Come a little closer and see — you need to inhale.

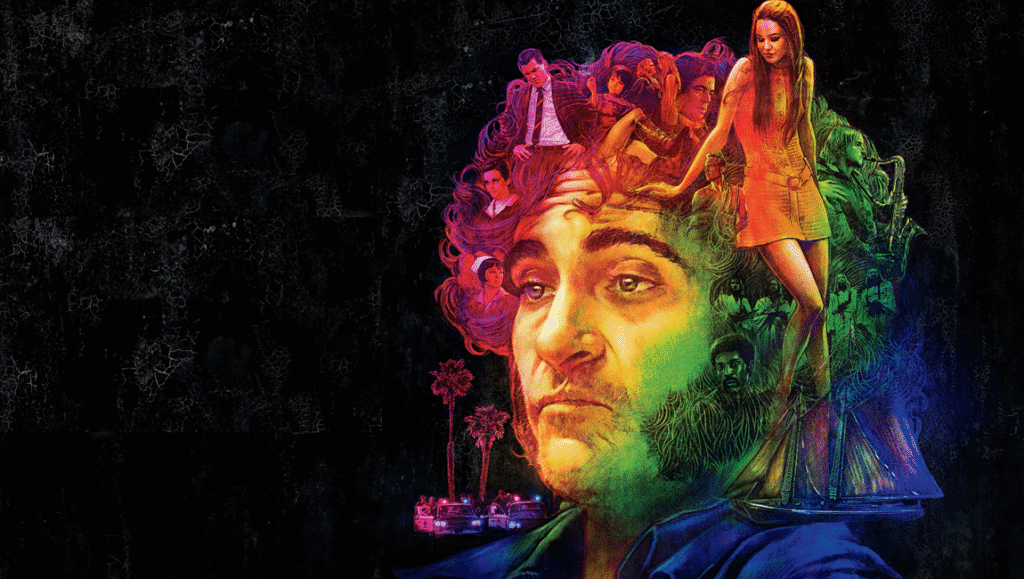

No contemporary filmmaker understands California quite like Paul Thomas Anderson, who throughout his rightfully vaunted career (save for, in this writer’s opinion, the wild misfire Licorice Pizza) has rendered it the perfect microcosm for all that is beautiful and ugly about America. Elsewhere, no writer from the back-half of the 20th century understands the rot infecting American systems like Thomas Pynchon, who in 2009 published a lighthearted novel about a hippie P.I. clawing his way through the thicket of an impenetrable conspiracy to find the woman who left him behind. At the intersection of these two artists, Anderson imbuing Pynchon’s farcical post-flower power Los Angeles with an astonishing nostalgic warmth, a vision of California was created that speaks to the contradiction at the core of American life: America is an inherently optimistic, youthful nation, but it is also a nation built on death, displacement, and the ruthless accumulation of capital. It might seem like nonsense until it suddenly reveals itself to you with perfect crystalline clarity in a whisper, a clarity that dissolves in a smoky haze as quickly as it came. Inherent Vice is that whisper: a hilarious, subversive, and melancholy elegy for the America we want, need, and can’t have. To understand anew the secrets the film reveals to us is what keeps bringing us back.

Or maybe it’s just how downright fun it is. Inherent Vice unfolds with such effortlessness that it feels almost improvisational. Faces superimpose over one another, shots melt into each other like half-remembered dreams, a cleverly placed line of dialogue pops us from one scene to the next. Take one look under the hood, however, and a meticulous craftsmanship shines. It’s astonishing just how in control Anderson is at the helm, particularly considering the freewheeling nature of the material. He rhymes his style with Pynchon’s, grabbing images from as high as the top of the Western canon to the bottom of the pop culture barrel: everything from Da Vinci’s The Last Supper to early-’70s primetime cop shows. He even does himself the favor of keeping huge swaths of Pynchon’s prose in voiceover, that, when delivered by Sortilège (Joanna Newsom) — the film’s narrator and conscience — is spun into sun-kissed gold.

