Jay Kelly

A former editor-in-chief of mine once told me to write lightly about heavy matters, and heavily about light ones — an adage that easily applies to Noah Baumbach’s and Emily Mortimer’s remarkable screenplay for Jay Kelly. On paper, Baumbach’s thirteenth feature, about the end-of-career crisis of the titular aging movie star (George Clooney, in a brazenly self-referential role), may sound trite. The resulting film, however, is anything but. Baumbach has managed to follow up his strained Don DeLillo adaptation White Noise (2022) with a wondrous bit of movie magic — a remarkably earnest dramatic comedy full of existential crises that constantly sparkles due to its playful grace notes.

Fittingly, the plot kicks off with a taste of real movie magic. Baumbach grants us a peek behind the Hollywood curtain, flexing a sweeping oner to present the film set as the stage for a polyphonic symphony of wildly differing characters that somehow manage to cooperate in lieu of assembling a film. All the oscillating crew members in this delicate constellation gradually make way for the real star: magnetic film icon Jay Kelly, who is one take away of the picture lock for what might be his final film. Expiration is suddenly on his mind now, with graying hairs and film festival invites for lifetime achievement awards as ominous warnings of the beginning of the end. Perhaps that’s why Kelly, a divorced dad of two grown-up daughters, starts to gravitate toward his family. Understandably, though, they have zero emotional need for a man who, in the past 35 years, has constantly chosen his career over intimate familial relationships.

The double whammy of his youngest daughter flying off on an Eurotrip for the summer, plus the passing of a filmmaker who served as Kelly’s surrogate father, fuels a sudden desire to break out of his pillowy prison of luxury and artifice. Coming awkwardly close to parental stalking, Kelly retraces his daughter’s itinerary, dragging his manager Ron (a brilliant Adam Sandler, in one of his all-too-rare dramatic roles), plus the rest of his sizable professional entourage, along for an adventurous road trip from Paris to Tuscany. All this sudden flux allows Baumbach to carefully dissect the tormented psyche of an actor in his desperate attempt to feel human again. “How can I play people,” Kelly muses after a series of hilarious interactions with the plebs in a train wagon, “when I don’t see people; don’t touch people.”

From this point on, Jay Kelly mostly alternates between two types of scenes. Humorous chance encounters with ordinary people rekindle Kelly’s sense of humanity, while the more fantastical side of things finds the aging star veering off in key memories that shaped his life and career. You can feel that Baumbach has a couple of new tricks up his sleeve after sculpting the fugue-like narrative of White Noise, specifically in the fluid ways he lets Clooney step into scenes of his past, as if he’s the audience of his previous life that unfolds like a farcical play. The looming anxiety of an aging, lonely man who struggles with past guilt is extremely palpable here, and it shouldn’t be too much to state that Jay Kelly represents a singularly high point in Clooney’s career — one that in the last decade or so has been plagued by Nespresso commercials and diminishing returns in more serious cinema fare.

What mostly shines through in Baumbach’s film, however, is the emotionally charged dynamic between Clooney and Sandler. The fraught bond between Kelly and Ron, who have built an ostensible friendship from a purely transactional relationship, turns out to be the central site of tension in Jay Kelly. With films like Greenberg and The Meyerowitz Stories, Baumbach has proven how deftly he can explore the porous nature of social connection. Here, he applies all that emotional discomfort to a larger-than-life celebrity who, over the course of the film, is painstakingly dragged back to the realm of ordinary human living. Jay Kelly is surprisingly moving in exploration of all the sacrifices Ron has made in private to keep Kelly’s stardom afloat, and the staggering amount of familial and relationship drama that Ron and others have had to endure, beyond Kelly’s knowledge, illustrates a keen understanding of social and relational complexity that proves foundational to the film’s larger layers of drama.

