Lilim

An overwhelming sense of familiarity clings to Mikhail Red’s Lilim, which liberally deploys Gothic and folk horror tropes without grasping their inherent power. The film begins jarringly, with a scream: Issa (Heaven Peralejo) has murdered her abusive father in self-defense, and she quickly flees the scene with her young brother, Tomas (Skywalker David). The siblings soon take refuge in the remote Helping Hands Orphanage, populated by adult nuns and orphaned boys.

Lilim suggests intriguing allegiances to fairytale logic. From the outset, it emphasizes the menace of its central orphanage, which is nestled in the forest and decorated with paintings that invoke the darkest visions of Goya and Caravaggio. Shortly after the siblings arrive, the Helping Hands nuns conspicuously dismiss a weeping man who bolts down the hall. A demonic face appears in the ceiling of the boys’ sleeping chamber, visible to the audience but unseen by the players onscreen. Issa and Tomas learn of Mother Mirasol, the orphanage’s oldest member, now confined to a locked room. The boys refer to Mirasol as a beast who roams the site looking for children to eat, and the nuns treat her like a deity; a nun who accidentally breaks a Mirasol statue is forced to walk barefoot across the shards while reciting reverent phrases.

As the orphanage’s inner dramas unfold, Lilim neglects to seriously address the murder that instigated the siblings’ arrival. The film also loses its focus on the ensuing police investigation, which is hastily reintroduced as a plot contrivance in the final act. Although the narrative maintains a constant threat of danger, and frequently teases the emergence of the monstrous Mirabol, it is otherwise peculiarly devoid of tension and momentum. Lilim builds itself on one of horror’s age-old tropes — the interplay between the sacred and the profane — a theme perennially ripe with visual and metaphoric potential. Unfortunately, however, Lilim is too timid and routine in its depictions of the profane, and it seems entirely uninterested in the metaphysical heft of the sacred.

Red’s film is sturdily made in technical terms, but it ultimately doesn’t rise much above a mechanical exercise. It’s so generically lockstep that its characters become abstractions, even despite Peralejo’s best efforts (she is an innately impressive screen presence). The forceful music cues, meanwhile, function in sum to emphasize the lack of imagistic impact rather than contribute much to compensate for it, and a series of theme-telegraphing monologues drift in and out of scenes without lasting effect. One of the nuns tells Issa that absurdity is part of faith, and one can’t help wishing that this film indulged in a little bit more of both. — MIKE THORN

Bel Ami

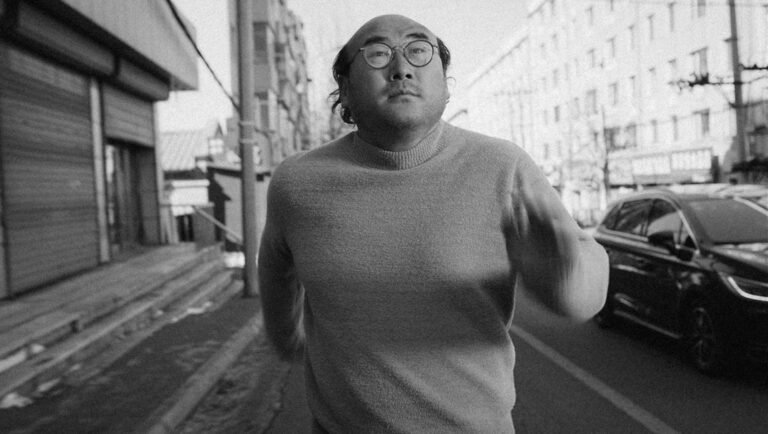

Bel Ami is a curious and often compelling entry in the canon of queer Chinese cinema — one that blends stylized melancholy with pointed political subtext. Filmmaker Geng Jun’s most sophisticated critique emerges not through overt polemic, but through a clever parallel between queer dynamics of dominance and submission and the repressive structures of state power. In one standout scene, a male character sings the communist anthem “The Internationale,” invoking both the revolutionary spirit and the double meaning of tongzhi (comrade/queer), while subtly rebuffing the authority of a queer woman who attempts to curtail his agency. In another moment, two women engage in a kungfu-esque pantomime — an absurd yet moving gesture of resistance and solidarity, casting their queerness as part of an imagined jiang hu, a mythic underworld where alternate forms of connection and belonging flourish amid societal constraint.

