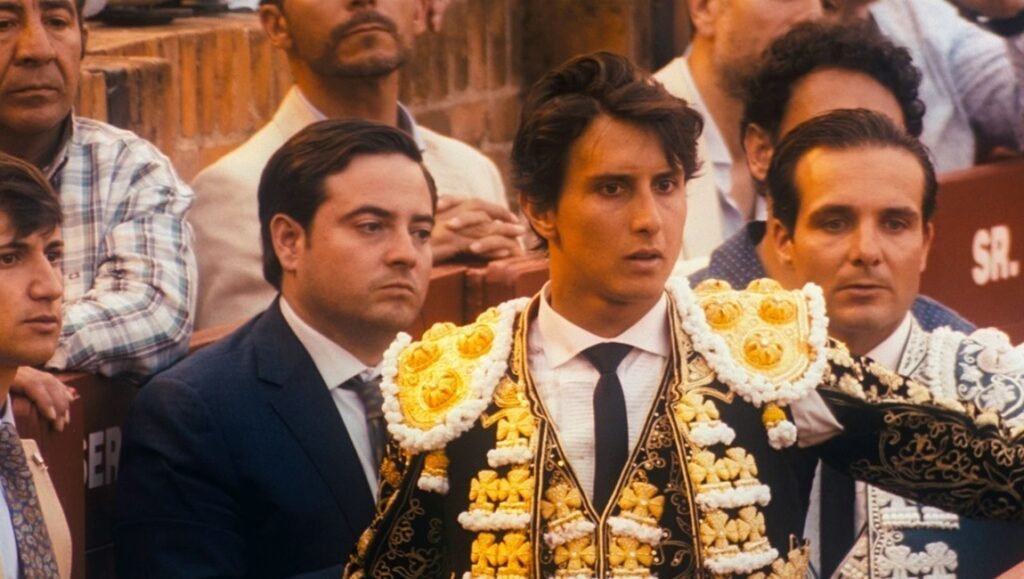

Following Pacifiction, his seventh and most technically elaborate narrative film, Albert Serra did something unexpected: he produced his first full-length documentary. Afternoons of Solitude is a clear-eyed but expressionistic examination of Spanish bullfighting, focused on top-rated matador Andrés Roca Rey. We observe the torero preparing and then executing four fights, one after the other. With unprecedented access, Serra displays the inner workings of the activity, with particular emphasis on the complex interactions between the matador and bull. Due to the nature of the subject, Afternoons is likely to divide audiences. While no one would mistake the film for a Frederick Wiseman documentary, Serra does adopt a neutral, objective cinematic stance toward this controversial practice. As is the case in his earlier films, Serra shuts out the larger world and asks his viewer to observe the small, private details that only the closest of attention can reveal.

Serra and I discussed the film in a brief conversation on June 27.

Michael Sicinski: What drew you to the subject of bullfighting? From the outside this appears to be a radical shift following Pacifiction, but maybe from your perspective it’s entirely logical.

Albert Serra: Bullfighting has always been very present in Spanish culture, of course. In the 19th century it inspired major artists like Goya and Lorca. But there is still a mystery to it. Why do people still do it? So, with modern film technology, I could look at it. I shoot a huge amount of images, and then try to solve the puzzle. I’m trying to extract the most fascinating, the most mysterious images from that footage.

So the methodology is similar to that of my feature films. In my feature films, the images are all very organic. A lot of wild, unpredictable elements, especially the performances. But at the same time, those images are very artificial. Sometimes it’s surreal. Like in Pacifiction, you never see a regular street with ordinary people. It’s almost a mental construction.

So I found that because bullfighting is already a ritual, it has that artificial element. So it could fit perfectly into my style. In bullfighting, there were connections to the things I respond to in cinema. Because it’s very violent. Because it’s very bloody. Because it’s unpredictable. Because it’s life-threatening. So there’s that wild, rough, organic aspect. Bulls are organic! But at the same time, it’s artificial. It’s a liturgy. Why do they do it? They repeat it, like any ritual. There is no goal. There is no ending. It’s just the repetition, starting again, starting again. It’s like some kind of spiritual activity.

