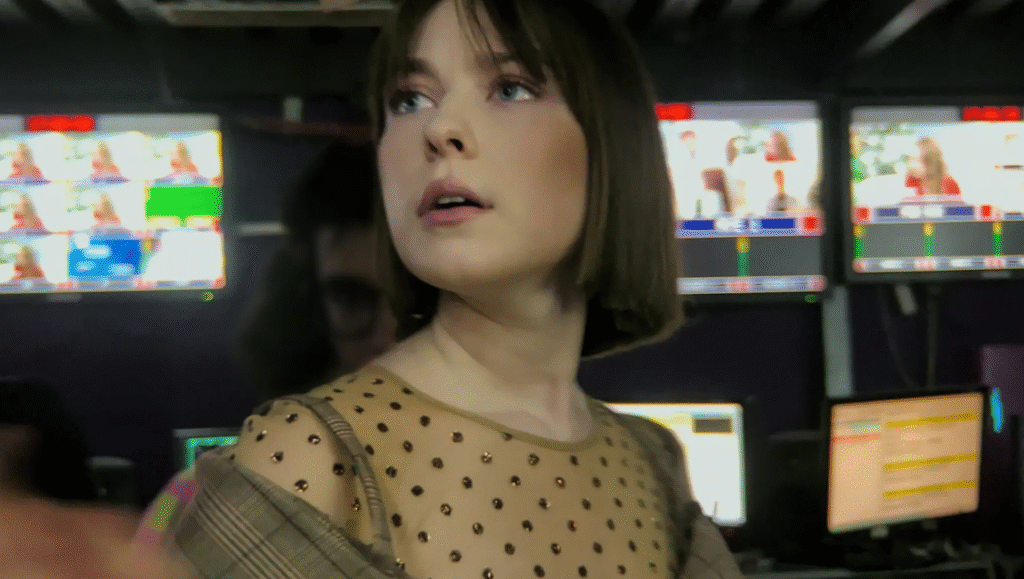

It’s always fortuitous for a documentary filmmaker to find themselves able to capture seismic historical shifts as they are happening. But of course, this is a double-edged sword. Sometimes those events are felicitous, such as the Maidan Revolution in Ukraine that unfolded around Sergei Loznitsa’s cameras. In other instances, the filmmaker is on the ground watching as the walls close in. That is very much the case with Julia Loktev’s remarkable five-hour film My Undesirable Friends: Part One — Last Air in Moscow. In it, Loktev shows us the tenuous lives and existence of opposition journalists in Russia, many of whom have been declared “foreign agents” by Putin’s government. This essentially places them in a special category of citizenship, wherein every public statement they make, every social media post and written publication, must be explicitly marked as not being from a “real” (read: pro-Putin) Russian citizen.

Over the course of My Undesirable Friends, we watch as these journalists’ lives go from complicated – censorship, surveillance, endless paperwork – to utterly untenable. Once the full-scale invasion of Ukraine begins on February 24, 2022, Russian authorities go into lockdown mode, and the young women working for opposition media outlets are forced to flee the country or face arrest. Loktev shows us the specific mechanisms by which grinding but tolerable authoritarian rule rapidly becomes all-encompassing fascism.

It’s inevitable that the broader release of My Undesirable Friends (which opens at New York’s Film Forum on August 15) will stoke comparisons with the United States’ speedrun into lawlessness under Trump and the GOP. But then, Putin has been at this much longer, and has a steadiness of vision that, for better or worse, the addled Trump tends to lack. My Desirable Friends, then, may offer a peak into a future that our nation may still be able to avoid.

I spoke with Loktev on August 4.

Michael Sicinski: This film world premiered at the New York Film Festival last October. Obviously, a lot has happened around the world since then. And one of the things that occurred to me while watching was that it’s inevitable to see parallels to what Trump is doing in the U.S. But I also realized that making those parallels may disguise or occlude as much as it might reveal. So I was wondering if you had thoughts about how specific what Putin is doing is to Russian politics and to what extent it might tell us things more broadly about the march of authoritarianism around the world.

Julia Loktev: Yeah, how the film is seen has definitely shifted so much since October and it’s startling, because it did premiere last October and I’m curious how it’ll be written about, now versus then. And even between then and February, at the Berlinale, you could see the difference because a lot of it still felt really far away. I mean, it was maybe coming for us in October, like maybe in the distance. The Russia the film depicts still feels like somewhere far away.

MS: I mean, when it premiered at NYFF, that was before the U.S. election.