But it’s not just Sortilège who gets to cavort in Pynchon’s wordplay: the entire ensemble works naturalistic wonders, cooling Pynchon’s pun-and-irony filled dialogue down to just the right temperature for the screen. So rare is the vast entertainment that is also finely in tune with its characters’ emotional lives, but here, Anderson and his actors — from top to bottom, and occasionally in only mere seconds of screen time — explore the interiority of these seemingly outlandish figures: a marine lawyer with a name resembling the first literary sidekick’s, a closeted cop obsessed with sucking on frozen bananas, a former heroin user with dentures the size of billboards. There’s such a rich plurality of voices in Inherent Vice, and not one of them feels false.

The story is shrewdly set during the twilight of the countercultural movement. Defiantly romantic, shoeless gumshoe Larry “Doc” Sportello (Joaquin Phoenix) is among of the last of a dying breed, and we see the collapse of the ’60s through his eyes. Not long into the movie, we join Doc for a smoke session in honor of the ex-old lady he’s looking for, Shasta Fay Hepworth (Katherine Waterston). In extreme close-up, we see Doc write a dedication to her on his rolling paper as Sortilège — or he, or maybe it’s both — ruminates on what ended the relationship. “Does it ever end?” Sortilège asks, Doc blowing smoke into his ceiling as if in offering. “Of course it does. It did.” Shasta becomes something of a beacon for Doc, someone representative of the hippie lifestyle and its degeneration as he stumbles around a Los Angeles buckling under the weight of privatization.

In one of the film’s most poignant scenes, Doc recalls running barefoot in the rain with Shasta. The sky is both cloudy and not, and the sunset pokes through in a sliver of pink on the horizon. They dash by an empty lot looking to score some dope, Anderson’s camera tracking back and forth with them in childlike bliss. They find none, but end up having the time of their lives in each other’s arms under the façade of a closed laundromat to shelter from the storm. In the next scene, Doc walks by that same lot in the harsh midday sun. A gigantic office building in the shape of a golden fang — the name of the cabal Doc has been brushing up against which may have something to do Shasta’s disappearance — sprang up and replaced the lot. The hard juxtaposition of two iterations of the same location, shot under Neil Young’s “Journey to the Past,” is a crushing reminder of days come and gone. Places change, and not always for the better, but memories remain.

Dashing in and out of the frame here — sometimes literally — is a very earnest consideration of gentrification, race, and economic disparity. In an early consultation, Doc meets Tariq Khalil (Michael Kenneth Williams) of the Black Guerilla Family at his office. Tariq describes that when he got out of prison and returned home, his gang wasn’t just gone — his entire neighborhood disappeared. Real estate magnate Mickey Wolfmann (Eric Roberts), who Shasta’s been cozying up to as of late and also may have something to do with her disappearance, tore it down to make room for a new housing complex. Naturally, Doc drives there to snoop around. As he does, who runs beside his car just out of focus but two wandering Black boys? And in case it wasn’t clear enough, Sortilège joins Doc for the ride to bemoan the “long, sad history of L.A. land use.”

Anderson peppers wry digs at American institutions throughout the film. Members of the LAPD yuk it up at a pool party, the camera panning across the goofy tableau from behind window blinds. Doc makes a clandestine tradeoff with an antagonistic mother-and-daughter duo, Sam Cooke’s “(What a) Wonderful World” sarcastically lilting from the radio as two cars sit in an empty parking lot, probably for a mall — a brutalist building of the banal sort we saw proliferate in the ’70s and ’80s, which reached their apex in the ’90s and now sit dead across the nation. Doc also finds his way to Chryskylodon, a private mental institution run by rabid anti-communists. One of the film’s funniest cutaways features a certain Dr. Threeply (Jefferson Mays) — eyes wide, face ruddy with jingoistic enthusiasm — mouthing along to the old American propaganda picture playing for his patients.

Doc eventually shakes the doctors giving him a tour at Chryskylodon and tiptoes his way around the campus. He finds Mickey Wolfmann resting under the custody — or guidance — of the FBI. Anderson switches to handheld briefly, following behind Doc. Doc’s confrontation is then shot with an Ozu-esque precision, Doc framed perfectly by stucco and tile. Mickey reclines in a huge leather chair, shot from below. “What are you doing here?” Doc asks, bemused. “They’re helping me wake up from my bad hippie dream,” Mickey responds. Eric Roberts plays Mickey with glass-eyed vacuity. “I dreamed I gave away all my money… I spent my whole life making people pay for shelter, and all along I didn’t realize it was supposed to be for free.” It’s the final salvo for the spirit of collectivism the late ’60s embodied. Mickey wakes up. “Go away little hippie,” he waves, glass eyes sharpening to steel.