Before I began shooting Pacifiction, the project was developing in parallel, and at first I saw it as a little bit of a side project. “Okay, let’s do a documentary, I’ve never done one.” (And there was no way to do it as a fiction film about bullfighting. It’s impossible.) I didn’t necessarily think it would be an important film in my corpus. But suddenly, it became obvious that it would be. The matador is so interesting, and the shooting allowed me to make the thing so intimate. Nobody has had this kind of access [to bullfighters] before. Nobody has been with the #1 matador during the biggest days of the season. No one has been allowed in the arena, or allowed to be in the room when they get dressed. Even their parents, the girlfriends or boyfriends, nobody gets in. Never! It’s regarded as a sacred place. Also, I got access to the team’s dialogue, when they are insulting the poor bull. “Son of a bitch,” they call him, or “criminal.”

MS: They treat the bull like he’s a bad sport, like he wasn’t playing his proper role.

AS: Yeah. So nobody has had access to all that. And it’s the highest level — the highest ranked matador on the biggest day of the year, the equivalent of Wimbledon for tennis. And I had access to these things that tend not to show. Because they have a very spiritual approach, and the fear is a very important element, so they don’t want people recording their conversations, or how they breathe, how they face down this fear. But I got it. I was very lucky.

MS: I’m not especially familiar with contemporary Spanish popular culture. And like you say, Andrés Roca Rey is at the apex of this sport. But in the film, bullfighting seems to be a decadent practice, something that is on the decline, or a sport that is out of step with contemporary reality. But I don’t know if that’s actually true, or whether bullfighting is resurging in popularity.

AS: Well, we’ve seen that different groups are promoting values that are not very modern, not going in the same direction that we see as the logical evolution of the world. Besides, we see that violence in the real world still exists, maybe even more in recent years. So it’s not that the violence is disappearing.

It’s true, it’s a little bit decadent, to perform this violence as a show. But at the same time, it’s… educational. There was an important Spanish writer who said, “of course it’s violent, of course there is some injustice to this practice, of course there’s a sadness to that. But for these reasons, it’s deeply educational.” It’s something that comes from a truly ritualistic place. It’s decadent, but… Spain is the country of irrationality. It’s the country of Franco and the Civil War. The country of some of the darkest conquest and colonialism. Part of our soul, the soul of human beings, if it still exists, is that you cannot be civilized so easily. It’s like the catharsis in Greek tragedy.

And besides, we tend not to have a problem when we see a ritual in the Third World. We say, “ah, this ritual is a symbol of purity.” But when we see it in Western society, we say “wow, this is not a symbol of purity. It’s a symbol of decadence.” We switch perspectives.

I don’t think it’s one thing or the other. The film tries to portray this in an artistic way, with all its complexity, going to the heart of it. I did not have any a priori about the corrida. If I want to use the camera and shoot a film, it’s because I don’t have any idea. And I want to see what the camera will reveal. I want to be surprised by the camera. I want to be surprised by the sounds. And I want to better understand and better appreciate what’s going on there. If I already had my own ideas [about it], I would write a book.

MS: One of the reasons why this film might be capturing viewers’ imaginations is that it reveals this specific kind of spectacle of masculinity, and masculinity seems to be a pressing problem around the world. There’s a surge in the aesthetics, of the sublimity, of masculine will. In the corrida, it’s overtly ritualized, whereas in other realms (such as politics) it’s even more dangerous when that aesthetic of machismo becomes ritualized.

AS: It’s not my fault! [laughs] I’m just portraying exactly what it is, what it’s made of. I concentrated on the torero in these more intimate moments, both by himself and in the intimate moments with the bull. I’m also trying to treat the bull with its own subjectivity. There is a kind of sadness; there are moments when he’s looking at the camera and he’s the only one who doesn’t know how it will all end. The others are conscious of how the ritual works. And of course it’s life-threatening. We see it in the film. The bull has his chances at the matador. A lot of the great toreros in history — some of them, a lot of them, have died in the arena. If you don’t die in that moment, it means you still have something to give. That you’re not done yet. In bullfighting, the greatest honor, somehow, irrationally, is to die in the arena. Because it means that you risked the maximum, and maybe you made a mistake, but you gave everything. You were committed and didn’t hold back.

