The confluence of factors that led to the production of Targets encapsulate the idiosyncratic period in film history it was born into: in 1968, when the film was released, the institutions of studio-era Hollywood were crumbling, though vestiges of cinema’s past still held on; in their shadow, the inspiration and chaos of New Hollywood emerged in fits and starts. Roger Corman, the prolific producer of low-budget exploitation films aimed at young audiences, had assigned the auteurist critic and aspiring filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich a film to direct in 1967, after his successful stint as a second-unit director and uncredited script doctor of the Corman-produced biker flick The Wild Angels. Corman allowed Bogdanovich free rein in terms of content, but within an odd set of parameters that were characteristic of the budget-minded producer. Corman had discovered that Boris Karloff, the iconic star of ‘30s and ‘40s Universal monster movies that he had cast in several recent horror films, owed him two days of work. Bogdanovich would direct Karloff for two days, and he would also be required to repurpose 20 minutes of an earlier Corman film featuring Karloff, The Terror, within the new film to justify crediting Karloff as the star.

On paper, this is an impossible job, particularly because Bogdanovich and his then-wife, production designer, and all-around creative collaborator Polly Platt both deemed The Terror to be an unsalvageable movie. Yet Bogdanovich — with the help of director Samuel Fuller, who provided an uncredited screenplay revision — cannily used the restrictions placed on him to his advantage, and did so successfully enough that Karloff, who was in poor health, volunteered to work extra days with no additional pay. Bogdanovich crafted a dual narrative in which Karloff would play Byron Orlok, an aging horror star closely modeled on Karloff himself, who decides to retire after watching the dreary final cut of The Terror. Simultaneously, an unassuming young Vietnam War veteran and firearm enthusiast makes the inexplicable decision to embark on a shooting spree — which culminates at a drive-in screening of The Terror where Orlok is making his final promotional appearance. Bobby, the mass shooter played by Tim O’Kelly, was inspired by Charles Whitman, a Vietnam veteran who had shot dozens of people from atop a tower on the campus of the University of Texas at Austin in 1966.

In Targets, Orlok complains to the young director Sammy Michaels (played charmingly by Bogdanovich himself), who tries to convince him to take a part in a new screenplay he’s written, that he has become obsolete. While his career was built on scaring audiences, the fear of real-world violence has overtaken the fear of fictional creatures lurking within Gothic castles, and Orlok moans that audiences have designated his films as “camp! High camp!” Orlok’s commentary, of course, is metatextual: the dual narratives of the faded horror icon coming to grips with his legacy and the chillingly blank mass shooter plotting and executing his murder spree stages this conflict on a literal cinematic level, and Bogdanovich wrestles as much with the reflexive dismissal of the past as he does with the banal, purposeless violence occurring in the present.

Reviews of Targets upon its release, and more recent reappraisals, have focused primarily on Bogdanovich’s unflinching treatment of a mass shooting. Critics and audiences were indeed primed to view the film as an explicit critique of gun violence, because a condition for the film’s distribution by Paramount — following the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy — was that it include a note at the beginning that makes an explicit call for gun control, a move intended to emphasize Targets’ value as an “issue” film as opposed to a neutral depiction of random violence. Some critics did not buy the tacked-on message — Penelope Gilliatt wrote in the New Yorker that “Targets is supposed to be a polemic film in favor of gun control, but as you watch the central maniac’s ghastly spree of sharpshooting, the repulsive thing is that you begin to look at it as if it were Julia Child slicing onions and cutting pastry on TV” — whereas others, including Roger Ebert, viewed Bogdanovich’s treatment of the shooter’s story as an interesting social critique while dismissing Karloff’s lower-stakes storyline as extraneous.

While, in retrospect, it’s a stretch to describe Targets as being a pro-gun control manifesto, Bogdanovich’s unflinching and unsettlingly plausible depiction of Bobby’s shooting spree remains compelling, particularly given the inescapable rise in mass shootings that would occur in the decades to come. The grim increase of the film’s social relevance is one clear reason why Targets looms large today; whereas the New York Times’ Howard Thompson identified Bobby’s lack of a clear motive as a fundamental flaw in 1968, Sight and Sound’s Chloe Walker noted in 2023 that “Targets treats the idea of murder needing a motive as something quaint, old-fashioned. In this new world, the randomness of the horror is what makes it so horrific.”