JL: Right, we had hope, like, it might be coming this way, but hopefully not. And now I think people are seeing so many parallels between what happened in Russia and the U.S. And of course, there are always specifics. We can talk about the differences, whether we’re talking about Hungary, Turkey, Iran, Russia, India, the U.S., et cetera. Exactly. You know, we can go down the authoritarian rabbit hole. But possibly what’s more interesting, I think, and more instructive is seeing the parallels, and seeing how much of what is in the film resonates now with American audiences. I think we’re living through something new here. This hasn’t happened to us before. We don’t know how to feel about it. We don’t know what it feels like. We’re disoriented. We’re confused. We’re looking around. We’re going like, you know what? My neighborhood looks really nice. Everything is super lovely. Cafes are full. The world looks normal. And yet awful things are happening. And how do I process that?

And I think the film is a way of approaching that. Yes, this is what it looks like to live under an authoritarian regime. This is how things happen. Sometimes they happen slowly and then they happen really quickly. And there were a lot of things that happened during the filming that seemed very far away even when I was filming them. You know, a university dean being arrested. One of my characters saying I was in the presidential press pool until the president decided to handpick the presidential press pool. All these things felt like stuff that happens “over there.” And of course, now I’m looking at it going, no, actually it’s very close. For example, we should be paying close attention to the targeting of the media that’s happening now. Because it starts with funding. It starts with lawsuits. It starts with economic pressure. It starts with legal pressure. It doesn’t start immediately with searches and arrests the way we imagine it.

I think there’s this crucial line in the film, something that didn’t seem that important when I was filming it. But now it keeps coming back to me. One of the journalists in the film interviews this anthropologist and she’s talking to her about how it’s so strange for her to live in contemporary Russia, because on the one hand, there’s cafes and round the clock delivery and life seems to be great for everyone. And meanwhile, a friend of hers’ fiancé is in jail on treason charges. Journalists are living in terror that they’re going to be searched or arrested. And this is all happening at the same time. And she says, I don’t know how to put this together in my head. And she mentions in another scene also, saying here we are hanging out, you know, drinking nice wine, having a nice time. And all around us, we’re feeling like we’re screwed. And how do you make sense of that moment?

But in the interview that she conducts with the anthropologist, the anthropologist says, well, you know, we’re used to this idea that an authoritarian society looks like V for Vendetta. And it’s grim and everyone has this sense of oppression. But in fact, living under an authoritarian society looks pretty nice to most people.

MS: I think it was Ksenia who made the comment, toward the end of chapter five, “I knew things were happening, but I thought there would be more time.” The film definitely gives you this sense of the proverbial frog in the boiling water. You know things are moving in a bad direction, but then the Ukraine war seems to be the accelerationist moment when it kicks into high gear.

JL: Exactly, you boil the frog slowly until suddenly like the pot boils over. And for Russian independent journalists and civil society in general, when would that moment be? It was very clear in the film, I got to capture everyone in the months before the invasion when they didn’t know there would be a full-scale war. Obviously there’s been a war for almost eight years by that point, of a scale that people found acceptable. But they all kept working and they all kept trying to figure out how long can we keep working here? How can we work living in this country that has a government which we oppose, which is doing horrific things? And how long do we keep trying to fight for this society and make it better? They stay until the moment where it becomes absolutely clear to them, in the first week of the full-scale invasion, that if you don’t leave the country, you’re going to end up in jail. And that’s when they finally make the choice to leave.

And for me, it was only by sheer luck that I happened to start this film about journalists being named foreign agents. So then I got to capture all of these events as they unfolded in real time. It was incredibly lucky for me as a director. I mean, it feels strange to say that given the horrors of the war, but I think, as an act of witnessing history and also taking viewers into this environment of what it feels like to live under an authoritarian regime and try to fight it? And what does it feel like to try to figure out, are you going to the office or are you going to the airport in five hours? And what do you take? You go home, you pack a carry-on suitcase and you’re leaving your country for possibly decades. What does that feel like when to be in that moment? For me it was incredible to get to capture these super smart, funny, amazing women going through this. Of course, I’m sorry they had to go through.

MS: That leads to another question. Obviously most of the journalists you profile are women, and there could be lots of different reasons for that. I don’t know if that speaks to the gender composition of the Russian anti-Putin left, or maybe male journalists had already been imprisoned by that point. Could you maybe speak to the gender composition of TV Rain and, resultingly, the film?

