The purest, and arguably most puerile, definition of auteurism necessitates a neat classification of artistic idiosyncrasies. The governing principle behind this approach is to find commonalities between an artist’s not-so-varied work in the hopes of making a magical discovery about the one big meaning behind it all. However, even for a filmmaker like, say, Wes Anderson, whose projects have increasingly been accused of forming some matryoshka doll-like filmography of replicas, this definition of auteurism feels too insultingly narrow. For it undermines the idiosyncrasies — dare one say, incongruities — that ought to exist across every great artist’s output. Wes Anderson hasn’t endured as Wes Anderson just because he has replicated his fussily overstylized mise en scène and symmetrical framing, then; it’s because he has tinkered around with it — hell, even deconstructed his entire visual edifice in Asteroid City, and, to an even greater extent, in his 39-minute short, The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar (2023).

The other great Anderson of our times — sorry, Paul W.S. fans — has always resisted this overly simplistic auteurist classification. Paul Thomas Anderson’s filmography — up until, but not including There Will Be Blood (2007) — is characterized by the sort of aggressive stylization that turns emotional dramas into action films: the camera, like the characters in his ’90s films, is almost exhaustively restless, constantly desperate to whoosh in and capture all the emotion felt and expressed by his characters to doubly and triply amplify its emotional intensity. There’s no subtlety to spare here: everything and everyone seems to be on the verge of exploding (pun intended), and PTA is most concerned with conveying that through his visibly dynamic filmmaking. But everything that comes after TWWB, especially post-The Master (2012), is almost uncharacteristically elegant. Sure, Jonny Greenwood’s splendidly clinking and clanging soundtracks are direct substitutes for Jon Brion’s jangly background scores that gave PTA’s earlier work its jagged rhythm. But the camerawork and character work are also remarkably different, most notably for their restraint; there’s an assured confidence — seemingly lacking in PTA’s earlier work — that the audience will get what he wants to say without him having to insist upon it. Is this change in approach simply because the period settings in films like Phantom Thread (2017) force Anderson’s hand with regard to exercising more restraint? Or is it that the director has found a calming “cure” — in the form of the most delectable and carefully selected poisoned mushrooms — to the cocaine-fueled emotional highs and lows constantly propelling his emotional magnum opus, Magnolia (1999)?

It’s hard to say anything definitively. And that’s very much part of PTA’s enduring appeal. Rewatching Magnolia after rewatching Phantom Thread leaves you with all kinds of mixed feelings that, really, is what makes auteurism valuable: is restraint always better than grandiosity, or is it simply a matter of personal preference? Would Magnolia work better had PTA directed it with the same measured precision he exercised in directing Phantom Thread? Would it not lose a lot of the brashly expressive emotional vulnerability that proves the defining feature of Magnolia? And what exactly will it gain in return?

There, again, is simply no definite answer to this — only, it seems, a matter of preference. Because, despite often feeling like Anderson’s most forcefully constructed film about coincidental connections, Magnolia is, in some odd way, also Anderson’s freest work. It was made after the critical and commercial success of Boogie Nights, when Michael De Luca, the head of production at New Line Cinema, essentially gave the director carte blanche to make whatever he wanted. And so what we see in Magnolia — to date, the director’s longest film — is a little bit of everything PTA wanted to say about people living in the San Fernando Valley in the ’90s, all unified by this grand idea that humans — despite their differences in age, race, gender, class and sexuality — are innately connected by their suffering — in particular, their drug, daddy, and death issues. It’s a naively optimistic notion carried out with such vigorous conviction that part of you — even, like this writer, at the getting-very-grumpy age of 29 — wants to believe in it as a universal truth.

And you do, for a considerable while, because Anderson vehemently refuses to play by the rulebook. The film opens with what can only be described as an ancillary prologue, whereby an omniscient narrator (voiceover coming courtesy of Ricky Jay, who also stars in the film as the producer of a reality television show, What Do Kids Know) flatly recounts three bizarre stories about coincidence that betray logical sense but did, in fact, happen. Then, almost abruptly, the film breaks into a musical montage sequence, introducing you to all six characters we are going to encounter throughout the movie. You’d expect to see the credits appear throughout this five-minute-long sequence, briefly giving you a quick glimpse into each of these broken characters’ lives. But no — you’re thrown right into their lives, spliced together by a series of match-cuts that hint at the potential connections between them without ever clearly revealing them to you. Magnolia maintains this mystery, and — most importantly — relentlessly propulsive energy throughout its first act (Anderson, rather perfunctorily, divides the film into three parts, each “act” marked weather conditions), wherein every choreographed whip pan and dolly-in slaps you into a state of dazed submission to a filmic form this committed to turning people’s emotional problems into viscerally experiential cinema.

