“So it returns. Think you’re escaping and run into yourself. Longest way round is the shortest way home.” — James Joyce, Ulysses

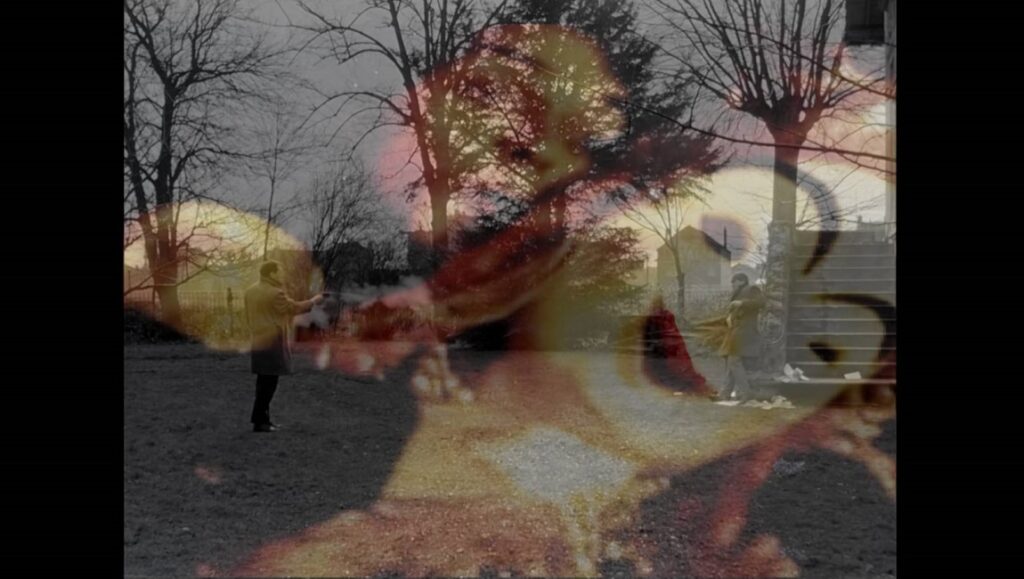

As the second part of Jean-Luc Godard’s Scénarios begins, you may feel your stomach turn. We move from a part one called “DNA, foundational elements” to a second titled “MRI, Odyssey,” and two minutes in find an exact repetition of the first — except, of course, for the added sound of what we imagine is the MRI machine. So we put two and two together. The journey that is our life (the Odyssey) is merely a reenactment of an already existing script (the DNA). What else could he be telling us? Our life’s journey is a painstaking probing into ourselves — hence the MRI — but our findings are piffling: we look inside, behind the mask, and see nothing but a black void.

For these first two minutes, the exact same movie repeated, with the added disturbance of the beeping and buzzing of the medical imaging machine, as if to wake us up in case we were beginning to feel drowsy. There’s just enough space left between each new buzz for us to get startled again at every one of its occurrences. The teacher tried telling us nicely, we didn’t pay much attention, and so now he reverts to more aggressive methods. Soon, we realize what he is telling us: there’s no escaping what’s inside us.

Our initial shock overcome, we are relieved to soon notice bigger changes. Unfortunately, they lead us to even harsher conclusions. If the MRI machine keeps at work while we see image upon image of war and killing, what else could Godard be getting at if not the point that violence is ingrained in humanity? Again, this idea, to which we had been introduced in The Image Book (and maybe even earlier, in Notre Musique), of war as a natural phenomenon: pessimistic. But after all, can we be surprised that the old man who chose to end his life wasn’t very hopeful about humanity? And a few months before his passing, hadn’t we read, in his last interview, given to French newspaper Mediapart, an undeniable avowal of defeat? “I don’t find myself interesting,” he said.

Maybe when you first heard news of his death, you for some reason decided not to read any further into it, actively avoided doing it in fact — what is there to learn you thought, a dead man is a dead man — and it was only a whole week later that you accidentally laid eyes on a report and found out that the cause of his death was assisted suicide. Everywhere, “Master of cinema,” “nouvelle vague”, “dead at 91”… and all the while you kept thinking about that last interview. “I don’t find myself interesting. For a long time I did.” And maybe at this point, you felt your stomach turn. How hopeless must this 91-year-old man have been to decide to end it all when he was already so close to the finish line? Reason may tell you it was because he was sick, in pain, but it doesn’t matter: that unease you felt doesn’t seem to go away. Then two years later you watch his last movie, and after a first half through which you remained largely unmoved, all of a sudden you receive the same shock all over again.

