In the late 1950s, Brazilian footballer Didi introduced a new technique for kicking the ball, the so called “dry leaf.” Much like a leaf falling from a tree, shifting direction unpredictably, the ball would swerve through the air in ways impossible to anticipate. Not even the person who kicked it could say where it would land. Everything — wind, pressure, chance — played a role. And once the leaf begins to fall, there’s no stopping it, it goes where it will, carried by invisible forces.

It’s a fitting image for the cinema of Alexandre Koberidze, where fate, coincidence, and unpredictability are not only recurring themes, but guiding principles. In his films, characters often drift through the world like leaves on the wind, subject to mysterious forces beyond their understanding, yet somehow finding beauty and meaning along the way. The presence of football in his work has always been more than symbolic; it’s a space of play, chance, and deep emotion. That his new film is titled Dry Leaf is no surprise, but rather a continuation of an artistic path shaped by curiosity, wonder, and trust in the unknown.

Koberidze’s third, lengthy feature revolves around the disappearance of Lisa, a sports photographer, who vanishes without warning, leaving behind a letter asking not to be found. She was last seen photographing rural football fields in remote Georgian villages. Her father, Irakli (played by David Koberidze, Alexandre’s father), unable to accept her disappearance, sets out on a journey to find her, teaming up with Levani, Lisa’s enigmatic best friend and editor, and together they travel across the countryside, retracing her steps through quiet villages, meeting kind strangers, and speaking with children playing football along the way. What they uncover are only fragments of Lisa’s presence, traces that become increasingly elusive the further they go.

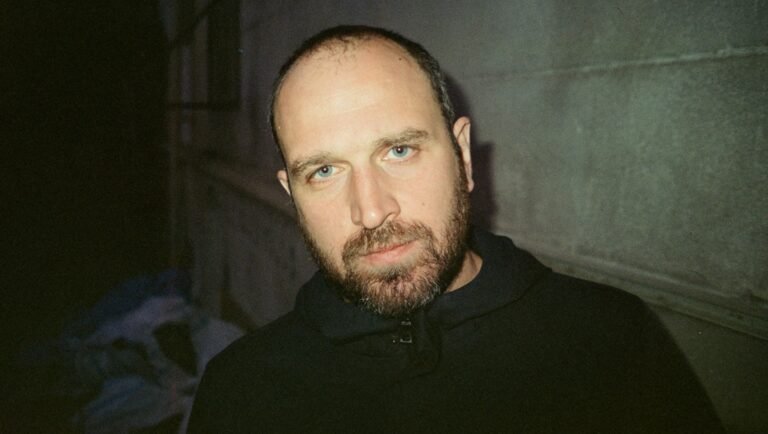

In Locarno, I had the pleasure of sitting down with Alexandre Koberidze to talk about his new film, his lifelong passion for football, what it was like to work with his family, and other elements of Dry Leaf, including the presence of “invisible” people and the way he shaped this unconventional road movie.

Omar Franini: Football has always been present in your movies. And there is also, if I can say that, an evolution in the way you implement it in your films. Because if I look at What Do We See When We Look at the Sky? and Dry Leaf, I feel there’s a different way you use the sport.

Alexandre Koberidze: I think it’s more like a feeling, about slowly understanding what is interesting for you in life. And also, while making films, realize that the things you appreciate or love in your real life, they can become part of your work, or maybe they should. For me, this wasn’t so clear in the beginning, when I first started thinking about making films. Because you can make a film about anything. And I don’t know, when you watch films, maybe you’re driven by a certain genre, or by very fictional stories that don’t have much to do with yourself. But quite soon it became clear to me that if I want to make a film that should be passionate for someone else, then I should be passionate about it myself. And maybe I should work with things that are important and dear to me. And definitely, I think football is one of those things. So, it makes sense to bring it in. And of course, once you do, it gives you a lot of possibilities… to create stories around it.

OF: You also used football for the title Dry Leaf. In Italian, we would say Foglia Morta. Was it always the title from the beginning, or is it something you realized while writing or shooting the movie?

AK: Yeah, I heard that in the 1960s there was a famous Italian player who was a master of the “dry leaf” shot. That was even before I thought of using this title for the previous film. I liked it already back then, especially because it also had that football connection. But for that earlier film, it was a title that didn’t really fit. So I thought, maybe I’ll use it next time. And now I think it really works.