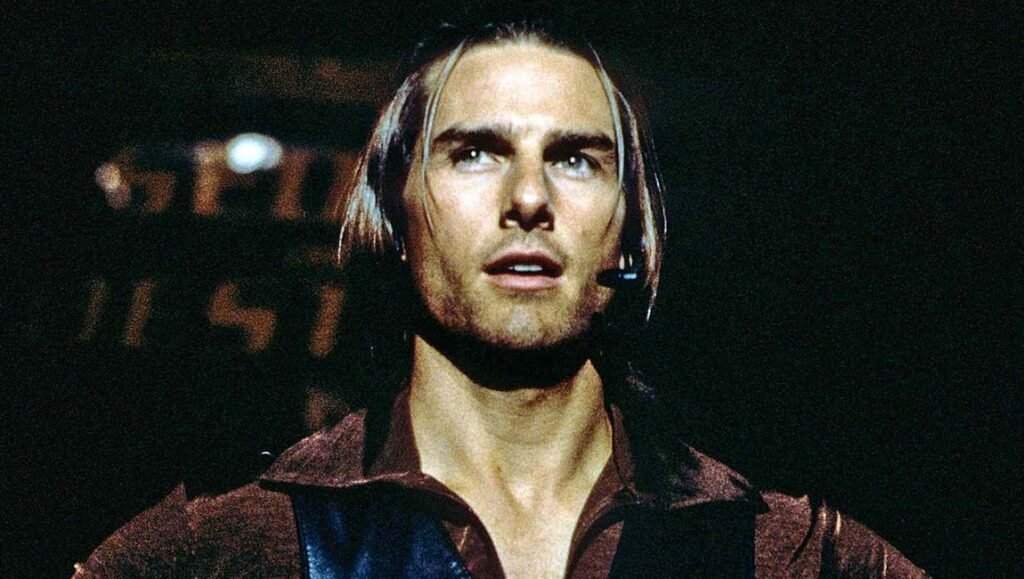

Once the exhilaration begins to wear off, however, a sense of exhaustion begins to settle in. It’s not because Magnolia’s mosaic of narratives takes a drastic turn for the worse, but because Anderson’s filmmaking continues to be the same: recklessly moving between its myriad of narratives, when, in fact, it probably could accomplish the same ends even if handled less aggressively. The film’s second act — marked by the chapter title “Light Shower. 99% Humidity. Winds SE 12 MPH” — features some terrific performative cockiness (Tom Cruise, playing the vilest character he ever has in his career) and melodramatic freakouts (Julianne Moore’s highly strung-out breakdown at a pharmacy remains absurdly astonishing). But it also comes across — not just in Magnolia, but, generally, in this kind of network narrative film — as little more than a highlight reel for its actors. PTA somewhat justifies this performative volume by throwing his characters into high-pressure emotional situations — an interviewer is gradually breaking down Cruise’s messianic façade as he promotes his misogynist book, Seduce and Destroy; Moore’s world is rapidly falling apart after realizing that she actually loves the dying man (revealed to be the same person responsible for Cruise’s character’s daddy issues) whom she thought she only married for the money and has cheated on multiple times. Still, it feels like the director’s skipping over — or, rather, cutting away from — seeing their worlds collapsing to showing you the Oscar-nomination clip reel outburst that comes after it.

This unnaturally operatic emotionality, however, is not a problem in and of itself if the actors and makers are wholeheartedly committed to it. And while there’s no questioning PTA’s (or any of his actors’) artistic integrity or intentionality, Magnolia’s hyper-emotionality also feels unnaturally strained, almost as if PTA is trying much too hard to make you buy into his world of melodramatic coincidence. Close-up shots of prophetic messages (“but it did happen”), repeatedly spouted declarative dialogue between characters (“we might be through with the past, but the past ain’t through with us”), and, perhaps most egregiously, genius quiz-show kid, Stanley Spector (Jeremy Blackman), breaking the fourth-wall to tell us raining frogs is “something that [regularly?] happens” all makes you want to ask PTA if he does, in fact, believe any of this. Because anyone else, who’s not a persnickety realist or just has conveniently skipped or ignored the opening five minutes of your film, would, given that you’ve convincingly set up a film about magical chances and coincidence. The constant nudging and prodding only takes you out of the film, making you further question PTA’s flamboyant cinematographic and editing choices as a sort of glossy cover-up for a movie whose material he doesn’t truly believe in.

Which shouldn’t be the case because Magnolia, despite Anderson’s over-eager attempts at profundity, still feels remarkably sincere. The emotional vulnerability conveyed by an otherwise confident game-show host (played terrifically by Philip Baker Hall) through his fumbling words finds its echoes in the swearier, yet still genuinely heartfelt, interaction his show’s former producer (Jason Robards) has with his nurse. That very nurse’s genuine kindness (Philip Seymour Hoffman, turning in his customary low-key scene-stealing performance) extends to the sweetest male character in all of PTA’s films, rookie cop Jim Kurring (an incredibly likable John C. Reilly), who begins a totally honest, no pretense-and-pretend relationship with an otherwise all-pretense-and-pretend girl (Melora Walters), suffering as much from daddy issues as she is from drug addiction. These people and the connections between them — literal and/or emotional — are all deeply felt, with PTA using the luxury of that 189-minute runtime to provide us with scenes that not only force us to see all of them freak out, but also gradually settle down. It’s enough to make one wonder if the PTA who made Phantom Thread would iron out all these excesses now, stitching something altogether more elegant out of Magnolia. But another part of you knows this thought exercise is pointless: Magnolia’s moments of elegance wouldn’t exist without its exasperating (and exhilarating) emotional directness — and frogs bless PTA for that!

Comments are closed.