Abortion Party

Aside from the infamous “Barry Lyndon x ‘a lot’ by 21 Savage” edit that has been circulating on X since last year, the TikTok video titled “My Weekend as a 28-year-old in Chicago“ has become the most beloved non-cinematic audiovisual creation among our very niche (!) online film community, of which I’m also a not-so-proud member. Conceived by comedian Judd Crud, the video parodies lifestyle content in which an increasing number of TikTok and Instagram users depict their daily routines — filled with motivational and seemingly meaningful activities — carefully crafted to sustain the illusion of personally and socially fulfilled lives. Whether it concerns these idealized routines or their exaggerated, cynical parodies, chronically online audiences love well-narrated “personal lores.” And whether we like it or not, their signature style — fast-paced, bloated with information and trivialities, digressive narration usually delivered in voiceover — seems to be sneaking into cinematic language; ergo, this extremely long and tangential introduction to Julia Mellen’s FIDMarseille–selected short Abortion Party.

With visuals created using the 3D design software SketchUp — which she had already been using in her previous work — it’s obviously not her DIY-style, minimalist geometric animations that led me to make this connection, but rather the way they contrast with her patchy and expansive ramblings, punctuated by a hyperbolic use of Internet slang and a considerable number of “anyway”s and “whatever”s. Mellen frames her film as an application video for a program at an institute, in which she recounts how she got pregnant at the age of 20 and decided to throw an abortion party. As she sits in front of her camera, introducing her Polish boyfriend Stefan, yapping about how one of her weirdo neighbors showed his own porn video during the party, casually info-dropping names of guests, friends, and neighbors, her rectangular image moves haphazardly within the frame — awakening, in my mind, a fond visual memory of the Windows XP logo drifting across my PC screen in pause mode. Conversely, her floating figure also echoes the “overlay effect” that content creators usually employ and which, through layering, virtually transforms the background image to an analytical or critical space — that is, as much as they can be on social media. Highly contemporary in its parlance, yet nostalgia-driven in its simple formal components, Abortion Party is indeed a peculiar object.

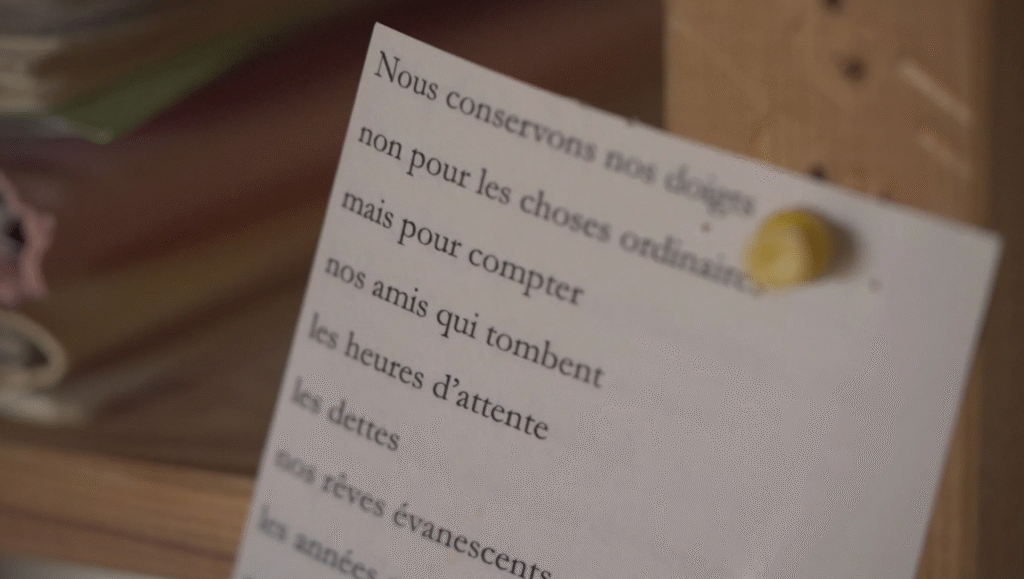

Mellen underlines — not without a dab of humor — how “topical” the concept of abortion is these days, and alludes to social and political transformations through the gentrification of Chicago’s Pilsen district, where she used to live. Yet the mise en scène, and the way it connects to her style of narration through pacing and movement, consistently overshadows the film’s discursive weight — something further emphasized by the distance and playfulness with which Mellen approaches her own past. In real life, SketchUp might be used for 3D modeling by architects, but down here in Mellen’s memory lane, cylindrical and cuboid bodies, cyan eyes, and magenta lips embody what remains after the passage of time. At the same time, these spaces are populated with contrastingly vivid and distinct imagery — such as Chicago’s sightseeing highlight, the “Obama Kissing Rock,” or Yung Lean posters decorating the room — depicted not through graphics but via photo inserts. As for textual elements, they often remain unrecognizable for a while — until the virtual camera’s movement shifts the angle within the frame, transforming nondescript three-dimensional prisms into meaningful language units.