There’s a narrative decompression after Doc bumps into Mickey Wolfmann at Chryskylodon, as if in some sense the story has ended. Doc didn’t find who he was looking for, but everything seems to return to normal — or something resembling normalcy. Yet there are still 50 minutes of movie left. Where’s Shasta? Doc does indeed find her. Really, she finds him. Shasta reemerges at Doc’s apartment and almost immediately undresses. For all the sexual tension in the movie, and all the playful references to it, the sex they then have is decidedly unsexy. Shasta talks about being submissive and invisible. “Not what you’d call a considerate lover,” she calls Mickey. “But we adored it about him.” Her foot makes its way up Doc’s thigh toward his crotch — the effect is almost scary. The sex is short and angry; Doc does a bad impression of what he assumes Mickey would do, trying to be the man he knows he isn’t. A single tear trickles down Shasta’s face. “This doesn’t mean we’re back together,” she concludes. Free love is well and truly dead.

But there’s one loose end still giving Doc consternation. His whole journey has been punctuated by run-ins with Coy Harlingen, an Owen Wilson removed from Bottle Rocket’s Dignan only in the sense that his hair is longer. He’s guileless, frank, and more than a little corny. Coy fell in with the wrong crowd, and through a series of loosely connected pinball bumps, Doc gets put in the position to help Coy out and deliver him back to his family.

Often in Inherent Vice, Anderson’s camera will lean in as if listening with intent, trying to pick up a hidden meaning. That changes when Doc picks Coy up from a cult in Topanga Canyon, setting him free: the setting sun bursts directly into the lens, and Jonny Greenwood’s score — heretofore ominous and tense — settles down with harmonium and muted horn. In front of the Harlingen home, the camera pulls back to grant Coy the privacy he hasn’t had in a long time, revealing the warm orange glow emanating from his house. We push back into Doc’s car; he looks down. Coy’s wife, Hope, laughs offscreen. California is kooky and depraved and malicious and gorgeous and sensuous and wicked, but for many it doesn’t stand for anything at all. It’s a place for belonging, community, and family. It’s home. Inherent Vice falls apart without this subplot — for all the kicking Doc does against these systems of oppression, devoting energy to reuniting a small family is the beating heart of the movie. Without it, there would be no Hope.

Inherent Vice opens in the ethereal light only a California dusk can offer; it ends in the dead of night. Doc drives down a road with Shasta on his shoulder. An alarming square of light burns into his right eye, then darts away. He looks through the windshield — up and around. “This don’t mean we’re back together,” he says, echoing Shasta’s earlier sentiment. “Of course not,” she whispers. The light returns, puncturing their shared sense of complacency. Doc looks once more at the rearview mirror, then looks ahead. He gives an ambivalent exhale. Cut to black, and then the title appears. It’s two seconds, but it’s enough to tell us what Doc sees: total darkness.

A lot of directors like to pull this magic trick wherein they end their movies with a pop song that perfectly encapsulates the timbre of the preceding couple hours and change. It’s a fairly common sleight of hand — irresistible, in its way. The Holdovers and The Irishman do it well, to name a couple recent examples, but Inherent Vice’s might be the best of them all. The haunted strings of Greenwood’s score crescendo, and the hard thumps of Chuck Jackson’s “Any Day Now” begin. The song is eight months pregnant with portent. “Oh, my wild, beautiful bird, you will have flown,” Jackson cries. The future perfect tense is, at best, naïve. In reality, it’s closer to desperate. “Until you’ve gone forever, I’ll be holding on for dear life. Holding you this way, begging you to stay.” Jackson screams to have his voice heard by this disappearing love, stretching the vowels to steal a few more moments with his beloved. The song ends with a slow fade, Jackson’s plea tripping into oblivion.

In having Doc fight for a single act of kindness against the brick wall of bureaucracy and capitalism, Anderson makes it clear: the spirit of the ’60s is gone, this bird has flown. Question is, where is the bird flying to? Late in the film, Sortilège gives us a clue, or at least a possible destination: “May we trust this blessed ship is bound for some better shore, risen and redeemed. Where the American fate mercifully failed to transpire.”

Now look the other way — exhale.

Comments are closed.