And then, in a cheeky bit of meta self-referentiality, Baumbach grants us a bit more movie magic. When Kelly finally does accept a lifetime achievement award, the montage reel during the ceremony consists entirely of snippets of Clooney’s earlier acting work. It’s a tremendous joke in itself, one that also hints at how much Clooney has mined his own life to inhabit this tragic character. That Baumbach, Clooney, Sandler, et al. have managed to squeeze so much comedic gold and genuine pathos out of such an existential, and arguably personal, downer only illustrates what a wondrously strange picture Jay Kelly is. — HUGO EMMERZAEL

The Wizard of the Kremlin

More than three years after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and over a decade after the annexation of Crimea, a desire to put the inner-mechanics of the Kremlin within a more human framework only feels natural. As in the aftermath of cascading geopolitical crises that shattered our grip on reality in front of our very eyes, a pressing question has emerged: how the hell did we even get here? And who is responsible for all this misery?

Although many astute books — from The Return of the Russian Leviathan by Russian author Sergei Medvedev to The Russo-Ukrainian War by Ukrainian scholar Serhii Plokhy — have been written about Russia’s war-mongering and the myriad ways in which the post-Soviet agents of power have hollowed out its empire from the inside, few of them have tried to put a human face on these architects of oppression. It’s exactly this that Giuliano da Empoli tried to combat with The Wizard of the Kremlin (2022), in which the Swiss-Italian author took a novelistic approach to the past three decades of Russian politics. Told from the personal perspective of Vladimir Putin’s fictional advisor Vadim Baranov, a presumed stand-in for the real-life shadowfigure Vladislav Surkov, da Empoli’s book attempts to frame Russia’s recent history through the anecdotal. This narrative framing device suggests a highly subjective vantage point, allowing for a compelling emotional history of Russia’s post-Soviet trajectory. Critics, however, have also remarked how this literary conceit too neatly fits within preexisting notions and conceptions about Putin and modern Russia, essentially resulting in a glossy do-over.

Now, we have Olivier Assayas’ remarkably faithful adaptation of that book, starring Paul Dano as Baranov and Jude Law as his “Czar” Vladimir Putin. Assayas’ The Wizard of the Kremlin could have been a scintillating political thriller that gives a human face to a despot and the Machiavellian advisor who engineered his political rise. Instead, Assayas’ 19th feature film is an impotent work that lands in the bottom tier of the prolific auteur’s oeuvre. This is particularly painful, as Assayas was once one of the most adept filmmakers to reflect on the flux of the 21st century as it unfolded in real-time. Demonlover (2001) — rightly championed by Jake Tropila on this very platform — managed to capture that lighting-in-a-bottle-moment in which the Internet took over our very fabric of existence, channeling the violence of a newly imposed hyperreality in a densely layered corporate thriller. The director’s miniseries Carlos (2010), meanwhile, was an electrifying study of Venezuelan terrorist Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, turning the political rebel into a bona fide rockstar through the splashy sensibilities of its director. And in turn, Personal Shopper (2016) managed to convey the haunting void of our late-capitalist social media era through a surprisingly spooky postmodern ghost story.

None of those auteurist interventions can be found in the straightforward handling of da Empoli’s book, which is strange, considering the novel’s narration entirely rests on the personal anecdotes of Baranov. Recounting his political ascension after the fall of the Soviet Union to an American journalist (Jeffrey Wright) specializing in Russian politics and literature, the film all too neatly covers the basics of Russia’s recent trajectory. In that process, any form of subjectivity is thrown out of the window, resulting in a series of flaccid scenes that amount to little more than Wikipedia-coded, matter-of-fact accounts of the fictionalized events that propelled a KGB agent from Saint Petersburg to the despotic reign of the Russian Federation. In particular, the lifeless cinematic treatment of the material disappoints on an individual scene level, as there is no visual hierarchy to speak of, nor any rhetorical positionality from Assayas. Dano and Law can try all they want to embody the opportunism and cynical villainy of these menacing figures, but their talking heads-esque handling of dialogue on cheap-looking set pieces makes no room for suspense or friction.