In the interview she gave to FID ahead of the festival, Mellen mentions her aversion to “artspeak,” while also acknowledging its necessity in certain cases. It’s unclear whether she would deem this text necessary artspeak — but it’s hard to stop a film lover from being fascinated by the superposed yellow and white circular shapes created with digital graphics that represent vomit on the kitchen floor. If artspeak it is, it’s topical too, and to paraphrase Mellen, “y’all love that!”

Some of You Fucked Eva

The central question regarding contemporary experimental found footage practices is whether it is the artist’s vision and decisions that bring forth the evocative power of the images — or whether their very presence, through the mere act of appropriation, is potent enough to mask creative laziness. Yet being lazy, letting the images speak for themselves — couldn’t that, in itself, be an artistic decision, or at least an intention? To whom, then, do we truly owe the merit? To the past?

In times when works are motivated less by scarcity than by abundance and accessibility, an increasing number of films on the festival circuit seem to take the aural force of secondhand images for granted — and their growing presence alarmingly, to be leading to a homogenization of how such images are perceived. Not to underestimate the precarity in which these films are made and circulated, but medium specificity is nonetheless threatened by the conceptual flatness and hollowness of the regurgitated prefixes they claim to make use of.

Lilith Grasmug’s short Some of You Fucked Eva, selected for FIDMarseille’s Flash Competition, is, in this respect, a relevant case in point, as her film engages with the representation of American youth — arguably one of the most stereotyped sociocultural phenomena, that feeds its own stereotypification through repeated reproduction in mainstream audiovisual media. Grasmug’s film features anonymous videos gleaned from the Internet, which depict the mundanities and typical figures of American high school life — cheer squads, sports teams, yearbook portraits, prom dates, and petty gossip. Reprocessed with zoom and slow motion, these visual relics of the late ’90s and early aughts are framed through a voiceover narration by high schoolers Jonathan, Melany and Ruth, who recount an incident of “collective hysteria.” The incident in question concerns a group of cheerleaders who simultaneously experience seizures and faint in the school cafeteria. Their shared experience epitomizes — albeit without subtlety — how the myths and rituals of American society deprive young women of individuality and force their minds and bodies into predetermined categories.

Grasmug’s montage imagines their story through the lens of codified behaviors, gestures, and settings, all condensed within the recycled footage. Yet from all the faces that pass across the frame, not a single impression remains — it’s as if they’ve been molded into an indistinguishable visual mass. Even the titular Eva, introduced as the first to faint and granted a more personal and detailed account than “the other girls,” is bereft of singularity. A conscious, criticism-driven artistic decision it may be, Some of You Fucked Eva nevertheless seems to rely on this approach to further obscure its own codified style and character within the context of found footage practice — ultimately leaving an impression that is just as unremarkable and generic.

Control Anatomy

One of the most devastating consequences of the Israeli war machine and its systematic aggression against the Palestinian people is the hyper-mediatization of their suffering — even when the intent is to show solidarity or denounce Israel’s crimes — which ends up generating a normalized, perpetual, and atemporal state of genocide. There are no extreme limits left for representation. The more violence is shown, the more it becomes normal and bearable. The Israeli army killing civilians, starving them to death — how long has it been since these inhuman crimes became ordinary realities, ones we distance ourselves from through images? If images themselves are complicit in amnesia and indifference, then why make more?

Palestinian artist and filmmaker Mahmoud Alhaj’s film-essay Control Anatomy seems to be informed by this very question as well. Closely connected to Alhaj’s broader artistic practice, the film seeks to unearth both the temporal layers and spatial configurations of Israeli control and surveillance mechanisms over the years on the Gaza Strip. Beginning in the late 1980s, Alhaj delineates three modes of control — or rather, “generations,” to use his own term — each implemented through and dependent on the military technologies of their time. Accompanied by a first-person voiceover narration, Control Anatomy features a varied range of still and moving images, including Alhaj’s own artworks. What Alhaj describes as the first generation corresponds to a time when military rule in the refugee camps carried a social and interpersonal dimension. The images he reappropriates in this segment reflect the angle and level from which power was exerted. Humans — their bodies, faces, emotions — remain visible, and it is almost impossible not to be lured by a sense of nostalgia for the past. The second generation coincides with the beginning of the Second Intifada, its modus operandi defined by soldiers’ rifles aimed at civilians within shooting distance, while the third generation is marked by drones that dominate the Gazan airspace, maintaining a continuous and dehumanized form of control.