Unlike Geng’s previous work, which often traps its characters in noir-inflected spirals of bad luck and worse decisions, Bel Ami yearns for something more emotionally direct — an earnestness that sometimes feels at odds, and in nonproductive ways, with its own airless aesthetic design. The film’s black-and-white cinematography, almost incessant Gallic score, and even its French-language title all betray its seeming ambition to convey the painful, raw realities of queer life in today’s China. At its best, the film offers glimpses of that aching clarity — of queer desire as both a tender impulse and a political act — but its self-conscious stylization too often curdles into pandering arthouse-isms.

Shot seemingly under the radar of censors in remote Heilongjiang province and produced by the Paris-based Blackfin Production, Bel Ami follows the now-familiar path of recent queer Chinese films that navigate censorship by relying on international funding. There’s nothing inherently wrong with that approach — but paired with the film’s conspicuously Westernized stylistic gestures, Geng’s vision loses some of the specificity and urgency found in the best of China’s queer underground cinema, by directors like Cui Zi’en, Ying Weiwei, and Jiang Zhi.

Ultimately, Bel Ami stands as a telling case study in the gentrification of Chinese arthouse cinema, a trend that increasingly resembles the dynamics of the “world music” market from two or so decades ago. With little domestic infrastructure to support truly subversive or innovative filmmaking, many Chinese directors turn to international support, but their interlocutors often remain more focused on satisfying the demands of global festival audiences, and the slates they curate tend to be populated by films that feel like vaguely Sinicized versions of familiar European arthouse tropes. Geng is clearly more talented than most working within this export-oriented model, but he still falls into many of the same traps with Bel Ami. — SAM C. MAC

A Girl with Closed Eyes

Director Sun-young Chun’s feature debut, A Girl with Closed Eyes, begins with a deceptively simple setup: a woman named In-seon (Minha Kim) shoots and kills a famous writer, Jeong Sang-woo (Lee Ki-woo), in his remote home. Police arrive at the scene and find her still holding the murder weapon. She freely confesses to the crime, and the cops write it off as “a Misery scenario,” labeling In-Seon a deranged stalker who murdered the object of her literary obsession. In-Seon alleges that Jeong Sang-Woo based his bestselling novel, A Girl with Closed Eyes, on her own childhood kidnapping and abuse. Initially, police dismiss her claim. As the investigation moves ahead, In-seon refuses to cooperate with anyone but Detective Min-ju (Moon Choi), a lone woman in an overwhelmingly male police force, with whom In-seon allegedly shares a complicated past. The case soon reveals itself to be much less simple than initial appearances suggest, involving a range of shadowy suspects and untold histories.

A Girl with Closed Eyes serves as an exercise in content-through-form: it’s an excessively twist-filled narrative about the complexity of narratives. It’s filled with written and oral accounts — police interviews, text messages, novels, legal contracts, and YouTuber theories; a vortex of opaque intentions, hidden identities, stories-within-stories, conflicting testimonies, and clashing cultural and individual perspectives. A phrase is inscribed into the handle of the gun that took Jeong’s life — the truth will set you free — signaling the film’s primary moral focus. The question of fiction versus reality hovers over everything. Girl’s mazelike plot concludes with unmistakable condemnations of victim-blaming, misogyny, and abuses of power both individual and systemic. Mysteries cloud the question of who fired the gun, but there’s no mistaking its symbolic targets.