That’s a shame, as the ever-shifting cultural backdrops against which they operate are endlessly fascinating. Particularly, the turbulent early years of post-soviet Russia, with its crippling poverty, unchecked violence, criminal corruption, and flourishing anti-establishment cultural scenes are grossly mishandled here. Assayas still tries to flex his rock sensibilities by having Dano chew the scenery at anarchist punk parties and the champagne-fueled dancefloors of kitschy nightclubs, but due to a lacking art department, including subpar make-up and costume design, none of this ever hits the way it should. Simultaneously, the violent poverty of the era is entirely glossed over in Yorick Le Saux’s flattened cinematography that barely boasts any dynamic range to speak of. It makes one yearn for Adam Curtis’ brilliantly hauntological archival miniseries Russia 1985-1999: TraumaZone (2022), which burst from the seams with textural details of those scary and chaotic years.

You could say it’s almost radical to make a boring film about such an urgent political story, but such a meta-take would give too much credit to a director who here bafflingly seems to be operating as an unambitious gun for hire. Once The Wizard of the Kremlin moves closer to the present and drags the Chechen wars and the occupation of Ukraine into the narrative, the film’s ineptness only becomes more palpable. This is mostly to do with the flawed source material that offers a highly teleological and linear reading as to how Putin rose to power, resulting in a kind of cowardly confirmation bias. A better pairing of director and script would be able to convey the overwhelming momentum of history’s merciless march toward the future within the grain of the film. Assayas, however, has captured this daunting story through the prism of thoughtless mediocrity, leaving viewers with unfortunately little to do but yawn in the face of one of the gravest political tragedies of our times. — HUGO EMMERZAEL

How to Shoot a Ghost

Jessie Buckley’s hesitant recitation of Bonedog — the achingly painful poem written by Eva H.D. — is one of the most memorably harrowing sequences in Charlie Kaufman’s already memorably harrowing I’m Thinking of Ending Things. The actress’s flat, almost affectless vocal performance doesn’t match her very obviously depressed physical performance in the same way Kaufman’s deliberately jarring edits (emphasizing discontinuity) don’t match the brutally bruising clarity of Eva H.D.’s written words. What you get, then, is an emotionally gut-wrenching disjunct, with Buckley’s recitation and Kaufman’s direction pushing us away from her character’s despair but Buckley’s body language and Eva H.D.’s words pulling us straight back in. This tension — between form and content — deepens the crushing existential weight felt by Kaufman’s character(s); it leaves an emotional scar because Eva H.D.’s words manage to — perhaps only occasionally — pierce through Kaufman’s narrative and formal game of psychological (dis)associations in I’m Thinking of Ending Things.

The first short film that the two artists collaborated on after Kaufman’s most ambitiously directed feature film, “Jackals & Fireflies” (2023), is stripped of all this, well, “distracting” gamesmanship. And it’s entirely for the worse — Kaufman essentially fashions his version of sub-Malickian reverie in Jackals & Fireflies, producing an impressionist montage of New York City filtered through the bleary and blurry perspective of a nameless woman (played by Eva H.D.) whose poetic voiceover, constantly complemented by a twinkly background score, guides everything in the film. Whatever tension is there to be found between her caustic words (recited, here, somewhat affectlessly by Eva H.D. herself) and dreamy, soft-focused imagery is nullified by the constant use of the background score; there’s concerningly little else to note here other than the fact that Kaufman, along with cinematographer Chayse Irvin, shot this film entirely on a Samsung Galaxy S22 Ultra.

It’s best to keep your expectations similarly low for How to Shoot a Ghost, Kaufman’s second short collaboration with Eva H.D., which is making its premiere Out of Competition at the Venice International Film Festival this year. Jessie Buckley also reunites with the pair, prompting an (unfairly) misguided expectation on this writer’s part that this short will create (or, at least, recreate) the deeply distressing sense of dread that dominated each and every second of the Bonedog recitation sequence in I’m Thinking of Ending Things. But no. This is essentially Jackals & Fireflies — The Athens Edition, just not shot on a phone and not in the conventional widescreen aspect ratio. Its plot, loosely speaking, follows two newly dead people — one, a translator (Josef Akiki), and the other, a photographer (Jessie Buckley) — as they meet on the streets of Athens, a city in which, as described by Kaufman in his director’s statement for the film’s premiere, “the bones of history are always on display.” Archival footage of Athens’ turbulent political history collides with these characters’ (constantly exhausting) poetic musings — liltingly narrated by Eva H.D., Jessie Buckley, and Josef Akiki — as they try to make sense of their place and time after life.

