The House with Laughing Windows (1976) — Pupi Avati

Giallo, the popular genre of Italian horror, can in truth be many things, though it tends to evoke certain signifiers: a gloved killer, hyperstylized visuals, deep eroticism. In Pupi Avati’s The House with Laughing Windows, soon to be released by Arrow Video in a 4K restoration and which screened for the first time at Fantasia, small elements of those genre hallmarks arise, but there is also something more idiosyncratic, and dark, happening. A man (Lino Capolicchio) is hired to restore an old fresco at a church in the countryside, and it turns out the original artwork was done by a psychotic “death artist,” a man who was obsessed with painting people at the moment of their death. As you might expect, people begin to die, and it seems the old artist, presumed dead, may be alive and well and carrying on his macabre work. It is surely a lurid story, but Avati’s aesthetic instincts are slower and more measured in how they develop dread and unease when compared to contemporaries like Dario Argento or Mario Bava. Well, the ending contains a pulpy twist that wouldn’t be out of place in those films, but the rest is more peculiar, as the film plays smartly on this outsider character coming in to a strange village with its stranger people and their stranger-still rituals, traditions, and histories. As he uncovers bits and pieces of the mystery, very little continues to make any sense, bizarre tangents are indulged, and moments seemingly latent with meaning remain somehow out of reach. A shocking answer of sorts finally arrives at the end, and yet nothing feels resolved. This is giallo at its most confounding, and troubling.

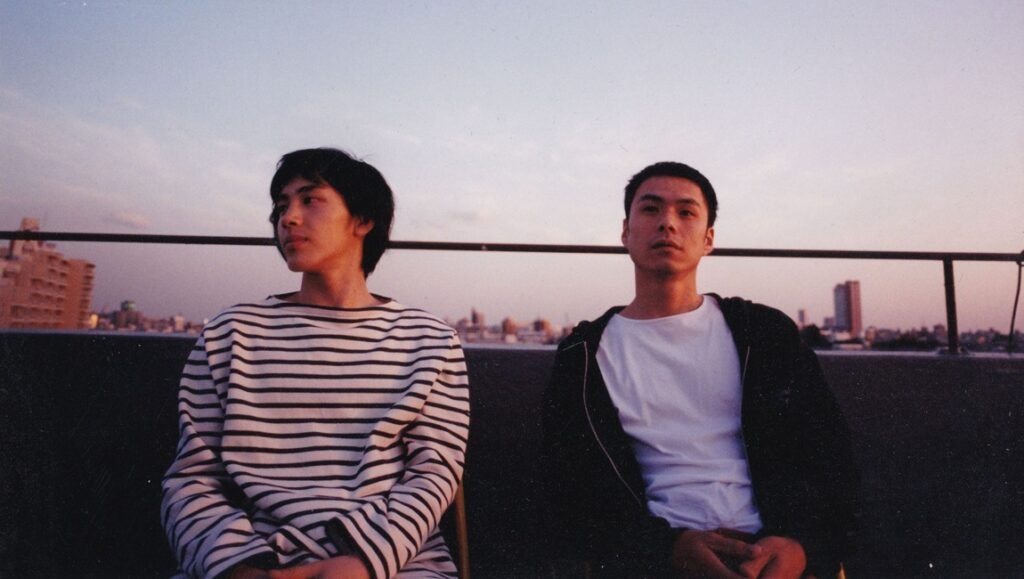

Looking for an Angel (1999) — Akihiro Suzuki

The most unexpected gem from this year’s Fantasia Festival for this writer was Akihiro Suzuki’s 60-minute experiment in early digital cinema. Telling the scattered story of a young porn actor who winds up dead and how his friends seek to remember and memorialize him, the film makes thrilling use of the rough format and equipment to draw out the blurring and beauty of memory, identity, and desire through various characters. This is, in some direct ways, a melancholic portrait of Japanese youth at the end of the 20th century, adrift in that moment’s unique ennui. It’s also an honest depiction of queer culture at the time, as Suzuki again leverages the digital amateur-ish look of pixelated sheen to provide an earned authenticity to an otherwise disjointed and near-surreal mixture of moods and environments. These are clearly constructed characters, but this world has just as clearly been keenly observed and recreated with a shockingly vulnerable intimacy. After barely an hour goes by, the effect is staggering.