Although Alhaj’s film predominantly uses and engages with operational images — which constitute the foundation of the current ultimate stage of violence and mass destruction deployed by the Israeli military — it does not go so far as to fetishize them through abstraction, as many experimental or essayistic works tend to do. Control Anatomy argues that, even more insidious than the occupation itself, Palestinian lands have become systematized war laboratories and testing grounds for the Israeli army to optimize and perfect its technologies of destruction. Even the deaths themselves are fed as data to the war machine — which is personified through the mythological figure of the gryphon. How the gryphon should be imagined (or seen) appears to be intentionally left ambiguous. It is a curious — and pessimistic — proposition to liken the entire military force and its systems to this creature, since Alhaj’s metaphor goes beyond merely naming it: it finds in the gryphon’s grotesque characteristics an image of Israel’s inconceivable yet ever-growing destructive force. In Alhaj’s work, reframing and recontextualizing the present through another temporality echoes a narrative strategy which can also found in the sci-fi-inspired films of Larissa Sansour and Søren Lind. At a moment when all eyes are (or at least should be) on Palestine, filtering the gaze through myths, dystopias, and imaginary figures might seem destabilizing. But when the eye begins to see nothing by dint of looking too much, the time comes to recalibrate the focus — even at the risk of losing one’s footing.

Atelier Rolle, un voyage

If you go to Google Maps and type “Rue des Petites-Buttes 2, 1180 Rolle, Suisse,” the search results will bring you to “Maison de Jean-Luc Godard,” registered as a cultural monument, virtually accessible thanks to some distorted Street View shots — and even rated five stars. Jean-Luc Godard had actually been living in this modest house in Rolle for a long time already, but in his later years, he was known to have chosen a more isolated lifestyle, reserved for a trusted few. Over the last decade, his residence might have first come to widespread public attention when he famously didn’t answer the door to Agnès Varda and JR in Visages Villages (2017) — culminating the film in absentia in an emotional ending. But it is another final scene, also involving the same house, this time in Scénarios, that leaves one of the most poignant and long-lasting impressions centered on Godard to date.

With flowers left at its doorstep and “I <3 JLG”s scrawled on its windows after his death, some (overly) sentimental cinephiles may be tempted to treat the house as a place of worship, but for his close collaborators Fabrice Aragno and Jean-Paul Battaggia, it is presented as what it had always been: a workshop. In their joint project Atelier Rolle, un voyage, which premiered at FIDMarseille in June and focuses on Godard’s studio in Rolle, the Battaggia-Aragno duo adds a new piece to their ongoing series of creative propositions, rooted in and expanding upon Godard’s work.

Watching someone move up a staircase in the very first shot of the film, the viewer is initially tempted to liken the experience to a virtual tour, as one might take in a museum. But once the camera turns left and enters the room, a purple Dyson catches the eye — then a messy wooden table, four chairs, one with a tailored coat draped over it. The entire setting, laden with a vivid and immediate sense of intimacy, collides with the solemnity of the context. Throughout the rest of the film, we are invited to wander through the odd corners of Godard’s house, to observe (and admire!) the shelves laden with books, DVDs, and videocassettes, and ultimately to reconnect with the familiar relics from his life and his cinema. Since the film is shot in extreme close-ups, the visual proximity to the artifacts is countered: first by the inevitable blur at the edges of the frame, and second, by the movement inherent to the cinematic apparatus, which constantly impedes the viewer from getting a full grasp of what is visible.

Following a similar aural approach, the film appropriates sound excerpts from Godard’s work — predominantly from Éloge de l’amour and Notre musique, two films that also played a central role in Battaggia and Aragno’s earlier in situ creations, particularly Éloge de l’image, presented at La Ménagerie de Verre in Paris in autumn 2022. While different in form and spatial approach, Atelier Rolle can nevertheless be seen as an extension of their motivation to offer the audience the possibility of creating alternative itineraries, associations, and meanings within Godard’s images and words — of reflecting on different ways to set them in motion, so to speak. Moreover, Atelier Rolle doesn’t attempt to emulate the artificial coziness of Fondazione Prada’s Le Studio d’Orphée — a work that also explores the spatial configurations of the artist’s studio. Unlike its avatar, furnished within the rigid and static white cube, the studio—once transposed into the image — retains the freedom to be evasive, ambiguous, and at times invisible. While the gallery space imposes stricter “house rules” on its guests, the cinematic apparatus always appears to be more flexible — and today more than ever — allowing viewers to be both intrusive and disruptive. In this regard, as contradictory as it may sound, Atelier Rolle would ultimately also appeal to those who pause each frame, rewind, and replay to catch every single book, cassette, postcard, or cigar Jean-Luc Godard once owned — to detect which quote comes from which film — those inclined to turn films into treasure hunts; those who believe that the deeper they go into a frame, the more meaning and knowledge they’ll uncover; and those who know they won’t, but still can’t help trying.

Comments are closed.