OF: Differently from your previous movies, I noticed that this one is a road movie, while your previous two features were shot in cities, Tbilisi and Kutaisi to be precise. Was it something you specifically wanted, to move away from the city structure and try something else?

AK: Definitely. Because I had this feeling that in those two films, the first one was really a city portrait film. In the second one, I tried to move a bit away from that because repeating yourself is the worst thing you can do. But I didn’t quite succeed. I think I’m very fascinated by cities, so when I’m in one, it still ends up becoming a big source of inspiration. In my second film, maybe it was a bit less than in the first, but still, the city was a big part of the film. So then I thought, maybe the only way not to repeat myself a third time is simply to leave the city.

OF: Had you planned this road movie, or was it more like: I’m going to explore this area and find inspiration from whatever I encounter around me?

AK: Yeah, it was almost not planned at all. We planned to go to different regions, and maybe we had one or two places in mind that we wanted to visit. But the rest, well, we would just ask people for football fields or other places, and they would send us in this or that direction. And then the next day, it would be the same. So it was completely… Very often we didn’t know where we would end up the next day.

OF: Would you say the movie has a nostalgic view toward these places, toward the people? I personally had this nostalgic feeling, especially toward the ending, when Irakli meets this young boy who is waiting for his friends to go and play. And the boy tells him that there is no football field anymore. I wrote down this sentence because I loved it: “But if there is no football field anymore, where do you play?” — “Everywhere.” It reminded me of when I was a child, going with my friends into a field, just placing down some shirts to create goalposts. That scene really brought me back to that time.

AK: Maybe… Like, it wasn’t something I was consciously thinking about while making it. But when I see it now, I think maybe there’s something in the character, or in the tone, that brings that feeling. What I discovered during our travels is that there are not as many football fields left as I had imagined. So whenever we found one, it was on one hand amazing, but on the other hand also a bit sad, like, okay, there are fewer and fewer of them. And when we did find one, we felt we had to capture it. And maybe that’s what brings this kind of nostalgic feeling into everything.

OF: Speaking of the aesthetic, there’s a similarity to Let the Summer Never Come Again with the use of the Sony Ericsson camera. How did it feel to reuse the same technology from your first movie? Was it something you always planned?

AK: Yeah, because when I finished Let the Summer Never Come Again, I had the feeling that it was enough. I had filmed so much with that camera, and I felt like, okay, for now, it’s done. But then, after a few years, I really started to miss it. Before, I had worked so much with it, and then there was a break, and I made a film with completely different equipment. And I really, really missed it. But when I started this film, I really had to get used to it again. Because if you don’t use it for a while, you forget how pixelated it is, how different it is. Even physically, with your hands. Because for many years, I always had it with me, so your hands get used to the start-stop, the movements. I just needed some time to recover that motoric memory, but then it came back, and it was really nice.

OF: And I read that you didn’t use any artificial lights, that you were looking for a natural one. There’s a particular scene where Irakli goes to visit his aging uncle, and I really loved the colors inside the flat and just outside of it. At first, I thought: Oh, they used lights here. But then I realized, no, they were probably searching for something special. Was it difficult to wait for the right moment to capture that kind of color and lighting?

AK: We had the possibility to do that. That’s why sometimes we would go to a place, and maybe go again the next day, or just hang around and wait. Because this camera really needs the right light to make a good image. And sometimes, even if you know, okay, today is not such a good day to shoot, because you see the light won’t change, or the sky is cloudy in a particular way, then it becomes really hard to make good images. So we’d say: Okay, let’s not work today. But the good thing is, when it’s just you or maybe two more people, you have the flexibility to make that kind of decision, to say: Let’s go and come back tomorrow. When the forecast says the sun will come out, then we return.

OF: And during the movie there are a lot of invisible figures. What about that?

AK: I don’t know, it started at the beginning with a simple idea, to have one invisible character. And I was interested in how to film him, what kind of possibilities that gives, and so on. But then I thought, why only one? Because if it’s just one, it’s strange. It could appear like someone’s fantasy, or like an imaginary friend from childhood, something like that. But then I thought, what if it’s the whole world? If half of the population is invisible, then it can just become a normality in the world of the film.

OF: That’s what I actually thought at first, that these invisible figures were part of Irakli’s imagination. Especially near the ending, when he says that Levani didn’t let him drive him home, I thought maybe he was just an invented character, someone he imagined meeting.

AK: No, no, that’s one of the risks, of course, that it can be interpreted in a different way, and I’m okay with that. But in my imagination, they are really there.