But at the same time, the toreros are committed to artistic expression. They consider themselves artists, and this is the paradox of their masculinity, because there’s a lot of blood, and the show always ends with killing. But before that, everything involves this delicacy, these very small movements, these gestures of the body. They are meant to dominate the bull, but they do it with these very graceful, sensitive movements that are usually coded as feminine. And this connects with the costume, which is somewhat feminine. When you see them getting dressed backstage, there a strange ambiguity to that, even an eroticism. The torero and the assistants who dress him have a physical connection. There is something important there. So even though the ritual will end with the killing of the bull, there’s a delicate, spiritual force at work, alongside the brutality.

MS: Part of that is the camaraderie that we see. And something that seems to be at the heart of a lot of your films is the intimate relationship within a small coterie. Sometimes the audience is invited into that, and sometimes the audience is repelled.

AS: Yes. I think those moments are beautiful. The men make all these remarks about the bull, but when you look at their faces as they say these things, it’s almost Pasolinian. There is a kind of poetry [in their trash-talk], with sentences that are quite imaginative. “Life is worth nothing!” Aggression, yes, but always with some kind of delicacy, some kind of imagination. There is a fantastic popular poetry, something that fascinated a lot of artists, like Lorca, and maybe especially some of the homosexual poets. Because they were fascinated by this macho thing, but the delicacy that’s present there too. There is a beautiful shot near the end, when the torero goes out, and a member of his crew looks at him with a smile of admiration. And that’s one of the most humble things that can happen in life— when you recognize that somebody is superior to you. Remember, all the crew members and assistants, around 90% of them, are frustrated matadors. They couldn’t achieve Roca Rey’s status, or couldn’t accept the level of risk. So they remain as helpers. And they know how difficult it and the pressure you have to endure.

And I know how it affects the torero. I saw him on the day of the big fight, the night before and the next morning, and he was in a very bad humor. He wasn’t smiling, wasn’t making jokes. It’s like soldiers in a war. It’s not the time for jokes. It’s another state of mind. It’s both artificial and life-threatening. And so it’s strange.

MS: And the objectivity with which you show it allows the viewer to make his or her own decisions about the spectacle itself. I could imagine that a particular kind of macho, right-wing type of viewer would be cheering these guys on. This kind of pageantry of masculinity probably speaks to that kind of right-leaning attitude.

AS: Yes, of course, and this is a problem, because in the arenas most of the people watching this are right-wing. We don’t have to deny that. That’s the reality. But at the same time it’s a fact that, for example, at the beginning of the 20th century, those audiences were totally mixed [politically]. It was a very popular show. It was left-wing people, right-wing people. The ideological aspect of the violence to the animal, that’s very important to us. We’ve evolved. We don’t treat animals this way just for fun. But at the start of the 20th century, when there wasn’t this kind of thinking [about animals], it was a very popular thing, and it was linked with this popular poetry. People admired the toreros as heroes because they knew how to accept the risk and how to overcome that fear. It’s quite impressive.

And nowadays, even if you get close to the matador, his personality is a mystery. As you watch the film, you know the torero about as much at the end as the beginning. That reflects my experience. I followed him throughout the film, and by the end of making the film, I didn’t know him any better than I did at the beginning. I couldn’t really discover his reason for doing it. He’s already rich. He comes from a rich family. Why take this risk? It’s totally hermetic, what happens inside his mind. Maybe that mystery is part of the spiritual side of the sport, if there is one.

MS: I went back and watched your short film My Influences (2020). In that film you mentioned an interest in [French film critics] Michel Mourlet and Jacques Lorcelles — the so-called MacMahonists. They were interested in the overpowering sublimity, almost the violence, of the film image. While watching Afternoons of Solitude, it occurred to me that maybe you were tapping into that sublime violence, overpowering the spectator.