JL: It’s not just TV Rain. A lot of the film features TV Rain, but there’s other media in the film, such as Yelena Kostyuchenko, Novaya Gazeta, and the “Hello, You’re a Foreign Agent” podcast. But, yeah, most newsrooms, strangely, there were a lot of women. I mean, I don’t know if it’s the composition of the Russian opposition, but it is the composition of newsrooms. So there was just a very high percentage of women. Often there would be a male editor. But in the newsrooms it really was predominantly women, a lot of young women journalists.

And also, I have to film people I love. I have to film people that I click with, that let us in and let you in as a viewer, that are funny, that are sharp. But I didn’t set out to make a film about mostly women. There are definitely a couple of men. And I always joke that, of course, if I made a film about journalists where there was like, you know, mostly men and a couple of women, nobody would ever ask, why is it mostly men and a couple of women? Like that question cannot cross anyone’s mind even.

MS: Well, yes, of course. But I do think your film presents this radically different point of view because a lot the Western media representation of Putin’s Russia — Adam Curtis’ recent documentaries are a good example — tends to have this masculinist bent, where it’s Putin restoring this ideology of masculinity, a lot of the same stuff you hear about Trump in America. Men feeling somehow marginalized and falling into this new fascist identity that overcomes alienation. Eduard Limonov and his legacy is part of that, I think. But what you show in the film really seems to be a real antidote to that, whether intended or not.

JL: Well, a lot of people see the film and they’re like, I’ve never seen Russians like this. You know, because they’re used to seeing kind of older men. And I mean, that’s often the content of political documentaries in general. You know — they’re big, important men. And this film isn’t that. Like, these are girls that you could meet in Brooklyn. I would say, you know, they could be like your friends, but they’re probably more like your kids’ friends because they’re all incredibly young. A lot of them are Gen Z. And they watch Emily in Paris. They refer to Gossip Girl. They’re constantly referring to Harry Potter.

MS: Yeah, it was really kind of interesting how Harry Potter is this major touchstone.

JL: Harry Potter is huge in Russia. And so for a lot of these characters, Harry Potter is a framework for understanding good and evil and a framework for understanding Putin’s Russia. So they feel like people you know. And I think that’s what’s so important as you’re living through this historic, awful moment in this authoritarian country, is that you’re with a bunch of very sharp, very funny young women who seem so familiar.

MS: Right. Like you said, if it was mainly men, no one would question that. But maybe that speaks to the stereotype of where power lays, right? That women working independently and informing the public is not immediately understood as something truly dangerous until later, when it has to be squashed. Authoritarianism is often very lazy, right? It’s not going to flex its muscle until it absolutely has to.

JL: I disagree. I think authoritarianism is quite diligent. I don’t think it’s lazy at all. I mean, if you look at, for example, in our country, what’s happening in the U.S. now. It is [the regime] figuring out every legal angle, every possible way to assert its agenda. I mean, I look at university settlements now. I had this conversation with a friend who teaches at Brown. And, the big news story is a $50 million settlement. You think, okay, not so bad, right? But then you read about what Brown actually agrees to do. Change the language, using the definitions of gender of the Trump administration. Questions about DEI, all of these small compromises that are in the fine print. This professor literally sent me the agreement or the appropriate sections of the agreement that Brown made and, well, the devil is in the details. Authoritarianism is extremely bureaucratic and diligent.

MS: No, that’s true. What we see in the film is kind of like you said, starting with the “foreign agent” idea. It really seems like the initial push on the part of the regime is to make participation in the opposition just a day-to-day hassle. It’s about having to put “the fuckery” on your Instagram post of a sunset, just this constant nagging. But I guess the question is, at what point does that insistence on bureaucratic rigmarole and legalese then turn to people being locked up and pulled off the street?

JL: It’s part and parcel of the same thing. But I think that’s important to go back and kind of explain what “the fuckery” is. The fuckery is this statement that all these journalists who had been declared foreign agents had to put in front of everything. And it said, “the following information has been brought to you by a source that is a mass media foreign agent, or an entity operating with Russia on behalf of a foreign agent…” I mean, it’s been a while since I’ve quoted it… “carrying out the function of a foreign agent.”

So basically, it was this long paragraph of legalese saying that this material is by a foreign agent. So, for example, in this interview, if you were declared a foreign agent, you would have this paragraph that would be in a bigger font than anything else. At the start of this interview, there would be this paragraph in all caps, saying that you’re reading something brought to you by a foreign agent, except in very legal terms. And let’s say I was a foreign agent. You would then have to say, here we are talking to Julia Loktev, who we must say is a foreign agent. Because if you didn’t say I was a foreign agent, you could get fined and your outlet eventually closed.