A Girl with Closed Eyes ultimately falters in narrative terms, but it’s not without merits. Director Chun Sun-young demonstrates an aptitude for staging, especially during sequences set at Jeong’s modernist home — expansive frames capture the space’s steely elegance, concrete walls surrounding floor-to-ceiling window views of a snowy landscape. Early interrogation scenes between Min-ju and In-Seon crackle with spoken and unspoken drama, and Moon Choi is a strong lead, deftly managing her character’s evolution from staid resolve to emotional revelation. The film also maintains tension through much of its dialogue-heavy proceedings. But The Girl with Closed Eyes eventually loses momentum by the end of its second act, and at 106 minutes it feels dauntingly overlong. By the time the third act arrives and cedes ineffectively to overwrought melodrama and tidy resolution, viewers are left to contend with the lingering impression that Sun-young’s film has somewhat undersold the impact of its weighty themes. — MIKE THORN

As far as titles go, few films are as aptly and succinctly summed up by their own as Transcending Dimensions. The latest project from Toshiaki Toyoda (Blue Spring, 9 Souls), the film is a psychedelic and cosmic odyssey that expands from this mortal coil to the ends of the known universe, exploring the limits of mankind and the potential greatness that can be attained. Packaged into a dense 90 minutes, Transcending Dimensions regularly flirts with incoherence, but often in thrilling ways, with Toyoda delivering an entertaining narrative loaded with psychic-powered confrontations, hallucinogenic visuals, and the eternal enigma of a magic conch shell.

Transcending Dimensions’ central plot concerns the disappearance of Rosuke (Yôsuke Kubozuka), a monk who was seeking to transcend his own being prior to going missing. Tasked with finding the monastic man and eliminating everyone responsible for his disappearance is Shinno (Ryuhei Matsuda), a hitman hired by Rosuke’s sister, Nonoka (Haruka Imou). Shinno infiltrates the inner circle of Master Hanzo (Chihara Junia), a cruel sorcerer who runs a cult and takes sadistic pleasure in maiming his followers. Preaching a lifestyle devoted to asceticism, Hanzo relies on his telekinetic powers to bend others to his will, capable of exorcising maladies and swaying the meek into severing off their own fingers to act as vessels into the great unknown. As it turns out, Hanzo also happens to be funding the very research facility that is holding Rosuke captive, where the monk’s mind is integral to unlocking the secrets of the universe (along with some assistance from artificial intelligence, natch). Meanwhile, Rosuke is venturing out on his own interstellar journey, exploring a spaceship seemingly millions of miles away from earth, where the rooms and hallways boast vivid kaleidoscopic designs and the lone inhabitant is another fellow monk. Through this quest, Rosuke appears to be unlocking some abilities of his own, as all characters hurtle toward a violent climax destined to spill blood. Also in the mix is the aforementioned magic conch shell that summons the monk and apparently eliminates the desire for all earthly pleasures when used — again, natch.

Transcending Dimensions opens with a piece of bravura filmmaking, kicking off with an understated but staggering shot of Rosuke’s reflection in a body of water as the camera tilts up to meet the man mid-meditation. These stunning formal traits welcomingly linger throughout the feature, as Toyoda’s camera appears not to be bound to any plane of existence, swirling and weaving in and out of prolonged sequences of behavior and discovery. Sonically, the film also impresses, employing terrific synth and jazz scoring that lends Transcending Dimensions a thrilling propulsiveness. These qualities coalesce into a show-stopping excursion into outer space, guided by the jamming soundtrack of “Inner Babylon” by Sons Of Kemet. It’s a total knockout sequence, and for fans of the beloved late title card drop, this is your Christmas morning.

But while the film’s continuous formal astonishment leaves any complaints against its style or technical chops feeling like bad-faith judgments, Transcending Dimensions does leave a little to be desired narratively speaking, hinting at an eventual Akira-esque showdown that sadly never comes to fruition, even going so far as to tease with a shocking visual of a man’s brain being summarily ripped out of his skull. In fact, for a film that occasionally engages in some fun telekinetic duels, Toyoda ultimately and surprisingly holds back on anything resembling an exciting showdown, opting for a more pensive exit. Still, Transcending Dimensions is consistently twisty and perplexing, and it typically lands with the right flavor of puzzlement, offering an undeniably good time audiences willing to submit to the mystery and particular flavor of indecipherability. Oh, and did I mention that there’s a magic conch shell. — JAKE TROPILA

Comments are closed.