What teaching! Life is a lot of trouble for nothing? Everything shall be in vain? Maybe deep down we all know it, but it isn’t very polite to go around saying it out loud. Even worse: human nature is essentially flawed? War and murder are in our DNA? And then, all these masks. The camera pushes in on one of them, and underneath it we see nothing but that unavoidable void. Are we empty vessels, blindly acting our parts, running toward our deaths like Anna Magnani in Rome Open City? Against a picture of a man holding a doll is superimposed a shot from one of Godard’s early movies, the story of which you already don’t remember: two men, face to face, shooting at each other, one walking forward, the other backward; unable to distinguish them, you have the impression of seeing a man shoot at his own reflection in the mirror. The man with the doll gives way to an old man walking through the desert: slowed down to match the speed of our gunfighters, he disappears at the exact moment when the last, decisive shot is fired. One man receives the bullet and drops dead; the other, who fired, drops dead just the same. Just before his body hits the ground (for the last time, forever), he sees “a mythical bird that never steps on the ground.” And one face: “Arthur’s last thought was dedicated to the face of Odile.”

Then Godard shows up himself. We already knew this was going to happen since ARTE, full of explanations, dates, and precisions, had already told us. (Is it that they were ashamed of such a bare movie and felt the need to complete it somehow? Or were they simply afraid we wouldn’t get any of it otherwise?) He sits in a hospital bed a day before his scheduled death. He writes in a notebook something he has memorized, all the while reading it out loud. It’s the same text we had heard at the end of the first part: hearing it again, we begin to understand it better. A white horse is not a white horse? Yes. Not a surprise coming from this man who spent his entire career destroying identities, always making a point, in every situation, of breaking apart established knowledge to show everything that hides inside of it. The identity is not the essence, but rather just one particular perspective: so we look around and see a chain of infinite associations.

Godard was never an essentialist — quite the opposite. Then why all this talk of DNA and “foundational elements”? We should never be quick to judge. Maybe he does show us a fixed, immovable state of things, but it’s only so he can break it apart afterwards. Because the fact is, as soon as he makes that little, unassuming mistake in the middle of his reading, and has to start a sentence over, then everything can start over. If it were all pre-determined, then how could the actor jumble his lines? Reality is greater than any script, and it laughs at our principle of non-contradiction: the wind blows and all our constructions fall into pieces. “Everyone thinks two plus two is four,” goes another of his favorite quotes, “but they forget the speed of the wind.” As long as there is the possibility of opening your mouth and committing an error, then none of our additions and identities will be completed. And everything can start over.

It has been noted how much Godard’s last movie resembles Jean-Marie Straub’s (La France contre les Robots, from 2018) in structure: both are diptychs with mirrored halves; both share an artisanal, homemade quality that makes us think of a schoolboy’s notebook open on the kitchen table, one that when we go look at it, has the same exercise repeated on both pages. But we can go one step further and observe how much they resemble each other in their conclusions: they are both unashamed paeans of freedom. If a white horse is not a white horse — and it isn’t — then nothing is decided; if a white horse is not a white horse, that means we can go against the script, the DNA. And our hopes remain.

So are we really going to start decrying the fact of his old age? Are we really going to consider these posthumous movies from the perspective of their troubled productions — as ARTE seems to want us to — when in fact Godard’s modus operandi has always been to take concrete situations and incorporate them into his thinking and his movies? Nothing has changed. Godard employs his old age, and maybe even a hint of senility, as instruments of his movie. And he doesn’t complain. ARTE feels the need to package Scénarios alongside L’histoire de “Scénario”? They might as well do the same with Contempt. Wasn’t the starting point of Breathless precisely the impossibility of making a B-movie in the ’60s? And wasn’t Contempt’s the impossibility of making a Golden Age Hollywood studio picture? (Let’s not forget that the director wanted Kim Novak for the part given to Bardot.) And even earlier: wasn’t his interest in cinema directly related to this practical side of the camera, which once turned on films whatever is in front of it? Young, he had wanted to write a novel and couldn’t: the blank page made him anxious, and unable to write whatever he wanted on it, thus found it all felt arbitrary. What he needed was documentary. When in front of you, instead of a blank page, there is a concrete state of things — reality — and so you don’t then have to worry about starting lines.