And you’re right that at first it just makes work impossible. Or not impossible, but difficult. Let’s say it’s not impossible because all of these people kept working. It takes money. They’re fining you. It takes time. A huge amount of your energy is dedicated to this fulfillment of these constantly shifting goalposts. You know, “is this okay to say? Is that okay to say?” And look at what’s happening with civil society in the U.S. and NGOs, everybody having to comb through their language to figure it out. Like, I mean, I was reading recently about like the directive to National Parks to take out any references to DEI, and everyone was looking at descriptions of historical events, or climate change for that matter, and doubting themselves. Like, is this okay to say? And it constantly puts you in this state of fear.

MS: Exactly. It creates a chilling effect.

JL: Yeah, but it’s also the unpredictability. For example, when Russia started naming journalists as foreign agents, it didn’t start with the most important, most obvious ones. It seemed completely randomly. So it has to give you the feeling that this could happen to you, no matter how important or unimportant you are. You constantly have to exist in this state of fear. It could be me. That is a huge part of how these regimes work. It’s a sense of constant possibility, constant threat, and just not exactly knowing what’s okay, what’s not okay.

And certainly we see that in terms of how the Trump regime is operating. It’s about making a few high-profile examples so that everyone else will fall in line. And as this is done, people claim, “we’re just following the law here, we’re just carrying out the law,” and I think a lot of us are… we’re not used to this approach. We’re confused, and I think the film hopefully gives people a way of processing this.

I like to tell this one story. We have a screening club, where every time I edit a chapter I gather a group of people at my house and I want to see like, is it working? You know, because I want the film to work for people who really can only name Putin, maybe Navalny. Maybe they can’t name a single Russian woman. The goal is, you don’t necessarily have to be interested in Russia to watch this film. And so I gathered this club for the first time when we edited Chapter One at my house. And, it being New York, a lot of people were from somewhere else. People from Iran. or friends who grew up under the dictatorship in Argentina, China, and then some people born and raised, I don’t know, in Ohio. And when we first showed Chapter One for the first time, a while back, long before Trump was reelected, the people who lived elsewhere, under the dictatorship in Argentina or in Iran said, “oh my God, we’ve never seen anything that shows in such a visceral, everyday life way what it feels like to live under authoritarianism. The contradictions, and how there’s so much life around it and life goes on, and yet all these awful things are happening.”

And then the other half of the room said, “well, we don’t quite understand. Why exactly were these particular people named foreign agents? You have to explain that much more clearly in the film and explain how this works.” And then the half of the room who had experienced authoritarianism started yelling at them and they said, “that is how it works. If you understand how it works, it doesn’t work.” And it strikes me that we would not be having this conversation at all in the same way today in August of 2025. I want my innocence back.

MS: Indeed! As you’ve said, people in the U.S. don’t really have the same kind of framework for understanding this. But what’s happening in My Undesirable Friends, we see people who have the Soviet Union in living memory. There has to be some sense of familiarity. But then, in as much as you see older folks in the film, many of them are like the older woman who was saying, “Putin’s right. Arrest them all.” So does the fact that in a way this is kind of a replay, like make it more comforting for some and more terrifying for others?

JL: Maybe for some of the older people, yes. Meanwhile, most of our characters have no memory of the Soviet Union. Some of them were in first grade when Putin came to power. They’ve never lived in the Soviet Union. I mean, what they have lived under is just endless, endless, eternal Putin. They’ve never really known as adults anything else. I mean, they talk about this period of Medvedev, who’s now become Putin’s barking dog, right. But that brief period seemed like relative freedom. I mean, he said beautiful quotes like, “freedom is better than unfreedom.”

MS: How beautifully Orwellian.

JL: Right? But, you know, at least there was that idea. But for most of them, Putin has been their entire lives.

And yet, still things have changed. That’s really important, the non-inevitability of this, and how it crept, crept, crept, and then it went into overdrive.

MS: Yes. And regarding the ever-presence of Putin in their lives, I mean, one of the underlying ideas of authoritarianism is, it’s not just about the present, but it’s about the future. Trying to curtail any vision of anything different. And when you have folks who have known nothing but Putin, how were they able to hold on to a vision of life after Putin?