Hostile Takeover (1988) & Pinball Summer (1980) — George Mihalka

The Hungarian-Canadian filmmaker George Mihalka was honoured at this year’s Fantasia Festival with the Canadian Trailblazer Award, and while his best-known film remains the original My Bloody Valentine (1981), audiences were instead treated to two very different, and very fun, films: his debut, the teen sex comedy Pinball Summer, and the hostage comedy Hostile Takeover (also known as Office Party). The former is, admittedly, wildly horny, but unlike other examples of the era (like the also-Canadian Porky’s), there’s something more endearing about most of these characters, who are generally less simply lecherous and more exuberantly young, dumb, and, well, you know the rest. Moreover, every needle drop is a banger, the plot makes very little sense, and it’s full of ’50s-via-’80s nostalgia trips. The latter film, then, is a more sophisticated satire on, yes, life under capitalism, but it’s way more fun in execution than that might sound. A man, played by the great David Warner, takes three of his co-workers hostage, refuses to explain his motivations, and lets things turn into a bizarre hangout sleepover that nevertheless has the threat of violence hanging over it. In the end, it comes to feel like a cheeky treatise on the very concept of power, and it remains admirably vague about what Warner’s character hoped to achieve, beyond a sliver of control. It’s a film that seems destined to be rediscovered by a newly appreciative audience.

Noroi: The Curse (2005) — Koji Shiraishi

For anyone interested in found footage horror, there are certain examples about which you hear: this is the big one. It’s a subgenre and a stylish formal approach that can be, in this humble writer’s opinion, extremely hit or miss, and so it’s always worth taking these recommendations with a grain of salt. Even so, Noroi: The Curse has long stood out with near-unanimous praise decrying it as singularly terrifying, an object vibrating with such otherworldly and unnatural horror that you almost believe it’s real. Most surprising, then, under the strain of such exaggerated praise, is that for the most part, it impossibly lives up to the hype. Early on, very little seems to separate Noroi from any number of other faux-documentary films of this ilk, as a mystery unfolds and seemingly unrelated phenomena occur and rhyme. This is part of its unique and expert handling of material, because it works not only as an accumulation of information but of extreme dread, and especially because the more we find out, the less there is to understand. This is an evil that appears to be beyond human comprehension. Like the best horror films, then, Noroi builds and builds until it feels overwhelming, and it’s a genuine relief once the credits roll.

A Chinese Ghost Story III (1991) — Tony Ching Siu-Tung

Following Fantasia’s screenings of the first two Chinese Ghost Story films in 2023 and 2024, the trilogy comes to an end with this loose sequel, as we leave behind almost every character from the first two, fast-forward 100 years, and hangout instead with a young Tony Leung as a monk trying really hard to remain abstinent despite female ghosts crawling all over him. For the most part, III feels like a rehash of the series’ first two entries, especially the second (which appears to have been filmed back-to-back with this one), even as Leung adds a lot of energy and the practical effects remain inventive and top-notch. There are discernible attempts to up the ante, particularly in the film’s explosive climax, but it’s impossible to not endure and acknowledge the feeling of diminishing returns. Such an assessment is too roundly negative, however: even under these circumstances, there is camerawork here that absolutely boggles the mind, images that you will never come close to seeing anywhere else, and a dedication to pure entertainment that is endlessly endearing. This writer would have gratefully and graciously watched a fourth entry at next year’s festival.

Published as part of Fantasia Fest 2025 — Dispatch 5.

Comments are closed.