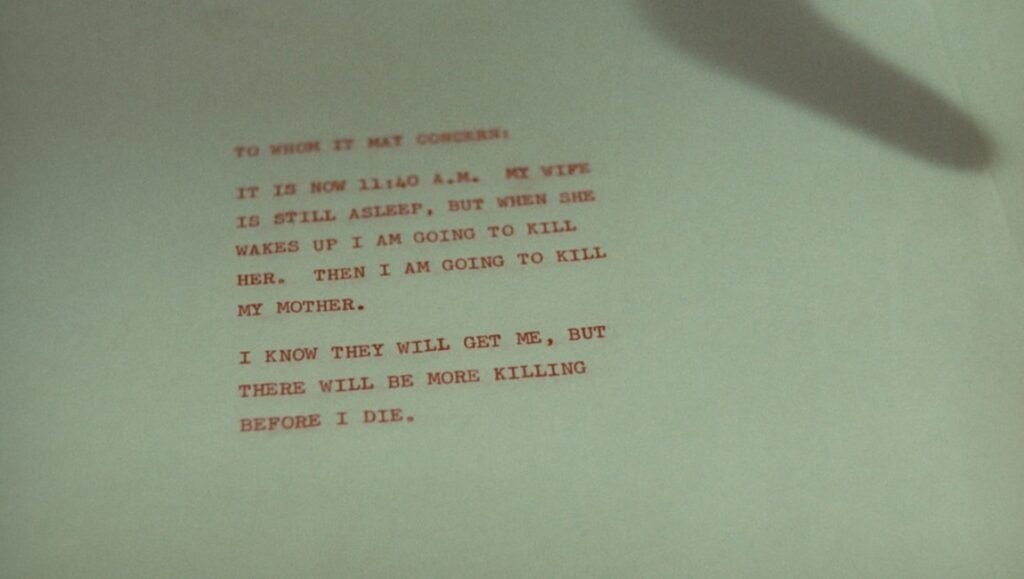

Bogdanovich does indeed dispense with any logical motive for Bobby’s actions. Aside from a vague comment Bobby makes to his distracted wife the night before the shooting —“I get funny ideas… I can’t do anything, can I?” — Bogdanovich provides no opportunities for the viewer to glean any kind of accessible interior life that may explain away his crimes. Instead, with cool clarity and disciplined camera direction, Bogdanovich follows Bobby as he purchases guns, drives on the freeway, and goes about banal routines with his parents and his wife in their suburban home. The following day, in which Bobby murders his wife, mother, and a grocery delivery boy before embarking on his spree, is shot with the same neutral distance, a tactic which marks Bobby as an unknowable object rather than an intimately familiar subject. Bogdanovich’s collaborators contribute heavily to the sense of discomfiting distance he develops. László Kovács’ cinematography is as chilly and static as the emotionally vacuous Bobby, and as designed by Polly Platt, the tacky, impeccably color-coordinated house of Bobby’s parents is so manicured as to appear shellacked, rendering its inhabitants lifeless by association.

As engrossing and perceptive as Bobby’s story is, Karloff’s half of the film is essential to Targets’ power and suggests the preoccupations that would emerge in Bogdanovich’s later work. Bogdanovich, at the time, was well-known for his inveterate advocacy for the filmmakers of earlier generations, and once he moved to Los Angeles, he cultivated deep social connections with older directors like Howard Hawks and Orson Welles — in an essay for Targets’ release in the Criterion Collection, Adam Nayman aptly deemed Bogdanovich “the old soul of New Hollywood.”

Sammy, then, is a proxy for Bogdanovich himself. When he shows up at Orlok’s hotel room to beg him to sign on to his new film, he becomes distracted by Howard Hawks’ 1931 film The Criminal Code, which featured Karloff in a supporting role, on television, and remarks that “all the good movies have been made.” Whereas Orlok calls himself a “museum piece” and a “dinosaur,” Sammy, like Bogdanovich, views him as an emissary from a better time, an age marked by great cinematic artistry to which the turbulent present cannot measure up. In this spirit of reverence, Bogdanovich gives Karloff a showcase moment, in which he tells the eerie, ancient story of the “Appointment in Samarra” as the camera inches closer to his face, ending in a close-up that includes flashes of direct address. It is an absorbing performance that exceeds the frame of Targets, functioning as a tribute to Karloff’s considerable talent and towering legacy beyond the film’s narrative scope. Bogdanovich would go on to make a series of films that pay explicit homage to classic Hollywood’s genres and personalities, most famously What’s Up, Doc? and Paper Moon, and the seeds of his larger cinematic corpus were planted in the open admiration of Karloff that imbues Targets.

The unabashed nostalgia and reverence for his cinematic elders that Bogdanovich shows in Targets is clear, yet has been comparatively under-discussed in comparison to the genuinely jarring perceptiveness with which Bogdanovich frames the permeation of violence into public life. The interplay between nostalgia and contemporary critique, though, is why Targets remains such a fascinating cinematic object. In its culminating scene, Orlok physically overpowers Bobby, while his movie self on the drive-in screen towers over them both. As Bobby cowers and whimpers, Orlok looks down on him with disdain, asking: “Is that who I was afraid of?” This scene — where a figure of artful dignity from the past dominates the callous violence of the present — presages the climax of Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, in which a washed-up Western star literally torches the Manson family before they can reach the Tate-Polanski house on Cielo Drive. Tarantino is a documented fan of Targets, writing that “Targets is about what happens when the boy can fight the monster no longer. When the monster wins. When the monster breaks free, takes control, and wreaks bloody havoc on all who cross its path.” Bogdanovich, the stalwart nostalgist, identified the signature monster of contemporary life with ruthless precision, and found him wanting when compared to the most iconic monster of cinema’s past.

Comments are closed.