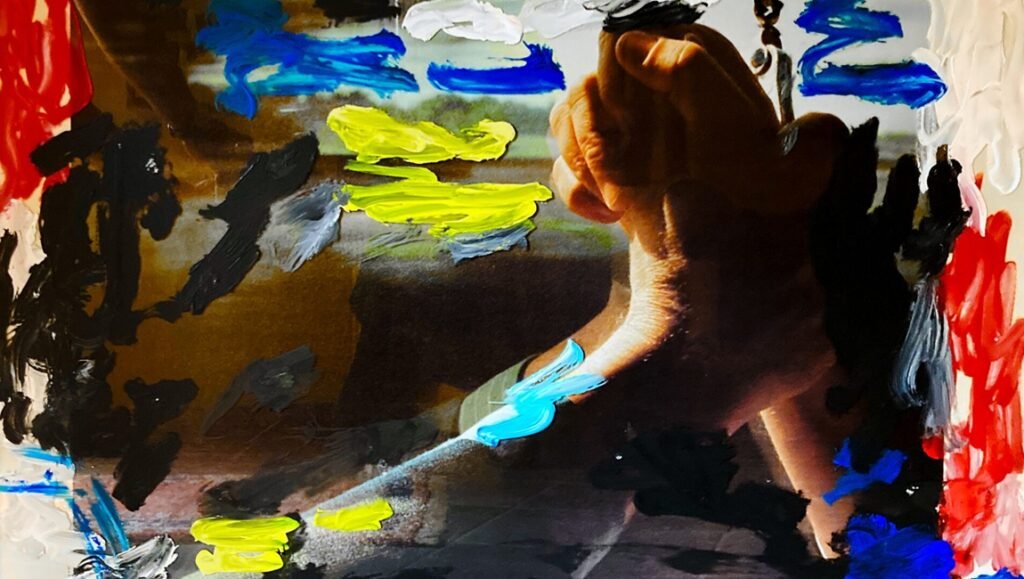

Aged as he was, Godard couldn’t work editing software by himself, so he turned to pen and paper. And in this newfound poverty, he found a degree zero of his cinema. It’s hard to compose a 5.1 soundtrack, as he had done for The Image Book, when all you are apt to do is lay indications on a piece of paper. So he had no other option but to do away with every last effect, every last excess, and stick only to the utmost necessary. He “looked for poverty in language”: tired, sick, his days numbered, that’s when he found it.

… my prolonged childhood made me an old age and that’s what I took for my freedom. — Raymond Queneau, Odile

Why Odile? Because Odile was his mother’s name. Mother Anna Magnani runs for her son and drops dead in the middle of the street. Why this lengthy excerpt from Bande à part, a movie that was far from what Godard considered his best? Because these two men shooting at each other, who look like the same man shooting at himself in the mirror, are the perfect image of the adult who spends his life running away from his childhood and who, just before dying, sees the face of his mother: “Arthur’s last thought was dedicated to the face of Odile.”

Why these masks underneath which we see nothing but a black void? Maybe adulthood is just the act of moving from one mask to another, always taking for granted that the real you remains untouched beneath them. But you are afraid to take them off. “Il y a en vous quelque chose d’affreux,” Odile says. There’s something horrible in you.

Why Odile? Because Odile is the anti-Nadja, the anti-Albertine, the anti-Anna Karina crying in a close-up. Because the novel is called Odile, but Odile herself is only present for one-tenth of its duration. Because we never get a description of Odile: neither her face, nor her body, nor her behavior. Because no one persecutes Odile, tries to decipher Odile, uses Odile as proof for their theories (as Breton did with Nadja). Because no one abandons Odile to die in a sanatorium. No one locks Odile inside their bourgeois mansion (as little Marcel does with Albertine). Who is Odile? She is there, then she isn’t. That is all.

But Odile is also a mother, his mother: faced with death, the old man gazes back upon his childhood. The picture of his face we see at the beginning of Scénarios bears a striking resemblance to the pictures he painted as a teenager: same colors, same thick, short lines, but now they lie on top of his face. Another mask? No. The old man, faced with impending death, realized he had taken a long detour only to arrive at the point where he started. The old man ran into the child. And he saw Odile’s face. Have we seen Odile’s face? I don’t believe I have. What do we know about Odile? Odile is the name we read at the cover: the face is not for us to see.

A whole life of agitation, and at the end you look at yourself in the mirror and see, at the place where should be a face, broken remains of masks. You look into yourself trying to see what’s behind them, and all you find is a black void. Your whole life you believed you were impossibly deep — took it for granted, in fact — and when the time came and you wanted to find out what lay at the bottom of your ocean, you touched the water to see how cold it was and were shocked to discover that it was as shallow as a pond. When you looked at your face in the mirror, you saw “nothing in your eyes”.[1] So you painted something on top of it. Your true face: an image of your childhood. “Behind the row of hotel yellers and of porters delirious with impatience, I saw Odile waiting for me.”

[1]From Godard’s last interview with Mediapart.

Comments are closed.