JL: I don’t know if they can imagine what that will be, but I think it’s incredibly inspiring that all of them continue to fight for it. Even now in exile, all the people I filmed are working as journalists, working toward the good of this country to which they may not return to for decades. I find that incredibly, incredibly inspiring, actually. How do you continue to fight when the fight feels lost? And even though this is a film about terrible things happening, I actually appreciate hanging out with the characters and being with them and seeing their humor and their resilience

MS: There’s a lot of joy in the film.

JL: Their joy is a form of resistance. I think that’s really important, the joy and humor and energy. I find it all tremendously inspiring.

MS: You’ve already got Part Two underway, is that correct?

JL: I just finished. It’s probably also going to be, I think, five chapters. I just finished editing the third of those five. The first five chapters of My Undesirable Friend take place in this kind of now-unimaginable world of oppositional pre-war Russia, which really doesn’t exist anymore. Everyone’s in exile and the film ends in the first week of the full-scale war in Ukraine as everyone flees the country. And then the second half picks up two days later, after everyone has fled. I stayed in Russia filming until every single one of my characters left the country, and then I spent one day uploading footage and joined them at the next stop, Istanbul, and just kept filming as people moved from country to country.

That’s also incredible because obviously different societies have gone through a mass exodus. One million people have left Russia since the start of the full-scale war. That’s a huge thing. And capturing that in real time, how it feels in those first days when everyone’s disoriented, having bought the first ticket they could find, to the only places tickets were still available to. For example, you couldn’t fly to the U.S., you couldn’t fly to Europe, you could only fly to Mongolia or Istanbul, and Dubai, which nobody could afford. And what does that feel like? Yesterday, you were a journalist, you had a media outlet, and now your media has been shut down. Your country is waging a war that you oppose. And you’re moving between hostels in Istanbul. You have no idea what country you’re going to. You’re trying to figure out how to keep working. Your bank card isn’t working.

And meanwhile, you’re constantly reminding yourself, you’re actually okay, because meanwhile your country is bombing Ukrainians. And those are the people with real problems. So you’re constantly telling yourself, that’s what real problems look like. And, I mean, that’s true. Obviously, none of this is comparable to being bombed and the war crimes that Russia is committing in Ukraine.

But I got to film this in real time as people tried to figure out like, okay, how do we get a media up and running again? How do we keep reporting on this war? How do we keep telling the truth to Russians? And then again, how do you keep going when the fight seems lost and yet you have to keep going because that’s the only thing you can do morally, to keep reporting, keep telling the truth, keep fighting.

MS: One of the things that I think you see, certainly in chapters four and five, is that these are people who very much love their country. And yet their country simply doesn’t love them back. I think it might have been Sonia getting messages from angry Ukrainians, like “I hope you sleep well at night.” There’s a recognition that, no matter how hard they fight against Putin, they are somehow still implicated in the things that their nation does. How did you find that they were able to mentally negotiate that? How were they able to reconcile the fact that to the world, they still somehow represent this nation that they feel is not in any way representative of their values?

JL: Yes, I think that’s an important question. And I think that’s largely what happens in Part Two, as they attempt to struggle with all of this. It’s not easy. But I think one thing they don’t do, which always amazes me, is try to wash their hands of it or try to shirk it. In America, there’s this thing we love to say, “not my president.” Like, “I didn’t choose this. I have nothing to do with this.” They don’t do that. They talk about this as if they are part of it. They do love their country deeply. As you said, it does not generally love them back very much. I mean, many of them now have criminal cases against them. None of them can go back to Russia because they would be likely arrested. In some cases, that’s explicit. In some cases, implicit. They’ve had their parents’ homes searched. In some cases, they are constantly facing threats. And yet they do love this country and continue to work for it, for some hope of something different. And I think that’s incredible.

But nobody tries to kind of say, I have nothing to do with this. “ I’m the good kind of Russian.” You know, no one says that. One of the characters says, “you know, we’ve been making this monster for 20 years.” Even though, I must say, the woman who says “we’ve been making this monster for 20 years,” 20 years ago, she was six.

MS: Yes, like you said, these women are struggling, but also recognizing that Ukrainians have bigger problems. There’s never any of the kind of liberal navel-gazing and self-absolution that you see, like you said, with certain parts of the American liberal left. They recognize that they are in this. And also, no matter how difficult the circumstances of their departure may have been, they were the ones who could actually leave. Whereas Ksyusha’s fiancé, I assume, is still in prison. So there seems to be this kind of powerful reckoning with the privilege that they have, even as their world is crumbling around them.