AS: Well, I’m sorry, I’m not a political man. I’m a filmmaker. This is a romantic thing, you know? To see the beauty in horror, it’s not me who invented that. It comes from Romanticism, or the catastrophes of nature that fascinate us. And death has fascinated all artists across history. It’s the darkest part of our soul, the irrational part of human beings that we also share with all of nature. It’s there, and you cannot cancel it, at least to judge from the real world. For me, that’s the value of the cathartic element of the Greek tragedy. We explore the dark parts of ourselves and we try to purify that through ritual. And it’s endless. We never achieve that goal.

MS: The film never makes an argument one way or another about bullfighting. While my own experience was one of being repelled, the act as shown eventually makes an argument for itself. It simply shows what is.

AS: Sure, and the torero, Andrés Roca Rey, was upset by the film. He hated it when he saw if for the first time. Because he said that it was too violent! He said I betrayed him, “I gave you all my generosity, all that access, something never before given to an artist, and you betrayed me.” There were big fights, and lawyers got involved, but then he calmed down, and now the film is successful. But he thought we were emphasizing the violence too much. But I didn’t think so. I thought it was at the right level. I mean, it’s part of bullfighting. What can I do? Maybe I was following the theory — I think it was in Cahiers de cinema — that all documentary must be a form of betrayal.

MS: It’s interesting he had that reaction, because it’s almost as if he was anticipating an anti-bullfighting film and so that’s what he saw, at least at first. But that’s not what Afternoons is.

AS: No, I couldn’t renounce the complexity of what I was seeing or what the camera captured. And part of the complexity is that it’s undeniably violent. Though it’s undeniably violent, to all the people who are watching the bullfight, it’s entertainment. So we have to accept that all of these people are accepting that violence. And I am getting very close to understanding why. The why is in the intimacy between the torero and the bull. Because it’s how we relate with our own animal condition, or how we relate with the world. It’s something that’s still there from the very beginning of humanity. All animals in nature kill other animals, and not just to eat them. There is violence in nature.

But I don’t know. I don’t have to defend [the toreros], because I don’t care. But I will defend what the images say, or what they show. I tried to calibrate all the elements captured in those images. That’s what the basis of film is, an anthropological document. But my main goal was always to make a personal film, an artistic film, and a film that stands alongside my previous fiction films. Beyond that? Bullfighting. Sure. Why not?

MS: And were you happy enough with how Afternoons turned out that you’d want to make other feature documentaries? Or was this a one-off?

AS: It depends on the subject. Like I said, this appealed to me because it contained those artificial and those organic elements that characterize my films.

Sure, I had a bit of knowledge about bullfighting, and appreciated the Baroque elements. But mostly I was innocent, and this allowed me to be honest. Because I didn’t give a shit about them. I’m not doing propaganda. That innocence is the most important element in all my films. How do we recapture that innocence, even with a topic that is so controversial? In Spain this is a constant battle. There are these ideological issues, right-wing sociological issues, folkloric elements. And I took all that out of the film. By eliminating the audience, I excluded the sociological as well as the folkloric. What’s left is something physical but also spiritual. The matador and the bull, inside the arena.

MS: What’s ultimately most impressive about the film is that, yes, it deals with the topic of bullfighting. Like you say, it’s a subject with a lot of sociological and political import. But like so many other things, people talk about it or talk around it, without really looking and investigating and understanding what it is. This film investigates and reveals what bullfighting is. So then we can have an intelligent discussion.

AS: Yes. You can still have your own opinion, but this will give you a vision that neither you nor anyone else has seen before. I think it’s worth those two hours. And of course I was fascinated. You know, at Lincoln Center I did a talk about Amos Vogel and Film as a Subversive Art. Amos Vogel has always influenced me. I won’t self-censor, in any case — not to please the torero, not to please those around him, or anybody else. So this kind of freedom was crucial. I wanted the film to have the dignity that, if Amos Vogel was alive, he’d maybe have a place for it in his book. To achieve that, you need extreme honesty.

Comments are closed.