OF: Dry Leaf feels like an intimate family work, in a way. You’ve already worked with your brother in your previous films, but I think this is the first time you’ve worked with your father on screen. How did that feel?

AK: It was kind of calming, I would say. Because with this kind of work, like I described, where we go somewhere and I have the freedom to say, Let’s not shoot today, we’ll shoot tomorrow, you need people who are really with you. Otherwise, if you start to feel nervous, they’ll get annoyed too. Sometimes we would go to a place, and I didn’t really know what to shoot there. I’d say, Let’s just stay here for half a day and see what happens. Maybe you read something, or just wait. And for that kind of approach, you really need people who are completely committed to what you’re doing. And I think family is something like that.

OF: How do you usually work on the music with your brother? Do you wait and create something in the editing phase? Or do you use music that already exists and then try to incorporate it into the film?

AK: It depends. In the previous film, it was more like I had some ideas about how the music could be. I used some temporary tracks in the beginning, some layout music, and I gave him some examples. Then he would compose something in that direction. But this time, I didn’t say anything. He was always there during the shooting, so he really knew what we were doing, what the mood was, and what we were looking for. He was working on his album during the filming, which wasn’t directly connected to the movie. But then the music he wrote for that album somehow became part of the film too. Because I think the mood of that traveling period, where he was working a lot on his own music, was captured in it. So it was a mix, a combination of different kinds of work.

OF: What I also love about your movie are the locations. Because they don’t feel too exotic, they feel like normal places you might just happen to visit. Was that something you were aware of? I mean, not filming in beautiful, picture-perfect spots.

AK: This was definitely something I was thinking about. We specifically avoided going to the most beautiful places in the country, to the high mountains or those spots where people usually go to take pictures. Because I saw the risk that it could become too exotic, too much like a postcard. In general, it was more interesting for me to think differently, to look for simpler, everyday places and things. To stay in those places and see what might be interesting about them. To not search for something special or extraordinary, which maybe I would have done before. Because I think in the past, I was always looking for something really striking. But this time, it was calmer in that sense.

OF: There’s also a lot of focus on animals in your film. It even feels like there’s more attention on the animals than on people.

AK: Same. Exactly the same. Because these beings are everywhere, and they’re normally quite overlooked. You don’t usually pay much attention to a cow or a sheep, because they’re just there. But somehow, it wasn’t planned at all, when I was spending time in the fields, I just felt: Maybe I should turn the camera toward them, too. Because they are interesting. This is definitely something unexplainable. I don’t know. A cow, you look into their eyes, you watch how they behave, and you can learn a lot.

OF: Also because, of course, you can’t direct animals.

AK: Exactly. You can’t do anything.

OF: Are you already working on something else at the moment?

AK: Yes. We’re preparing the next film and to hopefully shoot in about a year. It’s going to be very different from this one. Very different. I want to shoot on film this time. So I’ll be working with a cinematographer, with a bigger crew. If Dry Leaf was about finding places as they are and filming them, this one might be more about creating spaces, more about building a kind of reality, rather than looking for it. That’s interesting to me now.

OF: So, no Sony Ericsson for the moment?

AK: No. Maybe the next one.

OF: If I can, I would like to ask you something about What Do We See When We Look at the Sky? It’s about the Notti Magiche sequence. Why did you choose that song? Because I’m not really a fan of it. But every now and then, when I hear it, it reminds me of your movie. And then I think, maybe this song is good.

AK: It’s from my childhood. Like a memory. A beautiful memory from the 1990 World Cup. I was six years old, and at that age you don’t really understand much. But I saw all these people around me watching TV, talking about football. Then there was the final, and Maradona crying. It was such an emotional, beautiful time. Somehow, this song stayed with me as a memory of that big passion.

OF: In that sequence, you have all these children playing in slow motion. I feel like you really capture the cinematic feeling of the sport. Because when we watch football, or other sports, we don’t just watch the game. The way it’s directed or how replays or slow motion are filmed add something extra. But at the same time, it’s a completely different experience from seeing the game live.

AK: I think [that scene] was quite inspired by the music video of the song. Because it has these very passionate moments. If you watch it, you’ll see these beautiful shots of the coaches, the most emotional moments cut together. It’s really beautiful.

OF: I would like to ask you one last question. How are you feeling, being here at the festival? Are you satisfied with how the movie has been received?

AK: I feel like this was really the best place for us to come, to have the premiere. I’m super thankful for the opportunity. We are happy here.

Comments are closed.