Conceptually speaking, How to Shoot a Ghost offers a much more fertile playground for Kaufman to combine and collide form and content than Jackals and Fireflies did. The consistent intercutting and crossfading between past, present, and future — again, overly complemented by a generically mournful background score, most definitely to its detriment — employs a similar tension between formal disjunct and poetic harmony like the Bonedog sequence in I’m Thinking of Ending Things did. The idea — again, clearly expressed by Kaufman in the director’s statement — is to create a “liminal space” whereby everything is a blur for these ghosts, who feel entirely displaced from both place and time.

But unlike, say, Sans Soleil (1983), the monumental Chris Marker cine-essay that manages to create an unforgettably hypnotic blur out of a similarly constant barrage of voiceover and “banal” images, nothing about the compositions here, and their obvious rhyming with the perfunctorily poetic words in How to Shoot a Ghost, lingers. Athens’ history, much like the characters’ personal histories, is treated like a vague blur, reduced by Kaufman’s commitment to romantic poeticism, to grand gestures and flash(y) images that don’t so much swirl around in your head after you’ve watched the film, but rather just seem to evaporate into ether. It’s perhaps apt in a way that a film about the fleeting nature of socio-political histories and personal lives feels so slight, but, in a different — and more significant — sense, it’s immensely disappointing that How to Shoot a Ghost never manages to make those fleeting feelings feel, in any way, memorably elegiac. — DHRUV GOYAL

Orfeo

Filmmaker, artist, and animator Virgilio Villoresi’s first feature, Orfeo, made after years of directing short films, advertisements, and music videos, is a whimsical, finely crafted creation; a mélange of vintage techniques, its interweaving of countless literary and cinematic references forms a film that is inarguably a product of its director’s idiosyncratic interests. An adaptation of Dino Buzzati’s 1969 graphic novel Poema a fumetti, co-written by Villoresi and Alberto Fornari, Orfeo is a reworking of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth set in a highly stylized 1960s Milan and a labyrinthine underworld, and which consists of both stop-motion animation and live-action film. Despite the film’s somewhat overfamiliar story, Villoresi’s immaculate craftsmanship and the abundant visual flair he cultivates in each frame more than compensate for the minor narrative weakness.