JL: Yeah. I hate to quote this, but I’m going to because it’s like the first thing that came to mind. But I got a very nice email from Frederick Wiseman, which rocked my world, him complimenting me on the film. But then he said, “they’re also bloody smart.” And it’s really the thing that struck me. I mean, these women really are just so bloody smart. And some at 23, some at 26. I mean, they’re not all that young, but a lot of them sure are young. And I am amazed by just how sharp and wise they are, in between quoting Harry Potter.

MS: Yes, but then, that points to the life that they should be having, right? I think during the Q&A at the New York Film Festival, one of the women was saying, “I had my apartment, I had my cat, I drank coffee.” That’s what a 26-year-old anywhere should have the right to do, but that’s not their reality, right?

JL: Yeah, a lot of how this works is, when you’re in that kind of political situation, how do you figure that out with daily life? I think the film communicates a lot of what’s happening to them through their daily life. For example, in the apartment change between a couple of chapters, one of the characters, Sonia, who’s been declared a foreign agent, she’s 26. She’d recently moved into an apartment with her boyfriend. She can’t figure out whether to buy a couch, because she’s been declared a foreign agent. She doesn’t know if she can buy a couch because, is she going to get to stay? And then we meet her in the next chapter again, and she bought the couch. And to me there’s so much in that. That’s how we process reality, you know? The decision, “okay I think I might have a future here. I’m going to buy a sofa. I think I might be staying.” And then, of course, two months later, bye-bye sofa and hello airport.

But so much of how we experience momentous events is through these very real everyday moments. And I think that’s what I’m ultimately interested in. So it’s a strange kind of political film, because it’s not like a normal documentary where people explain the world to you in interviews. And it’s really like you’ve gone to hang out with these people and live through a lot of shit with them.

As a filmmaker, I was incredibly lucky to capture all this happening in real time through these characters that you feel like you know and love and to live through it with them. You know, that’s just sheer luck. And of course, I’m also in a kind of unique position to tell the story, which I wouldn’t have been able to otherwise. I was born in the Soviet Union, I was born in Russia, I speak unaccented, fluent Russian. You know, I miss out on some cultural references since I left at nine, but people feel at home with me in a way they wouldn’t with an outsider filmmaker coming in. But at the same time, you know, I’ve been in the States since I was nine years old.

And so I’m very much looking at the story from an outside perspective and figuring out, how do you tell this to an international audience? Because if you’re telling it really from the inside, a lot of the time, you don’t know what people don’t know. You forget what an international audience might not know. So I’m kind of looking at it as an American but also as someone who is very much an insider because of the language, so it’s this inside/outside perspective that gives the film I think that intimacy.

MS: Yes, it’s a very immersive film, and one of the things that I think adds to that is that you aren’t afraid to go long. You’re not afraid to have made a long film. And I think it really takes that amount of time to, A, get to know them, and B, to understand the situation changing around them. And the viewer has to kind of figure all of this out along with them. It’s really terrific how you don’t signpost all of these things for a non-Russian viewer.

JL: And you really are living through this historical moment with them, but of course you’re living through it in a very different way. Like you’re watching the film knowing Russia’s going to invade Ukraine. It’s not a secret, you know.

MS: Or that Navalny is going to die.

JL: Exactly. As a viewer, you know all of this. They’re constantly talking about Navalny who at the time is in prison and is this beacon who continues to be very funny, very inspiring to all of them while in prison. And because of what you the viewer knows, you’re watching all of these people hurtling toward disaster. In spite of that, people say it feels like a thriller. Which is strange because, of course, you know where this story goes. But they don’t, and so you still experience it in the moment.

MS: I think that really speaks to the power and the resilience of these subjects in the film, that even though we as viewers know that the things that they’re afraid of are in fact going to happen, it’s not a hopeless film. Even though the worst has happened and is going to continue, they still radiate hope and optimism for the viewer.

JL: I think that’s really true — it’s strangely not a hopeless film. And not, I mean, like I said, I find them incredibly inspiring. And also just they’re fun to hang out with. I filmed them now for three years, and it’s been an incredible pleasure and a joy for me to be around these people and spend time with them I just enjoy them so much because they are sharp. They are funny. I tend to say that, you know, for a film about political repression in a cold place, it’s unexpectedly warm and funny. Like you think it shouldn’t be, but it is. There’s a lot of humor. There’s a lot of joy. And that is part of the resistance, I think.

Comments are closed.