. I felt as though a thousand years of time were rushing in. In the end, she said she would take me to hell.”

As the film’s mazelike mystery swallows Reiko’s attention, her writing project fades into the background. Reiko’s coworker introduces her to an educational documentary filmmaker, who possesses mysterious, early 1920s footage labeled Midori Swamp Mummy. Loft unravels a Gothic lineage of obsession with recording when the author, Reiko, sits in a dark screening room to watch flickering black-and-white timelapse footage of the shrouded mummy. The haunting figure of Reiko’s subjective horror — of her nightmares and her sickly hallucinations — is rendered an object of cinematic representation, perspective and reality enmeshed in the metaphoric dream-space of the screening theater.

This trifecta of films — Exposé, The Shining, and Loft — represents a long, rich tradition in Gothic cinema: filmed negotiations with the writer, the writing act, and the written object. There are plenty of openings here for further study. Consider seminal writer-focused horror films like To the Devil a Daughter (1976), I Spit on Your Grave (1978), and House (1985), or Dario Argento’s author Giallo diptych The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970) and Tenebre (1982), or countless additional Stephen King adaptations. The Gothic is a mode defined by layers of transcription, by the very act of documentation; in writer-centered Gothic cinema, these layers endlessly haunt and possess. Gothic lenses can appear as disturbing mirror reflections, or as windows into abysses where meaning is endlessly deferred or destroyed.

Comments are closed.