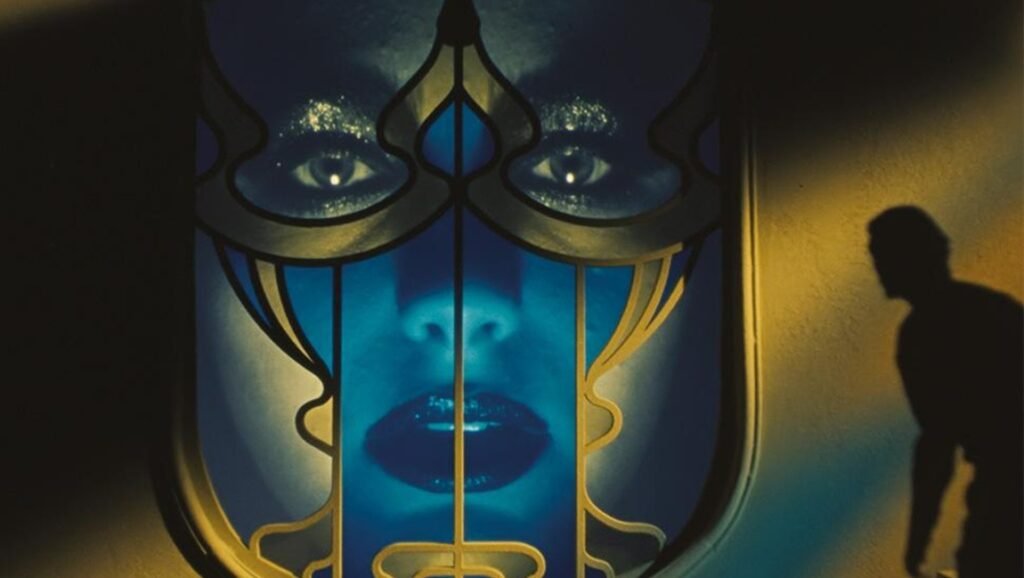

Orfeo (Luca Vergoni) is a lounge pianist at the club Polypus. On a stage framed by Beaux Arts wrought-iron ornamentation, he plays tantalizing arpeggiated tunes for a stylish audience, seated at club tables behind silver candelabras. He makes a connection with a beautiful, mysterious audience member named Eura (Giulia Maenza), and they fall into a love affair that culminates in a romantic night spent at Orfeo’s picturesque mountainside cabin. Eura disappears soon after without any explanation, but when Orfeo sees her ghostly form passing through an unassuming door, he learns that, to reunite with Eura, he must pass through this spectral door himself. Orfeo then embarks on a journey through the afterlife, where time and space do not correspond to the rhythms of the surface world, and where he encounters magical beings that give him a series of strange tasks so that he might be able to find Eura again.

Orfeo is fundamentally a by-the-books retelling of the Orpheus myth, where the lover follows his beloved into the afterlife, reunites with her, and then loses her to death once again just as he returns to the world of the living. Villoresi, who also edited the film, treats the mythical, metaphysical romance seriously, but it’s always evident that what interests him the most are the opportunities for technical play and experimentation. “It became an opportunity,” Villoresi noted in his director’s statement for the film’s premiere out of competition at the Venice Film Festival, “for me to blend languages cultivated over time — including artisanal animation, experimental cinema, and optical techniques — into a symbolic and sensorial tale.”

The live-action sequences are shot in a studio, where Orfeo and Eura move through intricately decorated scenery conceived of by production designers Riccardo Carelli and Federica Locatelli. In the Milan scenes, establishing shots and interstitial scenes are largely animated in charming and detailed stop-motion (animations are credited to Anna Ciammitti, Stefania Demicheli, and Umberto Chiodi), but the ambition and imagination of the animation come to full fruition once Orfeo descends into the afterlife, where wild-eyed floating spirits, pirate skeletons, and a disembodied jacket are just a few of the characters who appear on Orfeo’s journey. The 16mm cinematography by director of photography Marco De Pasquale is both vivid and hazy throughout, creating an atmosphere of simultaneous vibrancy and mystery, with Angelo Trabace’s alternately playful and melancholic score providing an aural corollary.

While inarguably a sui generis work, it’s also a reference-heavy one. Beyond the obvious mythological inspirations, one can find echoes of Tim Burton and Henry Selick’s lightly Gothic stop-motion films, classic children’s story adaptations like The Wizard of Oz and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, eclectic entries from the European art cinema canon including Fellini’s Toby Dammit and Chris Marker’s La Jetée, and Roger Corman’s vibrantly colored Edgar Allan Poe adaptations — and this is far from an exhaustive list. The main drawback to Villoresi’s liberal interpolation of cinematic and literary references is that it sometimes prevents Orfeo from standing on its own, instead rendering it overly indebted to an existing canon. For the most part, though, Villoresi’s conversation with inspirational works is a fruitful one, creating links to the film’s artistic forbears and incorporating each in such a way that is utterly distinct to the filmmaker.

Orfeo, on the whole, evinces a refreshing sense of lighthearted experimentation bolstered by seasoned craftsmanship. This is ultimately what is most satisfying about the film; the combination of artistic spontaneity and practical precision is a rare one, and creates an experience that feels both playful and solidly constructed. If the central romance feels a bit thin in comparison to the lavish attentions paid to the mise en scène, it’s forgivable, as Villoresi’s bold sense of invention and imagination are what truly propel the film forward and linger after its conclusion. — ROBERT STINNER

Comments are closed.